I remember the Sundays of my childhood vividly.

In my conservative Catholic community, the routine was as predictable as the rising sun. You dress up. You go to Mass. You stand when told to stand, kneel when told to kneel, and recite the prayers you memorized before you could even comprehend them.

It was a world of perfect order. If you had a question, there was a Catechism answer. If you had a problem, there was a specific prayer. God was, in many ways, presented like a cosmic vending machine: insert the right coins (sacraments, obedience, attendance), and receive the product (salvation, blessing, peace).

But as I grew older, I could not help but feel a gnawing emptiness beneath the ritual.

I looked around at the “faithful”—people who would gossip viciously about “outsiders” in the church parking lot, or the priest who seemed more concerned with the bureaucracy of the parish than the suffering of the human heart.

It felt like a performance. It felt like everyone was sleepwalking.

The turning point came when I stepped out of that bubble – into the real world. I began meeting the so-called “outsiders”—people my community warned me about (i.e. the non-Catholics; people from other regions/ cultures). Ironically, I found that they were humans, often much deeper and more compassionate than the “righteous” people back home.

At the same time, I also, gradually, discovered a burning interest in the “big questions“—the meaning of life, the nature of suffering, and why we are here.

The “checklist” religion of my childhood suddenly felt too small to hold these massive questions. I decided that I needed something real.

That was the starting point of my dive into philosophy – specifically, into Existentialism.

As I went deeper, I could not help but realize that there are a lot of misconceptions about this school of thought. For example, I recently came across a Reddit thread where a user raised a question like this:

“I don’t understand Christian Existentialism. The Bible gives us all the answers: Why we exist (God created us), what to do (obey commands), and where we go (Heaven/Hell). So why struggle? Why make it complicated?”

On the surface, the arguments seem to be right. If religion is just a checklist, there is no struggle.

But for the Seeker—for the person who has looked at the suffering in the world, the absurdity of life, and the complexity of humanity—the checklist isn’t enough.

We don’t just want to know about God; we want to experience the Ultimate Reality.

We don’t want a “System” that explains away our pain; we want a Presence that can endure it with us.

If you have ever sat in a pew and felt alone, or if you have ever felt that your doubts made you a “bad” believer, then I believe we can call ourselves “pals”.

In this article, I’m going to share some of my own perspectives on Christian Existentialism. To me, it is not a heresy – but simply the radical belief that God is not found “out there” – in comfortable theories, but “in here” – in our own hearts.

Highlights

- Christian Existentialism argues that God is not a checklist of rules or a “vending machine” for blessings, but a Relationship to be experienced subjectively.

- Unlike traditional dogma which fears uncertainty, this philosophy views doubt and anxiety (“Angst”) as essential signs that we are truly awake and spiritually alive.

- Logic is not enough for the seekers treading the path. Bridging the gap to the Divine requires a terrifying, irrational “leap” of trust—like Abraham, or Indiana Jones stepping into the abyss.

- True faith isn’t just believing the right things; it is the active choice to love unconditionally (the “Walk of Love”), even when the world seems absurd or unfair.

What is Christian Existentialism?

At its core, Christian Existentialism is a revolt against “The System.” It is a theo-philosophical movement that emphasizes the individual’s subjective relationship with God over objective religious doctrines. One of its main tenets is that faith is not a matter of intellectual assent to a set of rules, but a personal choice to follow God in an uncertain world.

Where does this school of thought come from then?

In the 19th century, philosophers like Hegel and Kant were trying to build massive, logical systems to explain God and the Universe. They treated history like a math equation.

Then came the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard – widely considered the father of existentialism – who essentially said: “That’s all very nice, but it doesn’t help me when I’m anxious, grieving, or dying.” In his effort to resolve this problem, he introduced the concept of Subjectivity.

Now, don’t let that word scare you. In promoting the idea of Subjectivity, Kierkegaard didn’t mean that truth is “relative” – or that you can make up your own facts. What he meant is that spiritual truth only becomes “true” when you live it.

Think of it this way: You can study a map of Paris (Objective Truth). You can memorize the street names and the history. But that is fundamentally different from actually walking the streets of Paris, smelling the bread, and feeling the rain on your face (Subjective Truth).

Christian Existentialism, as proposed by Kierkegaard (and later thinkers such as Gabriel Marcel, Paul Tillich, John Macquarrie, etc.), argues that the Bible isn’t a map to be memorized; it is a street to be walked.

Christian existentialist philosophers

(Image source: Wikimedia)

The Roots of Christian Existentialism

While the label is modern, the “vibe” of Christian existentialism dates back centuries ago.

- We see it in the book of Ecclesiastes, where the writer screams into the void, “Meaningless! Meaningless! Everything is meaningless!” He doesn’t sugarcoat the absurdity of life; he confronts it head-on.

- We see it in the work of St. Augustine, who wrote, “Our hearts are restless until they rest in Thee.” That restlessness—that angst—is the engine of existentialism.

- We see it, paradoxically, even in the systematic theology of Thomas Aquinas, in his insistence that the existence of God must first be established through reason and experience (his Five Ways), rather than simply taken as a starting point. To a certain extent, this foundational need for a personal, intellectual leap mirrors the existential project.

- We see it in the moral dilemmas faced by characters in Dostoevsky’s novels (e.g. Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment). Most of his works wrestle intensely with freedom, guilt, and the necessity of suffering for redemption.

- We also see it in the religious mystics (e.g. think of those like Meister Eckhart, St. John of the Cross, or the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing) and the “God above God” described by theologian Paul Tillich. According to Tillich, our tendency is to turn God into an idol—a “being” who lives in the sky and manages the universe. But the true God is the ground of all being.

Christian Existentialism vs Atheistic Existentialism

So, how does this movement differ from the mainstream Atheistic Existentialism promoted by thinkers such as Sartre and Camus? (for the sake of simplicity, I’m including Camus here too – because he tackled the same questions as Sartre, even though he did not identify as an existentialist)

Generally speaking, both groups agree on the starting point: We are free, and life is often absurd.

If we look at the world honestly, we see suffering that makes no sense. We see absurdities everywhere. How can the existence of an omnipotent God – or a cosmic order – be justified then?

Both the Christian and the Atheist Existentialist refuse to ignore this undeniable reality. They both reject the “easy answers” of society.

However, the differences lie in their response to that silence.

The source of meaning

- The Atheist

Since the universe has no inherent meaning, you are entirely alone. You are the architect of your own reality – and it is your job to create your own values from scratch. To quote Sartre:

Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.

- The Christian

You are free, and yet you are NOT alone. Rather than being created by you, meaning is discovered by you through a relationship with the Infinite – a Presence humanity cannot fully understand.

The view of Anxiety (Angst)

- The Atheist

Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom—a result of the realization that you alone are accountable for everything. You cannot make excuses or blame anyone; attributing your own actions to people or society (e.g. ‘I know it’s not good, but it’s because my boss told me to do so‘) is just a sign of bad faith.

- The Christian

Anxiety stems from the tension between our finite bodies (which die) and our infinite souls (which long for God). We feel anxious – because we are citizens of two worlds.

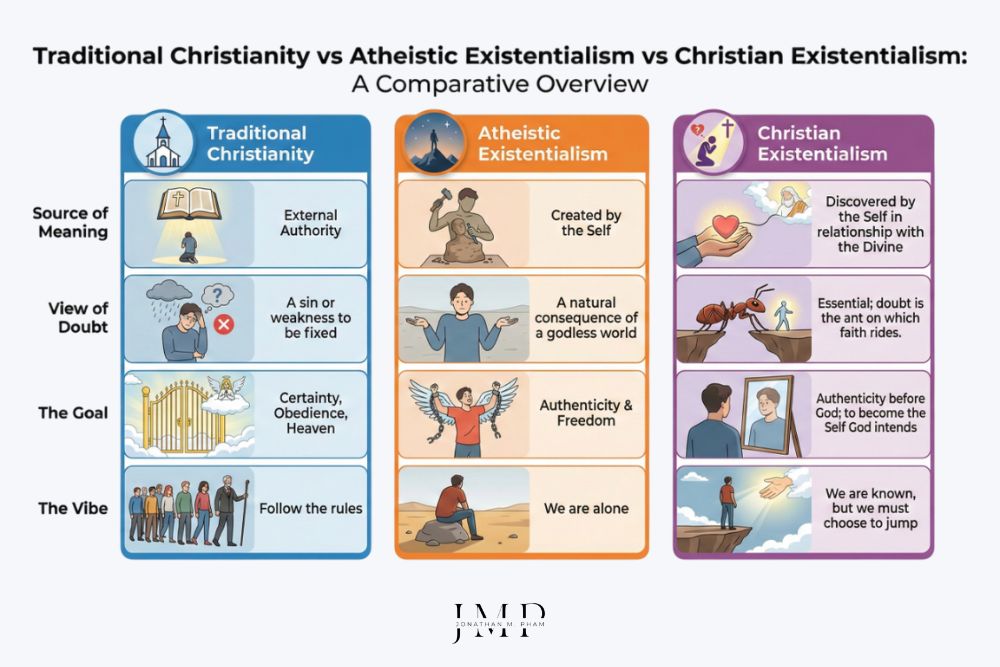

Here is a quick breakdown to help you better visualize how the two approaches differ from traditional religions (specifically, Christianity) and from each other.

| Feature | Traditional Christianity | Atheistic Existentialism | Christian Existentialism |

| Source of Meaning | External Authority (Church/Bible) | Created by the Self | Discovered by the Self in relationship with the Divine |

| View of Doubt | A sin or weakness to be fixed | A natural consequence of a godless world | Essential. “Doubt is the ant on which faith rides.” |

| The Goal | Certainty, Obedience, Heaven | Authenticity & Freedom | Authenticity before God. To become the “Self” God intends |

| The “Vibe” | “Follow the rules.” | “We are alone.” | “We are known, but we must choose to jump.” |

Christian existentialism vs atheistic existentialism

All in all, to the Christian Existentialist, the fact that the universe is silent doesn’t mean God is dead. It means God is not a “fact” to be proven by science or logic – but a Relationship to be chosen.

And that choice requires something terrifying – which we will discuss in the following section.

The Leap of Faith: The Core Tenet of Christian Existentialism

So, if God is not a “fact” to be proven with a textbook, how do you reach Him?

Here is Kierkegaard’s answer – which has now become a cornerstone of Christian existentialism: we must take a leap of faith.

Logic can take you to the edge of the cliff. It can tell you that the universe is vast, that humans crave meaning, and that “something” might be out there. But it cannot build a bridge to the other side.

Between you and the Divine, there is a gap of “Objective Uncertainty.”

To cross it, walking is not an option. You have to jump.

At the point where the road swings off (and where that is cannot be stated objectively, since it is precisely subjectivity), objective knowledge is suspended. Objectively he then has only uncertainty, but this is precisely what intensifies the infinite passion of inwardness, and truth is precisely the daring venture of choosing the objective uncertainty with the passion of the infinite.

Søren Kierkegaard

The Knight of Faith

To illustrate his own philosophy, Kierkegaard pointed to the Biblical story of Abraham and Isaac. In the story, God asked Abraham to sacrifice his son, Isaac – a command that made no sense. Unethical. Cruel. And worse, it contradicted God’s previous promises to Abraham. (that he would make Abraham the father of a multitude of nations – and that his descendants would be innumerable as the stars in the sky)

Some time later God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!”

“Here I am,” he replied.

“Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac—and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on a mountain I will show you.”

Genesis 22:1-2

A rational person would say, “This is crazy, I won’t do it.”

But Abraham obeyed God’s command without questioning—not because he was a murderer, but because he trusted God more than his own understanding of ethics. He believed, by virtue of “The Absurd,” that he would get Isaac back.

Kierkegaard called this act an example of the “Knight of Faith“. It is the ability to float in the deep water of uncertainty, trusting that you will float, even when every rational bone in your body says you will drown.

A leap from the lion’s head

If you find the story of Abraham too ancient or heavy, let me share with you a more personal example.

Back in the day, when I was a teenager – ignorant of philosophy but hungry for adventure – I was exposed to the concept of the “leap of faith” for the first time when I watched the movie Indiana Jones & the Last Crusade.

At the climax of the story is a truly haunting scene for me – where the protagonist Indy stands at the edge of a massive chasm, and is instructed that he must take a “leap of faith.” He looks down into the abyss. There is no bridge. No rope. Just open air.

But his father is dying behind. He has to choose.

He closes his eyes, puts a hand over his heart, and steps out into the “nothingness”. And in that moment—clunk—his foot lands on a bridge that was invisible from where he stood.

To me, that scene is a perfect visualization of the Christian Existentialist experience. You don’t step out because you see the bridge. You step out because you trust the bridge is there, even when your eyes tell you otherwise.

The Sickness Unto Death

According to Kierkegaard, humanity is free to make a choice. To either make the leap we have discussed, or to refuse to do so. If they go with the latter option, they will fall victim to what Kierkegaard called the “Sickness Unto Death” (or in simpler terms, Despair).

More than mere sadness, despair is the refusal to be who you are. It happens when you stand at the edge of the chasm, see the adventure, and choose to stay safe in the cave because you are afraid.

In other words, it is knowing the truth but refusing to live it.

To see the possibility of a deeper, more holistic and meaningful existence, yet remain stuck because of the need for certainty – that itself is a tragedy. Something that I sometimes refer to using this humorous scriptural twist:

“Woe to those who have seen – and yet have not believed.”

The three Stages of Life’s Way

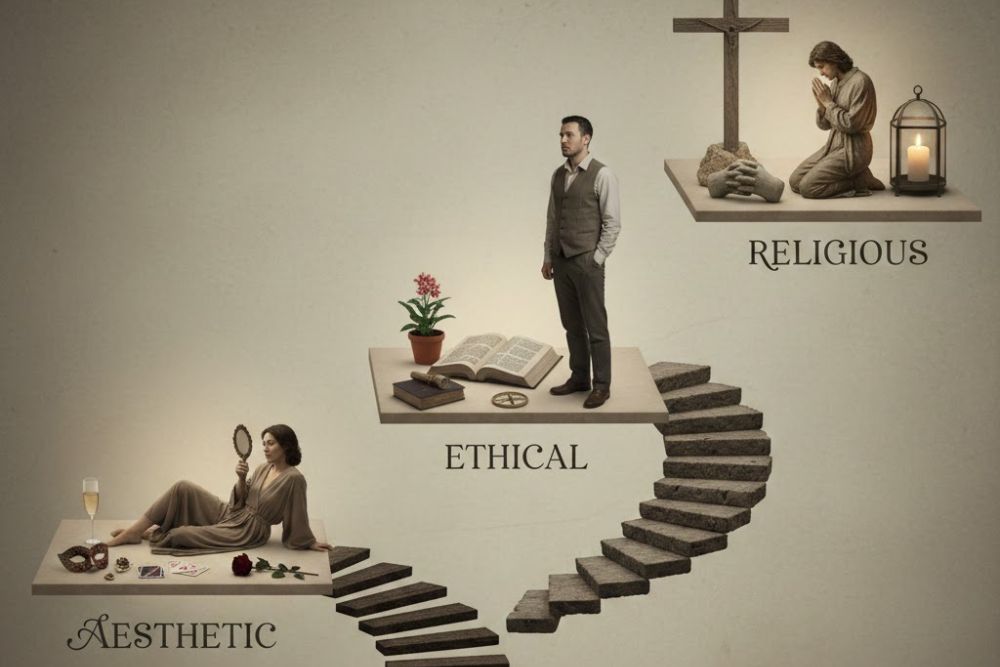

The leap of faith is not a choice made in a vacuum; it is the final, decisive move in what Kierkegaard saw as the individual’s journey through the Three Stages of Existence (or “Spheres of Life”). Every person lives primarily within one of these three stages, though the transition between them is never automatic—it always requires a conscious, passionate choice.

- The Aesthetic Stage 🎭

The first one is the life of immediate gratification and the pursuit of pleasure, novelty, and sensory experience. The aesthete lives moment-to-moment, avoiding commitment and responsibility. The highest good is enjoyment; the lowest is boredom.

This is the stage of the playful seducer or the unreflective pleasure-seeker, whose life ultimately lacks continuity and deeper meaning, leading eventually to despair—which you already know is the “Sickness Unto Death.”

- The Ethical Stage 🏛️

To escape the despair of the aesthetic life, one makes a leap into the ethical. Here, the individual commits to universal, rational moral laws and duties—to society, family, and self. The ethical person chooses a coherent, responsible self, dedicated to living by a consistent moral code. This is the realm of the good citizen or the dedicated professional.

However, this stage is still limited, as the reliance on rationality and universal duty cannot account for the radical, personal, and sometimes contradictory demands of the Divine. The ethical life, while necessary, may still lead to a new form of despair when faced with the absolute nature of sin and human finitude.

- The Religious Stage ✨

The final, and highest, stage is the religious, exemplified by the Knight of Faith, like Abraham. To enter this stage, one must recognize the limits of the universal ethical law and make the ultimate Leap of Faith—a choice based not on reason or proof, but on an infinite, subjective passion and a direct, singular relationship with the Absolute (God).

This is where the ethical is “teleologically suspended” for the sake of the divine command, embracing the Absurd and the Objective Uncertainty discussed earlier. It is only in this stage, through the paradox of faith, that the individual fully realizes their authentic self and truly overcomes despair.

Read more: Are You Living or Just Existing? Let’s Find Out!

East Meets West: My Personal Experience as a Christian Existentialist

For my part, I identify as a Christian Existentialist, but I often add an asterisk to that label.

While my roots are in the Christian tradition, my branches – over time – have grown toward the East. Specifically, I find deep resonance in Buddhism, Zen, and the concept of Dao.

To some traditionalists, my choice might sound like a contradiction. Yet to me, it feels like the only honest way to view the Infinite.

The death of the Idol

Nietzsche once said, “God is dead.” As far as I know, many conventional Christians tend to shudder at his statement – viewing it as a sign of nihilism, atheism, or anti-Christianity.

However, I believe there is some profound spiritual truth here.

Sometimes, God needs to die.

The “God” that needs to die is the rigid, Westernized, man-in-the-sky idol we have created. The God who is merely a projection of our own cultural rules.

That God must die so that the True God—the Ultimate Reality—can be reborn in our hearts.

In the Western world, God is often portrayed using a strict “Father-figure” imagery. (which I find hard to embrace) A very exclusive God who enforces rules ruthlessly – whose followers frequently adopt an “us vs them” mentality, are quick to judge, and are not hesitant to dismiss other religions/ ideologies as “heresies”/ “roads to Hell”.

For my part, I believe in a God who is also Mother-like – a God who does not sit on a cloud judging us, but who descends into the mud to suffer with us.

The God of Silence

It is the God depicted in Shusaku Endo’s masterpiece novel Silence. (which has been adapted into a movie with the same name by director Martin Scorsese) For those who are not yet familiar with the story, it follows a Jesuit priest named Rodrigues, who embarked on a missionary journey to 17th-century Japan. He expected God to be a figure of power and glory – who would strike down the torturers persecuting Christians.

But God did nothing. The heavens were silent. And his believers were dying – seemingly for nothing.

In the climax of the story, Rodrigues was forced to trample on a fumie (a bronze image of Christ) to save Japanese peasants from torture. He expected the image to judge him. Instead, what he heard was something else:

“Trample! It was to be trampled on by men that I was born into this world. It was to share men’s pain that I carried my cross.”

To me, this is the God of Christian Existentialism.

Not the distant Judge, but the Suffering Companion who accepts our brokenness to be with us. One who shares similarities with the Eastern idea of the Bodhisattva—an enlightened being who delays their own liberation to suffer with the people.

One whose concern is NOT to prove his own righteousness, but to alleviate humanity’s suffering.

One who engages not in an I-It relationship—viewing humans as merely tools or subjects to be ruled—but in an I-Thou relationship, where deep connection happens.

One who is willing to tread a Middle Path—and, shockingly, to be changed as a result of that relationship.

If I let myself really understand another person, I might be changed by that understanding. And we all fear change. So as I say, it is not an easy thing to permit oneself to understand an individual.

Carl Rogers

Christian existential crisis & questions

Going beyond the label

This may sound a little awkward, but many times, I find myself wondering: Do secular existentialists like Sartre really not believe in God? Or do they just reject the caricature of God that religion has sold them?

As an example, Simone de Beauvoir once admitted:

I am incapable of conceiving infinity, and yet I do not accept finity. I want this adventure that is the context of my life to go on without end.

And Camus once wrote:

In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger – something better, pushing right back.

If I have to say something about the above-mentioned reflections, it’s this: those secular philosophers were expressing a longing for the Infinite. In their own way, they were somehow touching the Divine spark within them. (in fact, I dare to say that Camus’s “Sisyphus”—who keeps pushing the rock despite knowing it will roll back down—is a model for the Saint who keeps loving a broken world)

Somehow, thinking about it makes me recall the words of Martin Buber (a Jewish existentialist):

“The atheist staring from his attic window is often nearer to God than the believer caught up in his own false image of God.”

At the end of the day, labels like “Christian” or “Existentialist” or “Buddhist” are just fingers pointing at the moon. They are NOT the moon itself.

The goal is not to wear the right badge; the goal is to know the Truth.

As I – an East Asian myself – have learned from my life, sometimes the best way to know the Truth is not to conquer it with logic, but to sit with it in silence.

If any man can convince me and bring home to me that I do not think or act aright, gladly will I change; for I search after truth, by which man never yet was harmed. But he is harmed who abideth on still in his deception and ignorance.

Marcus Aurelius

How to Be a Christian Existentialist: Living the “Absurd” Grace

As I have figured, finding the truth in silence is one thing. However, living it out in a noisy, demanding world is another.

This brings us to the most practical question of all: How do we actually live this way?

The Absurdity of Grace

For my part, I believe we can find the answer by looking to one of the most existential stories ever told in the Bible: The Parable of the Workers in the Vineyard. (for those of you who are non-Christians, here is the whole story told in the Gospel of Matthew)

The kingdom of heaven is like a landowner who went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard. After agreeing with the laborers for a denarius for the day, he sent them into his vineyard.

When he went out about 9 o’clock, he saw others standing idle in the marketplace, and he said to them, ‘You also go into the vineyard, and I will pay you whatever is right.’ So they went.

When he went out again about noon and about 3 o’clock, he did the same.

And about 5 o’clock he went out and found others standing around, and he said to them, ‘Why are you standing here idle all day?’

They said to him, ‘Because no one has hired us.’

He said to them, ‘You also go into the vineyard.’

When evening came, the owner of the vineyard said to his manager, ‘Call the laborers and give them their pay, beginning with the last and then going to the first.’

When those hired about 5 o’clock came, each of them received a denarius. Now when the first came, they thought they would receive more; but each of them also received a denarius.

When they received it, they grumbled against the landowner, saying, ‘These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.’

But he replied to one of them, ‘Friend, I am doing you no wrong; did you not agree with me for a denarius? Take what belongs to you and go; I choose to give to this last the same as I give to you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or are you envious because I am generous?’

I suppose if we interpret it from a conventional perspective, the parable makes absolutely no sense at all. Clearly, the early workers were right, weren’t they? More Work = More Pay – that’s just logic, “common sense”.

But the Landowner (God) rejects the system entirely. He says, “Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me?“

This, to me, is the Absurdity of Grace.

To the Christian Existentialist, life is not about being a “good person” or following the rules just to get a “paycheck” (a certificate of salvation or public recognition). What matters is NOT working harder to earn merit, but ACCEPTING reality as it is—accepting that Love is a gift, not a transaction—even when it doesn’t make sense to your rational mind.

Faith as action

Faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead.

James 2:17

That being said, accepting doesn’t mean sitting on the couch doing nothing.

If we take a look back at the parable, the workers hired at the 11th hour still went into the vineyard. They didn’t just say, “I believe in the Landowner.” They responded to the call. They moved.

In other words, the “Leap of Faith” must be followed by the “Walk of Love.”

It is choosing to love unconditionally, not for a reward (since the reward is the same for everyone), but because it is WHO YOU ARE – deep down.

It is serving others, not to earn “brownie points” with God, but to manifest the reality of the Kingdom in the here and now.

It is a personal commitment—a daily leap—to prioritize Relationship over Rules.

The coming of the kingdom of God is not something that can be observed, nor will people say, ‘Here it is,’ or ‘There it is,’ because the kingdom of God is in your midst.

Luke 17:20-21

The Universal Vineyard

You do not need to be baptized to hear the call of the Vineyard.

- The Christian calls it the Holy Spirit whispering in the heart.

- The Buddhist calls it Buddha-nature—the seed of enlightenment that exists in all beings.

- The Hindu calls it Atman—the Divine spark within.

- The Confucian philosopher Mencius once said, “Men at birth are naturally good” (人之初,性本善), referring to the innate “sprouts of virtue” we all possess.

Whatever you call it, the experience is the same. It is that nagging pull in your chest that tells you to help the stranger, to forgive the enemy, or to speak the truth when it would be easier to stay silent.

When a secular doctor flies into a war zone to save lives, expecting nothing in return, she is in the Vineyard.

When a Buddhist monk sits in compassion for the suffering of the world, he is in the Vineyard.

They are, essentially, responding to the Ultimate Reality of Love – regardless of the label they wear.

When two people relate to each other authentically and humanly, God is the electricity that surges between them.

Martin Buber

FAQs

For those trying to piece this all together, here are a few common questions I often hear.

What are the core beliefs of Christian Existentialism?

If we had to boil it down, the core tenets include:

- Subjectivity: Truth must be lived/experienced, not just memorized.

- The Leap of Faith: God cannot be proven by logic; He must be chosen through a risk of trust.

- Angst (Anxiety): Anxiety is not a sin; it is the natural dizziness of being free.

- Authenticity: The greatest sin is “The Sickness Unto Death“—conforming to the crowd rather than being your true self before God.

Is Christian Existentialism unbiblical?

Not at all, from my own perspective. While it does challenge religious tradition, it is deeply rooted in scripture.

The book of Ecclesiastes is pure existentialism (“Everything is meaningless“).

The cries of Job, the doubts of the disciple Thomas, and the “foolishness of the Cross” (1 Corinthians) – all of them align with existential thought.

Trivia: In case you did not know, the word “existentialism” was originally invented by a Christian – specifically, the Catholic philosopher Gabriel Marcel, who came up with it to distinguish his theistic view from Sartre’s atheistic one. Initially, Sartre rejected the label, but later – due to the public’s growing obsession with it – decided to embrace and rebrand it.

In other words, what is now widely considered an “atheistic” philosophy actually has deep roots in religious thoughts. So to deem it as “unbiblical” or incompatible with Christianity is… well, I might say, an oversight.

Can I be a Christian Absurdist?

Yes. In fact, the Cross is the ultimate symbol of the Absurd—God dying for humanity makes no logical sense. A Christian Absurdist embraces the paradoxes of faith (God is human, life is death, power is weakness) and chooses to live with passion despite the lack of logical answers.

Further Resources for the Seeker

If you would like to dive deeper into these waters, here are a few works that have shaped my own journey.

Christian Existentialism books to read

Check out my full list of recommended existentialism books here!

- Fear and Trembling by Søren Kierkegaard (The classic text on the Leap of Faith).

- The Sickness Unto Death by Søren Kierkegaard (A diagnosis of spiritual despair).

- The Courage to Be by Paul Tillich (Essential for understanding the concept of “God above God”).

- Silence by Shusaku Endo (A masterpiece on God suffering with humanity).

- I and Thou by Martin Buber (On finding God in interpersonal relationships).

Movies to watch

Below are just a few top picks; you can find out more good existential movies here!

- Silence (2016) – directed by Martin Scorsese.

- The Tree of Life (2011) – directed by Terrence Malick.

- The Seventh Seal (1957) – directed by Ingmar Bergman (A knight plays chess with Death—pure existentialism).

- First Reformed (2017) – directed by Paul Schrader.

Quotes to ponder

For those who are interested, feel free to check out more existential quotes here!

The man of faith who has never experienced doubt is not a man of faith.

Thomas Merton

Fanatics do not have faith – they have belief. With faith you let go. You trust. Whereas with belief you cling.

Yann Martel (Life of Pi)

Whatever you are is never enough; you must find a way to accept something, however small, from the other to make you whole.

Chinua Achebe

Christian existentialism explained

Final Thoughts: To Be a Flickering Light in the Darkness

We live in a time of great disruption. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is questioning what it means to be human. Global conflicts are shaking our sense of security. The “systems” we trusted—political, economic, religious—are showing their cracks.

But this is NOT a reason to despair. It is a call to action.

We are being invited to stop clinging to the “God of the Machine”—the idol of certainty and safety—and to embrace the God of Reality.

We are called to kindle a light in the darkness. As the philosopher Hannah Arendt once wrote:

“That even in the darkest of times we have the right to expect some illumination, and that such illumination might well come less from theories and concepts than from the uncertain, flickering, and often weak light that some men and women, in their lives and their works, will kindle…”

That kind of “light” does not always take the same form. Think of those like Father Maximilian Kolbe – starving in a bunker in Auschwitz, offering his life for a stranger. And think of those like the fictional Father Rodrigues in Silence – stepping on the holy image to save his followers.

One was considered a hero; one a “failure.” Yet both were lights.

Both chose love over the system. Both took the leap.

So, to my fellow seekers, doubters, and “bad” believers: Do not be afraid of your questions. Do not be afraid of the silence.

The opposite of faith is not doubt. The opposite of faith is CERTAINTY.

Take the leap. The bridge is there.

Love never fails. But where there are prophecies, they will cease; where there are tongues, they will be stilled; where there is knowledge, it will pass away. For we know in part and we prophesy in part, but when completeness comes, what is in part disappears. When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put the ways of childhood behind me. For now we see only a reflection as in a mirror; then we shall see face to face. Now I know in part; then I shall know fully, even as I am fully known.

1 Corinthians 13:8-12

Other resources you might be interested in:

- Nihilism vs Existentialism vs Absurdism: A Journey Into the Abyss

- How to Deal with Existential Dread: A Seeker’s Guide to Finding Light

- The World is Not Black and White: Finding Grace in the Grey

- Hiroshima Rages, Nagasaki Prays: A Personal Reflection on Peace & Meaning

- 40 Spiritual Lessons: Wisdom for Life’s Journey

Let’s Tread the Path Together, Shall We?