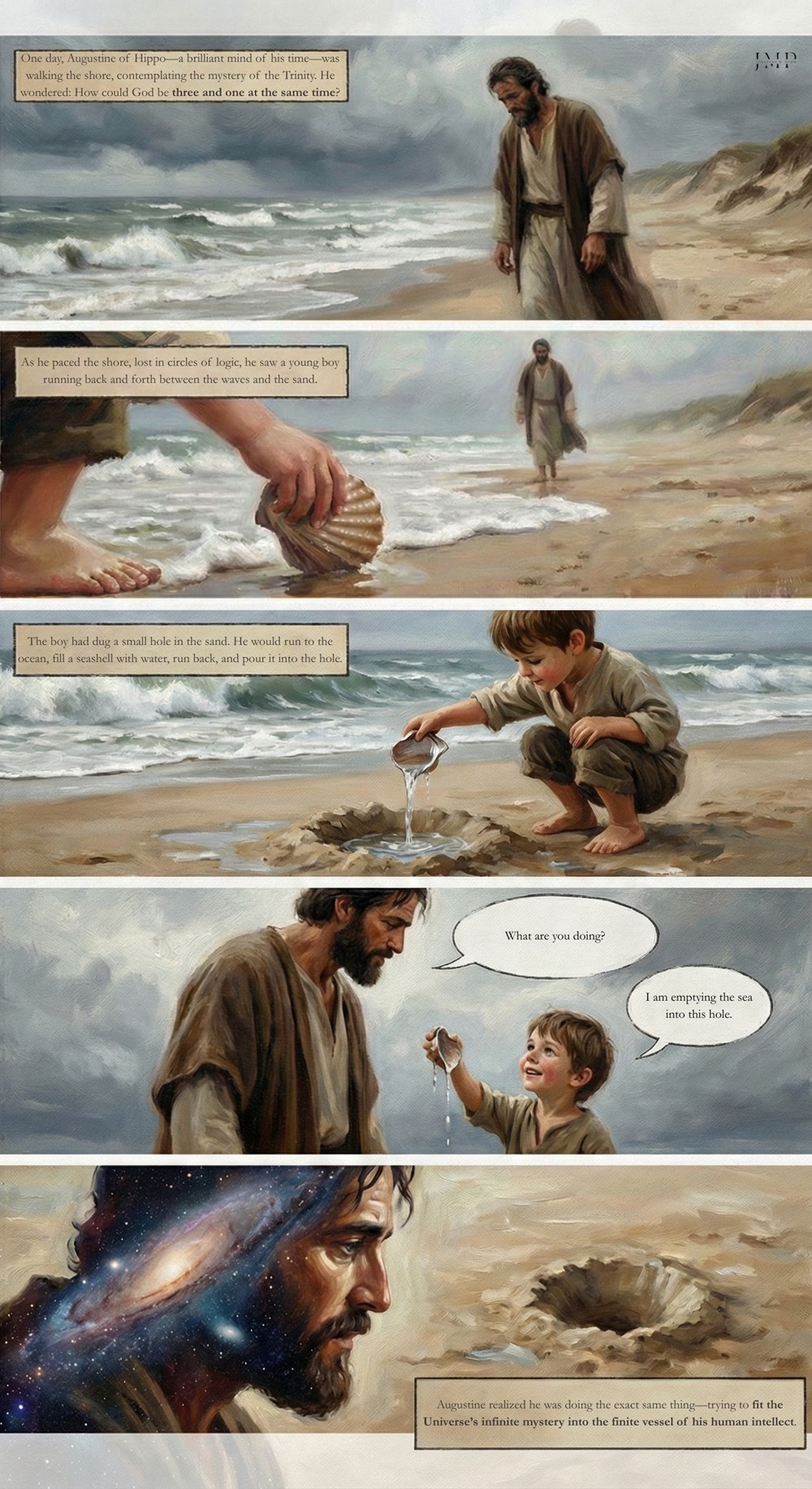

There is an old story, often attributed to St. Augustine, that perfectly captures the feeling of wrestling with a mystery too big for the human mind.

The story goes that Augustine, one of the greatest intellects of his time, was walking along the beach, exhausted. He was trying to wrap his head around the mystery of the Trinity—how God could be three and one at the same time. As he paced the shore, lost in circles of logic, he saw a young boy running back and forth between the waves and the sand.

The boy had dug a small hole in the sand. He would run to the ocean, fill a seashell with water, run back, and pour it into the hole.

“What are you doing?” Augustine asked.

The boy looked up, smiling. “I am emptying the sea into this hole.”

Augustine realized then that he was doing the exact same thing. He was trying to fit the infinite mystery of the Universe into the finite vessel of his human intellect.

I share this because, for the past few weeks, researching the topic of Free Will has made me feel exactly like that boy on the beach.

It is one of the oldest and most frustrating debates in human history. Trying to understand if we truly have agency—if we are the authors of our own lives—often feels like trying to pour the whole ocean of universal causality into the tiny seashell of our daily understanding.

If you have ever lain awake at night wondering if you are truly in control, or if reading about this topic makes you feel like your brain is about to explode, please know: you are not alone.

In fact, that confusion is where the journey begins.

Highlights

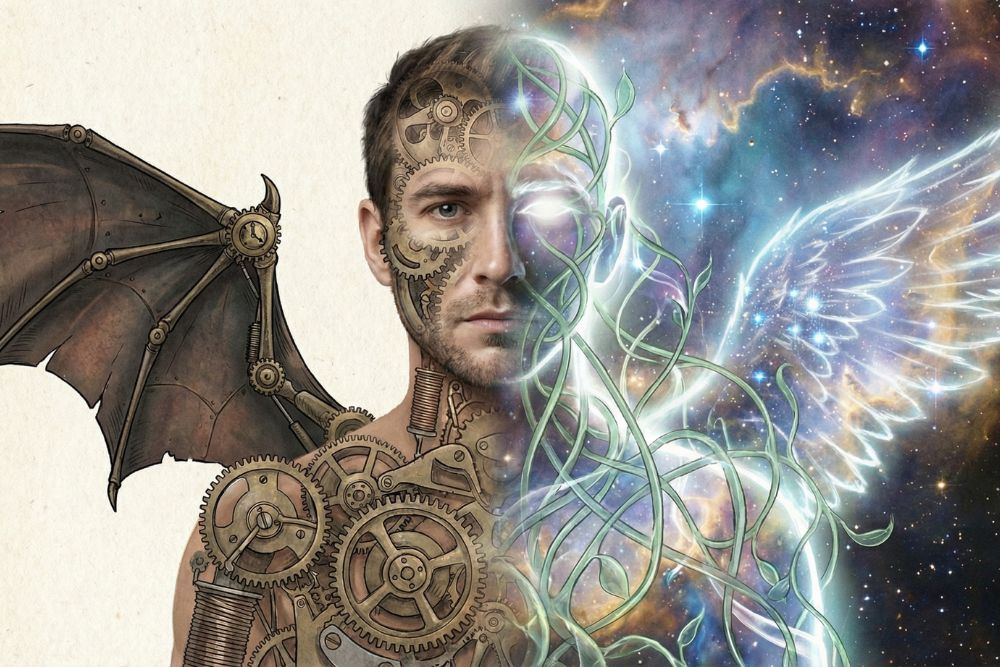

- A profound tension exists between the daily subjective sense of agency and scientific arguments from physics, neuroscience, and biology, which propose that humans are biological machines shaped by forces beyond their control.

- The view of “Total Freedom” gives rise to anxiety, as observed by existential philosophers, while the opposing view of “Total Determinism” runs the risk of moral apathy and a loss of human dignity.

- From the perspective of Compatibilism and Eastern philosophy, free will can be reframed not as the ability to control the universe, but to “play the hand” one is dealt with grace and “effortless action” (Wu Wei).

- Cultivating the “Space” between stimulus and response through mindfulness enables individuals to break deterministic scripts and act with the courage of authenticity.

- To embrace agency, one can adopt an “asymmetrical” approach to living—i.e. holding oneself responsible while treating others with empathy and embracing all life has to give with faith and action.

What is Free Will?

Free Will is traditionally defined as the capacity of agents to choose between different possible courses of action unimpeded.

In the context of self-discovery, it represents the tension between two opposing forces:

- Determinism: The scientific view that our actions are shaped by biology, physics, and past events (the “Machine”).

- Agency: The subjective feeling that we are the authors of our own lives (the “Captain”).

Below, we will explore how we can reconcile these views to find a practical “Middle Way” and live with purpose.

The Paradox of Free Will

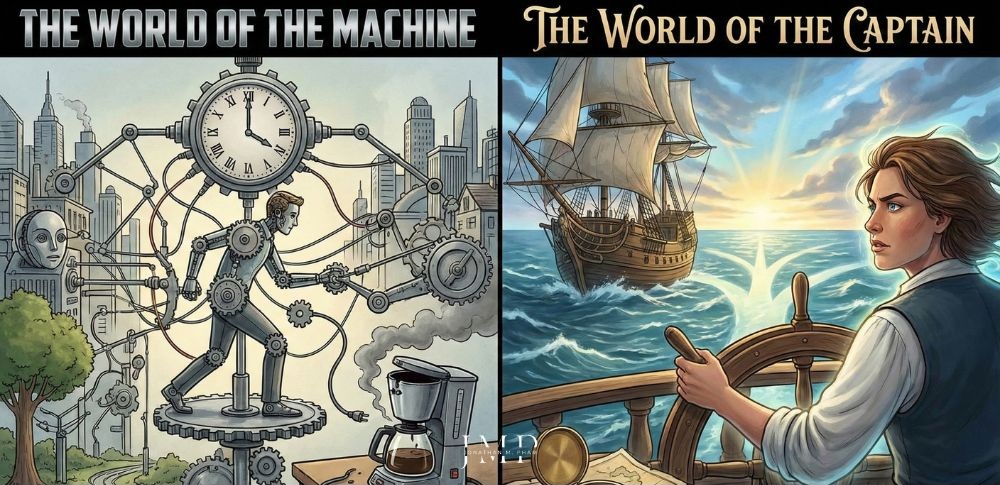

We live our lives in two completely different worlds. In fact, most of us toggle between them a dozen times before breakfast without even noticing.

- World #1: The world of the Machine

Imagine your coffee machine breaks tomorrow morning. You press the button, and nothing happens.

Do you get angry at the machine? Do you accuse it of being “lazy” or “immoral”?

Of course not. You assume there is a cause. A fuse blew. A wire came loose.

You accept that the machine is part of a “clockwork” universe governed by physics. If you fix the cause, you fix the result.

- World #2: The world of the Captain

Ten minutes later, you sit down to work, but instead, you scroll through social media for an hour. Or perhaps you snap at your partner because you are stressed.

Suddenly, the logic changes. You don’t look for a “loose wire” in your brain. You feel guilt. You blame yourself. You feel an intuitive sense that you could have done otherwise.

Nobody is exempt from this tension. We view the entire universe—from the stars to our toasters—as a chain of cause and effect. But when it comes to us, we feel like the “Captain of the Ship,” steering our vessel freely through the waves.

In other words, humanity lives in the intersection of physics and poetry.

Do We Have Free Will?

So, which view is true?

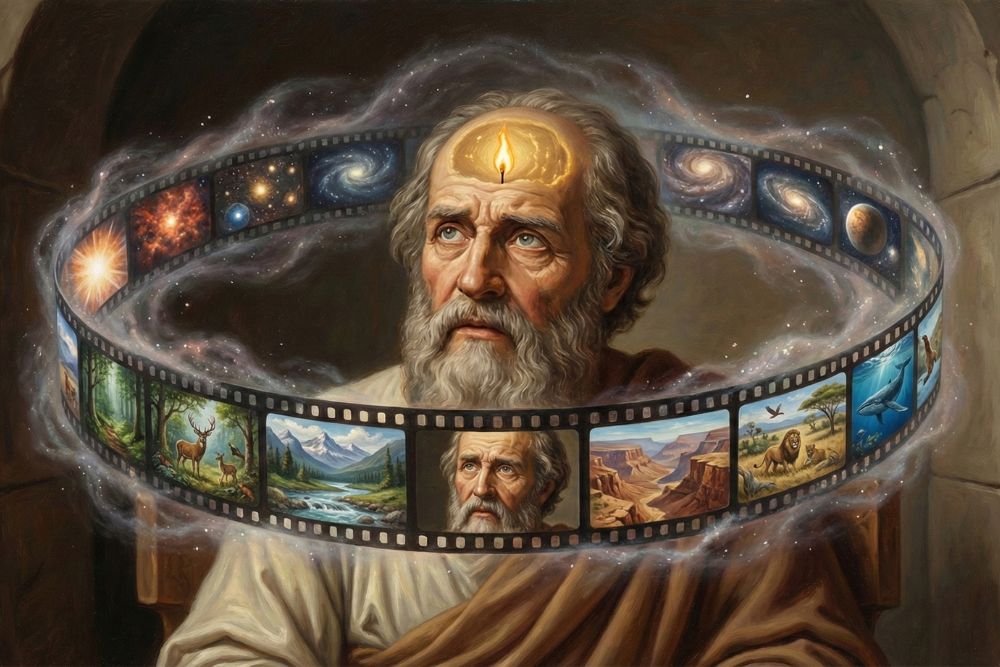

Is the “You” currently reading this article truly the ultimate originator of your thoughts? Or are you just a passenger—a conscious observer watching a movie that was filmed and edited at the moment of the Big Bang?

This isn’t just a logic puzzle for philosophy professors in ivory towers. The answer to this existential question dictates everything about how we live.

It shapes how we judge criminals (are they evil, or just broken?).

It shapes how we forgive our parents (did they choose to hurt us, or were they acting out their own trauma?).

And above all, it shapes how we view our own achievements and failures.

Free will question: Do we have free will, or is everything predetermined?

The good news is: We are NOT here to solve the debate.

Brilliant minds, from the ancient Stoics to modern neuroscientists, have deadlocked on the argument for centuries. We are not trying to solve the math of the universe here.

Instead, our goal is to find a pragmatic way to live.

If we lean too far into “Total Control,” we become arrogant judges of others and anxious wrecks about ourselves.

On the other hand, if we lean too far into “No Free Will,” we risk becoming apathetic passengers, drifting through life like leaves in the wind.

For my part, I believe there is a “Middle Way”. A way that allows us to look at the science without losing our souls. To accept the hand of cards we were dealt, while still playing it with courage.

It’s a view that allows us to get back to life—connecting with loved ones, doing work, and existing not as robots, but as the “salt and light” of the world.

But first… let us look at why the scientists think we might be robots after all.

Scientific Perspectives: Arguments Against Free Will

For centuries, we humans believed we were the kings of our own castles. We sat at the center of existence, believing the sun revolved around us—and that we were the undisputed masters of our own minds.

But slowly, science has surrounded the castle, taking away our territory piece by piece.

First, astronomy proved we weren’t the center of the universe. Then, biology concluded we were evolved animals, not divine statues. And now, neuroscience and physics are knocking on the door of the last room we have left: our own minds.

They come bearing a difficult message: The “feeling” of freedom you have might just be a trick of the light.

The physics argument: The unbroken chain

Free will is an illusion. Our wills are simply not of our own making.

Sam Harris

The first battering ram against free will comes from simple physics. It is the idea of the “Clockwork Universe,” often personified by a concept called Laplace’s Demon.

Imagine a giant pool table. If you hit the cue ball (the “break shot”), the balls scatter. If you knew the exact position of every ball, the friction of the table, and the force of the hit, you could—using the laws of physics—predict exactly where every ball would end up. They have no choice. They are just obeying the laws of motion.

Now, let us apply that to the universe.

The Big Bang was the ultimate “break shot.” It sent matter hurling through space. Over 13.8 billion years, that matter formed stars, planets, and eventually, you.

Since your brain is made of atoms, and atoms obey the laws of physics, every electrical impulse in your head right now is arguably just the result of a chain of collisions that started at the beginning of time.

From this view, you didn’t “choose” to read this sentence. The laws of physics determined you would read it billions of years ago. You are just watching the dominoes fall.

What is free will in physics

Some of you might be shouting at the screen right now: “But what about Quantum Mechanics? Isn’t the universe random?“

It is true that modern physics has moved past the rigid ‘Clockwork Universe’ of Newton. We now know that at the subatomic level, things are probabilistic, not certain.

But be careful not to mistake randomness for freedom. If your choices are merely the result of random quantum fluctuations, you are still, technically, NOT in control—you are just a dice roll rather than a domino. The problem of agency remains.

The biological argument: The “Ovarian Lottery”

This is that human freedom, which all boast that they possess, and which consists solely in the fact, that men are conscious of their own desire, but are ignorant of the causes whereby that desire has been determined.

Baruch Spinoza

“Okay,” you might say. “But I’m not a billiard ball. I’m a complex human being with a personality.”

This brings us to the second challenge: Biology.

We tend to think our personality is “Us”—something we crafted. But thinkers like Stanford neurobiologist Robert Sapolsky argue that biology and environment eliminate the room for a “ghost in the machine”.

Think about Warren Buffett’s theory of the “Ovarian Lottery.” You did not choose your parents. You did not choose your genes. You did not choose whether you were born in a war zone or a suburb. You didn’t choose the trauma you suffered at age five, or the nutrition you received at age ten.

Yet, these are the exact things that built your brain.

If your “choices” today are based on your personality, and your personality was decided by genes and environments you didn’t choose, can you really claim credit for the result?

It’s like being dealt a hand of cards. You are holding the cards, yes. But the deck was shuffled and dealt long before you sat at the table.

Free will is not real

The neuroscience argument: The delayed broadcast

If physics and biology aren’t enough to shake you, neuroscience may be the one to deliver the most personal blow.

In the 1980s, a researcher named Benjamin Libet conducted a set of experiments. He asked participants to move their fingers whenever they felt like it, while he monitored their brain activity.

The results were unsettling. The brain scans showed that the brain prepared to move the finger before the participants were consciously aware of their decision to move it. The “readiness potential” fired milliseconds before the “I decided” thought appeared.

In other words, our conscious mind—the voice in your head saying “I decided to do this”—might just be a narrator telling a story after the fact.

We like to think we are the King ruling the country. But it seems we might actually be a King who is asleep, while the Generals (our subconscious biology) send the troops to war.

The King wakes up later, sees the troops moving, and says, “Yes, I ordered that.”

The logical deconstruction: The “Tiny Man” fallacy

You are not controlling the storm, and you are not lost in it. You are the storm.

Sam Harris

Now, we arrive at the logical problem. When we say “I have free will,” who is the “I”?

We intuitively feel like there is a “Controller” or an “Owner of the Will” sitting somewhere behind our eyes, pulling the levers. But let’s look for him.

If you lose an arm, you are still “You.” If you lose a leg, you are still “You”. But where does the “You” live?

If we keep removing parts, we eventually get to the brain. But the brain is just tissue, neurons, and chemistry. There is no “Tiny Man” (Homunculus) sitting inside the brain piloting the ship.

There is no “Owner.” There is only the ship (the biological organism) reacting to the ocean (the environment).

The “You” that feels in control is, perhaps, just a belief—a necessary fantasy the brain creates to make sense of its actions.

Illusion of free will

Why Free Will Terrifies Us

If physics determines the atoms, biology determines the temperament, and the brain decides before we know it… what is left?

This line of thinking leads us to the “Abyss”—the feeling that we might just be biological robots suffering from a delusion of grandeur. It feels like a loss of humanity.

It’s a thought that can easily drive one to despair, I know. Some, I suppose, may just outright reject it and say: “No, we DO have the freedom to choose! I am the master of my fate!”

That seems fair enough. But what if we just pause for a moment to reflect on this question?

“If we did have total freedom… would we actually WANT it?”

The burden of no excuses

Now, let us assume the scientists are wrong and we are truly free. In that case, we face a problem that is arguably even scarier than being a robot: Total Responsibility.

The French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre once commented as follows:

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does.“

Notice the word “condemned”. Sartre didn’t say we are “blessed” to be free. He argued that because we did not create ourselves, yet we are thrown into a world where we are responsible for everything we do, freedom is a heavy burden.

If you are free, you have no excuses. You cannot say, “My nature made me do it,” or “My passion overcame me”.

As Sartre argued, every time you act, you are choosing your own nature. If you are angry, it is because you chose to be angry rather than to restrain yourself.

If you fail, there is no “System” to blame. The failure is YOURS alone.

And with responsibility comes this feeling which existential philosophers called Angst.

The anxiety of infinite choice

Anxiety is the dizziness of freedom.

Søren Kierkegaard

Let’s say you are standing on the edge of a high cliff. You feel anxiety not just because you might accidentally fall (which is a deterministic fear, like gravity). Rather, it’s because you realize that you are free to jump.

The only thing stopping you is… you.

That vertigo—that realization of infinite possibility—is dizzying. In fact, it is so uncomfortable that many of us subconsciously try to escape it.

Free will philosophy

I happen to know someone personally who operates this way. Whenever a conflict arises in the family, instead of reasoning fairly or owning their part in the mess, they would retreat immediately into the role of the “oppressed”. They would bring up past traumas that have nothing to do with the current argument, or they say things like, “I don’t know, maybe I’m just stupid…” .

Why do they do this?

Because playing the victim is safe. It absolves them of the need to solve the problem or change their behavior.

Sartre called this “Bad Faith” (mauvaise foi). It is the lie we tell ourselves that we have no choice. We say things like,

- “I know this isn’t the best way to do it, but my boss told me to do so,” or

- “I had to stay at this job for the stability”.

By pretending to be an object—a cog in the machine—we escape the dizziness of being a subject.

Read more: Living in the Past – The Problem of Dwelling on What Was

The collapse of the “Old Laws”

This anxiety is sharper today than ever before. For most of history, humans didn’t have to “create” their own meaning. The “Old Laws” did it for them. Religion told you what was good; tradition told you who to marry; the social structure told you your place.

But in the modern era, those fragile “laws” have been shattered.

The Enlightenment and scientific progress invalidated many institutional theories humanity once assumed were absolute.

Today, technological advances are reshaping everything, deleting jobs once considered prestigious—while creating new ones that didn’t exist a decade ago.

The script is gone. We are improvising. And when we look into the void of meaning and ask, “What should I do?”, the universe remains silent.

Three responses to the “Abyss”

So, how do we live when the script is lost?

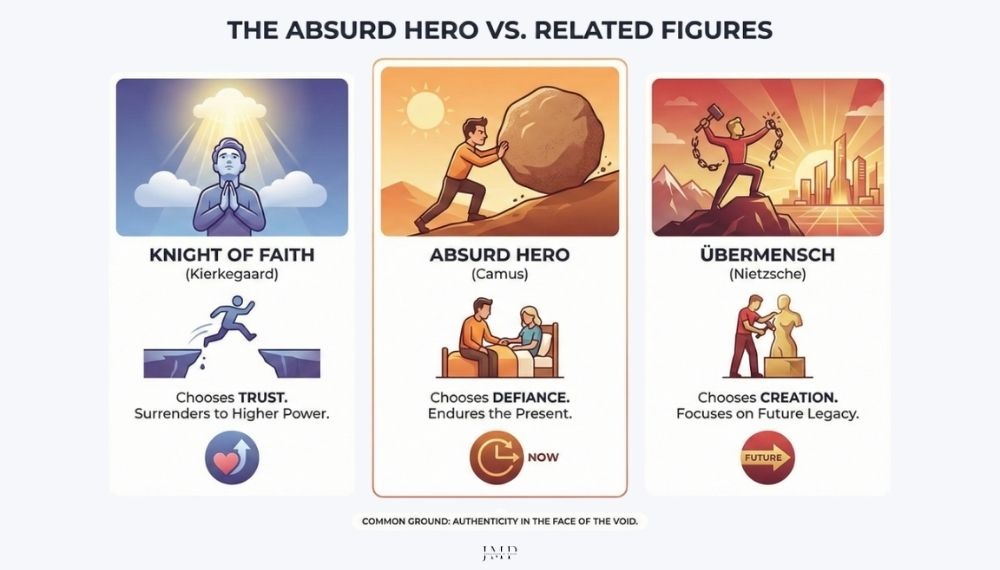

Existential philosophers proposed that we could look up to three “Heroes” to show us the way.

- The Knight of Faith (Kierkegaard)

In the 19th century, the philosopher Hegel concluded that logic and history formed a perfect “System” that could explain everything. This view—though widely hailed at the time—was rejected by Søren Kierkegaard, who is considered the “father of existentialism”.

Kierkegaard argued that for the things that actually matter—love, meaning, God—proof is useless. When it comes to such things, one must act like a “Knight of Faith”. They must take a “leap of faith“—not because they have scientific proof or logical certainty, but because they have passion.

In other words, they risk everything on a commitment without a guarantee.

- The Übermensch (Nietzsche)

Friedrich Nietzsche, another existential philosopher, looked at the collapse of religious structure at his time and declared, “God is dead“. Rather than a celebration, his statement was a warning that the external rulebook was gone.

His hero, the Übermensch (Overman), doesn’t look for a new “System” to tell him what is good. He has the courage to “dance on the edge of the abyss”.

He realizes he is the author of his own life—that he creates his own values, and that he is capable of transforming the chaos of existence into something beautiful.

- The Absurd Hero (Camus)

Years later, Albert Camus took it a step further. He believed that the universe is silent and indifferent, and looking for meaning in it is “Absurd”. According to him, we should look up to the model of Sisyphus—the mythical king condemned by the Greek gods to push a boulder up a hill, only to watch it roll back down, forever.

Sisyphus knows his task is futile (the rock will always roll down), but he pushes it anyway. His freedom—and his victory—lies in his refusal to surrender to the silence.

The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.

Albert Camus

Nihilism or opportunity?

There is a real danger we should be aware of here. If we realize the “System” isn’t watching, we risk falling into Nihilism (“If nothing matters, why bother?“) or destructive hedonism (“If God did not exist, everything would be permitted” – to quote Dostoevsky).

But this “Terror of Freedom” is also our greatest opportunity.

If you are forced to be good—like the protagonist in A Clockwork Orange who is conditioned to be unable to choose violence—you aren’t actually “good”. You are just a broken machine.

Authenticity is the flip side of free will. It allows us to tear off the “social masks” and be real.

As the author C.S. Lewis noted,

“Free will though it makes evil possible, is also the only thing that makes possible any love or goodness or joy worth having.“

We have to choose: Do we want the safety of the robot, or the risk of the lover?

Arguments for Free Will: The Trap of Total Determinism

I suppose that contemplating the “Abyss of Freedom” may have given you a panic attack. That some of you might be thinking:

“You know what? Maybe the scientists were right. Maybe I am just a biological robot. Maybe none of this is my fault.”

There is, indeed, a feeling of comfort in thinking that way. It is tempting to believe we are just products of our environment—because it absolves us of guilt.

But before you sign up for that worldview, you need to see the fine print. While the cage of determinism is comfortable, it is STILL a cage.

“It’s not my fault”

Fear is the path to the dark side.

Yoda, ‘Star Wars’

The immediate appeal of Hard Determinism is that it erases shame. If you fail, it was because of your genetics. If you lash out, it was because of your trauma.

But there is a high price for it: Apathy.

If you accept that you have no real control, you surrender your agency.

If you believe you are helpless—that you are just a result of inputs and outputs—it becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. You stop trying to improve your life, because you feel the outcome is already fixed.

By refusing to take the blame, you also inadvertently refuse the power to change.

We do not suffer from the shock of our experiences—the so-called trauma—but instead we make out of them whatever suits our purposes. We are not determined by our experiences, but the meaning we give them is self-determining.

Ichiro Kishimi, ‘The Courage to be Disliked’

The ethical dead end

What is the point of so many admonitions, so many precepts, so many threats, so many exhortations, so many expostulations, if of ourselves we do nothing?

Erasmus

The problem gets even darker when we look at how we treat others.

Let us pause for a moment to reflect on the difficult reality of the criminal justice system. Research on death row inmates has revealed that a high proportion of these individuals had issues with their prefrontal cortexes—the part of the brain responsible for emotional control and resisting urges.

From a strict Determinist view, we may look at these men and say: “It’s NOT their fault. Their brain is broken. They are like a car with cut brakes.”

There is, indeed, a deep compassion in this view, and it drives important discussions about rehabilitation over punishment. However, if we take it to the extreme, we run into a “Broken Machine” problem.

If we treat everyone merely as broken machines, we lose the concept of Justice. There’s the risk of justifying heinous acts because “the universe made me do it”.

Worse, we strip humans of their dignity. To treat a person only as a set of biological causes is to treat them as an object, not a subject.

We might save them from blame, but we also rob them of their humanity.

The pragmatic reality check

So, it seems that we are trapped, right? We can’t scientifically prove we have free will, and yet we can’t ethically live without it either.

This brings us to what Christian List, a Professor of Philosophy at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (LMU), refers to as the “Category Mistake.”

In a thoughtful analysis of the topic of free will, List compared explaining human choices via physics to trying to analyze the stock market by looking at the electrons in a computer screen.

Technically, the stock market is just electrons moving around. But if you try to explain a market crash using particle physics, you will fail. Because you are looking at the wrong “level of description”.

To understand the market, you need concepts like “value,” “fear,” and “trade.”

The same applies to us. You CANNOT explain human life using only atoms.

Just try a real world test. The next time you forget your spouse’s birthday, try telling them, “Honey, it wasn’t me. The Big Bang set off a chain of events 13.8 billion years ago that necessitated this moment. I had no choice.”

See how that goes over.

The truth is, agency is indispensable. We need concepts like consent, contracts, apologies, and promises to make society function.

Even if physics says we are robots, we must live as agents.

Is free will real or an illusion? TED Talk by Prof. Christian List

Transition to a “Middle Way”

So here we are, stuck between a rock and a hard place.

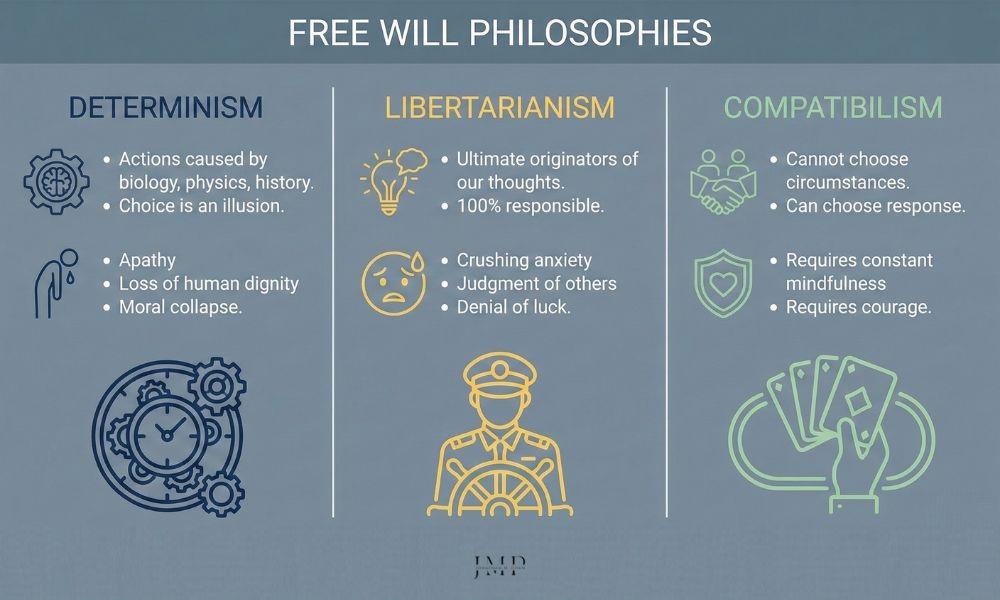

Path A (Total Freedom) leads to crushing anxiety and the arrogance of the Judge. Path B (Total Determinism) leads to apathy and the moral collapse of the Broken Machine.

Is there a third option?

Is it possible to accept the “hand we were dealt” (Determinism) while still taking full responsibility for “playing the cards” (Free Will)?

I believe there is. In fact, it is an idea found in both Western Compatibilism and Eastern philosophy—a way of finding freedom not from our constraints, but WITHIN them.

(Note: For those who are not familiar with it, Compatibilism is the philosophical view that free will and determinism are not mutually exclusive—they can both be true.)

Fate vs free will: There is a middle way

Reframing the Debate: Relative Free Will

I donʼt know if we each have a destiny, or if weʼre all just floating around accidental-like on a breeze, but I, I think maybe itʼs both. Maybe both is happening at the same time.

Forrest Gump (1994)

If you are feeling exhausted by the tug-of-war between “I am a Robot” and “I am a God,” I have a suggestion: just put down the rope.

Much of our frustration with the topic of free will comes from the fact that we are chasing a fantasy.

We want Absolute Free Will. We want to be the “Ultimate Originator”—a being who can act completely independent of biology, history, or physics.

But that kind of freedom is a ghost. It doesn’t exist.

Instead, I would like to offer you a different kind of freedom. A freedom that is smaller, perhaps, but infinitely more real. Let’s call it Relative Free Will.

Think of it this way: “Freedom” isn’t the ability to flap your arms and fly to the moon. That would be breaking the laws of physics.

Rather, it is the ability to walk wherever you want WITHIN the laws of gravity.

Most of our discussions shouldn’t be about whether we can break the laws of the universe, but about how we navigate the space we are actually given—our “Relative Free Will” within our circumstances.

No matter how much you want to be Y, you cannot be reborn as him. You are not Y. It’s okay for you to be you. However, I am not saying it’s fine to be ‘just as you are’. If you are unable to really feel happy, then it’s clear that things aren’t right just as they are. You’ve got to put one foot in front of the other, and not stop.

To quote Adler again: ‘The important thing is not what one is born with, but what use one makes of that equipment.’ You want to be Y or someone else because you are utterly focused on what you were born with. Instead, you’ve got to focus on what you can make of your equipment.

Ichiro Kishimi, ‘The Courage to be Disliked’

The Poker game example

To make the idea concrete, let us look at life through the lens of a card game. This is the core of the Compatibilist view—the idea that determinism and free will can sit at the same table.

Free will examples

- The Deal is Determinism

You did not choose your hand. You didn’t pick your parents, your genetic predisposition to anxiety, the century you were born in, or the trauma you suffered as a child.

That part of your life is “determined.” It is the “System” dealing you cards based on physics, biology, and history.

- The Play is Free Will

But here’s the crucial part: You have total freedom in how you play that hand. You can fold, bluff, or go all in. The cards are fixed, but the strategy is yours.

Freedom doesn’t mean “doing anything you want.” It means having the power to choose your attitude and next action within the boundaries of your current situation.

In this sense, your free will acts as the “Input Device” for the universe. Your past created your present, but your current choice creates your future reality.

| Perspective | Core Belief | Metaphor | The Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Determinism (Arguments Against Free Will) | Actions are caused by biology, physics, and history. Choice is an illusion. | The “Machine” or “Clockwork Universe” | Apathy, loss of human dignity, moral collapse. |

| Libertarianism (Arguments For Free Will) | We are the ultimate originators of our thoughts. We are 100% responsible. | The “Captain of the Ship” | Crushing anxiety, judgment of others, denial of luck. |

| Compatibilism (The “Middle Way”) | We cannot choose our circumstances, but we can choose our response. | The “Poker Game” (Hand vs. Strategy) | Requires constant mindfulness and courage. |

Determinism vs Libertarianism vs Compatibilism

Read more: Finding Meaning in Suffering – How to Turn Wounds Into Wisdom

Controlling the “Internal”

Man can DO what he wills, but he cannot WILL what he wills.

Arthur Schopenhauer

It sounds like a riddle, right? However, if you look at it closely enough, you should see that Schopenhauer’s observation is actually a practical guide.

It means you can choose to eat a sandwich (action), but you cannot choose whether or not you are hungry (desire).

Your desires are thrust upon you by biology. Your freedom lies in whether you act on them.

This is the heart of philosophies like Stoicism.

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus taught people to practice the “Dichotomy of Control.” According to him, we need to draw a hard line between what is up to us (our opinions, pursuits, desires, aversions) and what is not (our body, property, reputation).

One great example for this came from the story of Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist who survived the terror of the Holocaust. In the concentration camp, he observed that the Nazis could take away one’s identity, family, and physical freedom. However, they could not take away “the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way”.

Even in a setting of total physical determinism, Frankl—along with many inmates—was still able to find a space for agency.

In the concentration camps, for example, in this living laboratory and on this testing ground, we watched and witnessed some of our comrades behave like swine while others behaved like saints. Man has both potentialities within himself; which one is actualized depends on decisions but not on conditions.

Viktor Frankl, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’

The necessity of constraints

You must, therefore you can. A free will and a will subject to moral laws are one and the same thing.

Immanuel Kant

Many of us assume that limitations are the enemy of freedom. However, the truth is, without boundaries, the idea of freedom becomes amorphous and meaningless.

Imagine if you could do anything. Imagine a world with no gravity, no history, no consequences, and no biological drives. Your choices would be weightless. They would be random.

True freedom isn’t the absence of limitations. It is the ability to navigate and make choices within a given framework.

It is the creativity of the poet working within the strict rules of a sonnet, or the jazz musician improvising within a chord progression. The constraint is what makes the art beautiful.

Realizing this is only the first step, though. To be truly free requires a great deal of “inner workings” to break through one’s internal horizons.

If we accept the hand of cards we were dealt, how do we play it with grace? How do we stop fighting the “Dealer” (the Universe) and start playing the game?

The “Right View” of Free Will

If the discussion so far feels heavy to you, there is a reason.

Western philosophy, for all its brilliance, tends to feel like a weightlifting competition.

The Western Existentialist is like a sculptor trying to hammer meaning out of a hard, indifferent rock.

The Stoic, on the other hand, is like a soldier standing guard at his post.

Both assume that life is a battle between a separate “Little Man” (the Ego) and a giant, chaotic Universe.

But what if the “Little Man” doesn’t exist?

What if the wave stopped trying to separate itself from the ocean?

If Western thought asks, “How do I force my will on the world?“, Eastern thought asks a much different question:

“Who is the ‘I’ that is willing?“

The Ego problem

A flower, like everything else, is made entirely of non-flower elements. The whole cosmos has come together in order to help the flower manifest herself. The flower is full of everything except one thing: a separate self, a separate identity.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Remember the “Tiny Man” fallacy we discussed earlier? We intuitively feel there is an “Owner of the Will” inside our heads.

But as we discovered, if you peel back the layers of biology, you don’t find a pilot; you just find the ship.

Buddhism takes this realization and turns it into a path to freedom—which is reflected through concepts like Anattā (No-Self) and Pratītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination).

The logic is simple: You are NOT a static noun; you are a verb.

You are a process made entirely of “non-you” elements—your parents’ genes, the food you ate (which came from the earth), the culture you learned language from, and the sun that warms the planet.

If you remove all these “non-you” elements, there is no “you” left.

The idea may sound scary, but if you really think about it, it actually brings about a massive relief.

If there is no separate “Controller,” there is no one to blame and no one to defend. The crushing anxiety of “Am I good enough?” or “Did I make the right choice?” dissolves into the reality of connection.

You realize that you are not an isolated entity fighting the universe; you are the universe expressing itself as a human being.

Read more: The Excessive Need to Be Me – When the Ego Takes Over

The “Swamp” of Being

Speaking of this tension between the Western desire to conquer and the Eastern reality of “being”, I cannot help but recall a haunting scene from Martin Scorsese’s masterpiece Silence (which was adapted based on Shusaku Endo’s novel) – when the apostate priest Ferreira tells the protagonist, Father Rodrigues, of an ancient proverb:

“Mountains and rivers can be moved, but man’s nature cannot.”

On the surface, it sounds like a cynical excuse for his betrayal. (i.e. renouncing the Christian faith) But deeper down, Ferreira is arguing against the Western myth of the “Plastic Soul”—the idea that we can be whoever we want, regardless of our context. He describes Japan (and by extension, the human condition) as a “mudswamp.” One can plant a seed of an idea or faith in it, but the swamp doesn’t change; it eventually transforms the seed.

In other words, we do not float above the world as disembodied spirits; we are “thrown” into a specific time, body, and culture. We are the swamp.

Our core—our fears, survival instincts, cultural roots—is a bedrock that no amount of logic or inspiration can truly shift.

To believe we can simply “will” ourselves out of our nature is not freedom at all—it is simply a delusion.

True freedom, therefore, starts not by fighting the swamp, but by acknowledging we are made of it.

As thrown, Dasein has indeed been delivered over to itself and to its potentiality-for-Being, but as Being-in-the-world. As thrown, it has been submitted to a ‘world’, and exists factically with Others.

Martin Heidegger

The art of effortless action

So, if we aren’t separate, how do we make choices? Do we just give up?

No. We learn to swim.

In Taoism, this principle is called Wu Wei (無為), often translated as “Non-doing” or “Effortless Action”. However, don’t mistake it for laziness.

- The Existentialist tries to swim upstream, fighting the current with sheer willpower.

- The Determinist floats like a dead log, letting the current take them into the rocks.

- The Taoist swims with the current, using the water’s own power to navigate.

Let us think of a tree. A tree does not have an existential crisis about whether to grow. It doesn’t look at the other trees and ask, “Am I growing correctly?”

It simply follows its Te (徳, inner nature) without resistance. It acts with perfect purpose, yet it never “struggles.”

This is the core of Eastern agency. You don’t force things to happen; you align yourself with the flow of reality so that right action happens through you.

Man is not the lord of beings. Man is the shepherd of Being. Man loses nothing in this “less”; rather, he gains in that he attains the truth of Being. He gains the essential poverty of the shepherd, whose dignity consists in being called by Being itself into the preservation of Being’s truth.

Martin Heidegger

My freedom is tied to yours

Ubuntu: “I am because you are”.

African Philosophy

If we are able to adopt such a shift in perspective, there will be a radical change in how we view our responsibility to others. Specifically, we realize that nobody exists in a vacuum. (no man is an island)

To quote the Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh, “to be is to inter-be“.

When we understand this, the concept of “Free Will” stops being a selfish obsession.

Why? Because our actions ripple outwards, creating consequences that impact the entire web of life.

If I choose to scream in traffic, I am not just venting “my” anger; I am putting anger into the system, which travels to the other driver, then to their family, and so on.

If I choose compassion, I am healing a part of the whole.

The “Void” or “Emptiness” spoken of by mystics—East and West alike—isn’t a nihilistic black hole where nothing matters. It is a fullness.

It is the realization that because we are empty of a separate self, we are full of the universe.

When we stand before the mountain or flower and visualize just before we touch the earth the second time, we see that we are not only bodhisattvas but we are also the victims of oppression, discrimination and injustice. With the energy of the bodhisattvas we embrace victims everywhere. We are the pirate about to rape the young girl and we are the young girl who is about to be raped. Because we have no separate selves, we are all interconnected and we are with all of them.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Free will is a “pathless land”

Truth is a pathless land.

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Here is where East meets West. From the West, we take the responsibility of Karma—the undeniable fact that our actions DO have consequences.

From the East, we take the wisdom of dropping the rigid Ego—the attachment to being “right” or “in control.”

The result is a new way of living. Instead of “daring to be wrong” just to prove we exist, we now act with what the Taoists call Ziran (自然, meaning “spontaneity”).

We do the right thing not because a commandment told us to—nor because we are afraid of the abyss—but because it is the most natural thing to do in that moment.

We stop trying to be the “Captain” of the ocean, and start learning to be a skilled surfer.

The call comes as the throw from which the thrownness of Da-sein derives. In his essential unfolding within the history of Being, man is the being whose Being as ek-sistence consists in his dwelling in the nearness of Being. Man is the neighbor of Being.

Martin Heidegger

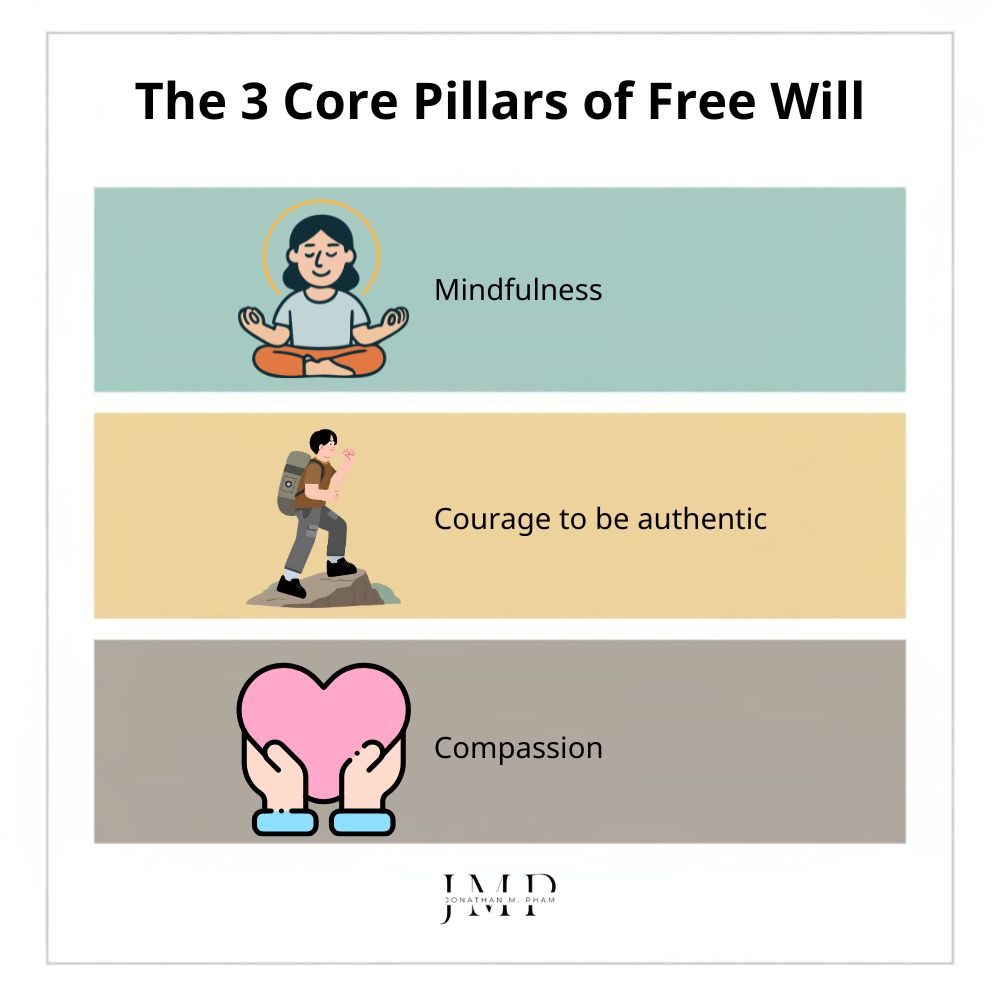

The 3 Core Pillars of Free Will

By now, we have accepted that we are not gods who can control the universe. That we are part of a vast, interconnected web of biology and history. That we need to stop fighting the ocean and start “surfing” instead.

But how do you actually “surf”?

When your boss screams at you, or your spouse makes that sarcastic comment that hits your exact insecurity, philosophy goes out the window. Your heart races, your stomach tightens, and before you know it, you have snapped back. The “robot” has taken over.

How do we interrupt that program then?

Mindfulness

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

Viktor Frankl

I believe this is one of the most practical definitions of free will you will ever find. It’s not about controlling the stimulus—you cannot stop the boss from yelling or the traffic from jamming.

Free will is entirely about widening the “space” before you react.

What is free will in psychology

How? The answer lies in practicing mindfulness.

Free will is only possible when we are mindful. Otherwise, we are driven by sense desires and impulses—which effectively operate as biological machines.

It is only when we are mindful that we can choose to assent to an impulse or dissent from it.

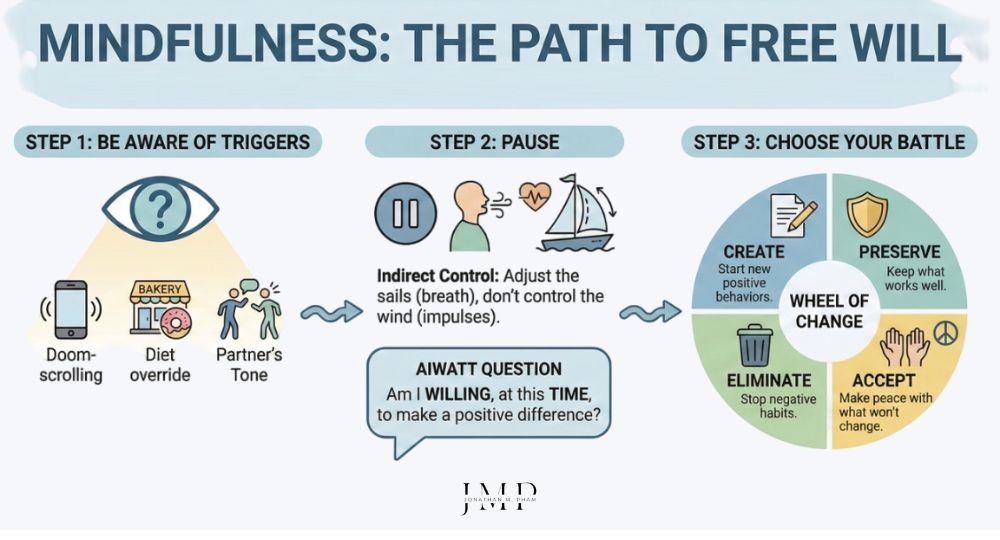

Here is a three-step guide to “hacking” your own programming.

Step 1: Be aware of the triggers

First, we have to admit a humbling truth: We are “superior planners” but “inferior doers”.

We plan to be patient and kind when we are sitting calmly on the sofa. Yet most of us fail to execute that plan when we are tired, hungry, or stressed.

Why? Because, as pointed out by executive coach Marshall Goldsmith in his book Triggers, our environment acts as a “triggering mechanism” that constantly reshapes us.

Remember the “Tiny Man” fallacy? You don’t have a tiny pilot inside your head fighting the world. You have an organism reacting to an environment.

If you do not create and control your environment, it creates and controls you.

To practice free will, you must identify your “Hostile Environments.” Is it the phone next to your bed that triggers an hour of doom-scrolling before you even wake up? Is it the smell of the bakery that overrides your diet? Is it the specific tone of voice your partner uses?

Awareness is the prerequisite for choice. You cannot surf a wave you don’t see coming.

Read more: Understanding Yourself – Roadmap to a More Authentic YOU

Step 2: Pause

Here’s the thing. Seeing the trigger is not enough on its own.

As discussed, you don’t have direct control over your impulses or bodily functions. You cannot command your heart to stop racing—nor yourself not to desire a donut.

However, you DO have indirect control.

Think of it like piloting a boat. You can’t control the wind, but you CAN adjust the sails.

You cannot command your heart to slow down, but you CAN choose to breathe slowly, which biologically forces the heart to slow down.

When anger rises, don’t try to suppress it—that’s impossible. Instead, grab the indirect lever: your breath.

In that pause, ask yourself one question (Dr. Goldsmith calls it the AIWATT question):

“Am I willing, at this time, to make the investment required to make a positive difference on this topic?”

- Am I willing? (Do I have the energy?)

- At this time? (Is this the right moment?)

- To make a positive difference? (Will arguing actually help?)

If the answer is “No,” then say nothing. Walk away.

By simply asking the question, you have engaged your prefrontal cortex and broken the deterministic chain of “Stimulus -> Reaction.”

Trivia: There is a scientific term for this phenomenon: Neuroplasticity. While the determinists are right that your brain controls you, they often forget that you can change your brain. Every time you pause, every time you choose silence over shouting, you are physically strengthening new neural pathways.

In light of this, you are not just ‘acting’ free; you are rewiring the machine to support your freedom.

Read more: 45 Mindfulness Questions for Daily Clarity

Step 3: Choose your “battle”

Once you have paused, it’s time to decide what to actually do. In other words, to “choose your battle”.

Overall, our decisions can be categorized into a “Wheel of Change” as follows:

- Create: What new positive behaviors do I need to start? (e.g., “I will start writing every morning“) .

- Preserve: What works well that I need to keep? (e.g., “I will stay kind to my children“) .

- Eliminate: What negative habits must go? (e.g., “I will stop checking emails at dinner“) .

- Accept: What must I make peace with? (e.g., “I accept that my boss is difficult and will not change“) .

Often, the highest form of free will isn’t fighting reality (Create/Eliminate); it is choosing to embrace it (Accept).

It is looking at the traffic jam, taking a deep breath, and saying, “I choose to be here, because I am here.”

Read more: Self-coaching – The Art of Being Your Own Coach

The courage to be authentic

If practicing mindfulness gives us the “Space,” the next question is: What do we put in it?

This brings us back to the haunting “dizziness” we talked about previously. As discussed, while total freedom is heavy, it is also the only thing that makes love, goodness, and joy possible.

Authenticity is the flip side of the free will coin. If we are not fully determined by a biological or social script, then we are free—and obligated—to write our own lines.

The “mask” of bad faith

Most of us, however, are terrified of writing our own lines. It is, indeed, much safer to read off a teleprompter.

Jean-Paul Sartre called this “Bad Faith”—lying to ourselves to avoid the burden of choice. We say things like, “I have to go to this party,” or “I have to keep this job because of the stability”.

But as Sartre pointed out, that is never strictly true. You don’t have to do anything. You are choosing to value stability over adventure, or social peace over honesty.

When we say “I have no choice,” we are putting on a social mask to feel safe. We play the role of the “Good Employee” or the “Nice Neighbor” so we don’t have to face the risk of being a real person.

Free will is the tool that allows us to strip away this fluff—the deception and the rituals—and become who we actually are.

Read more: The Curated Self – Why Authenticity on Social Media is Impossible

Being “wrong” for the “right” reasons

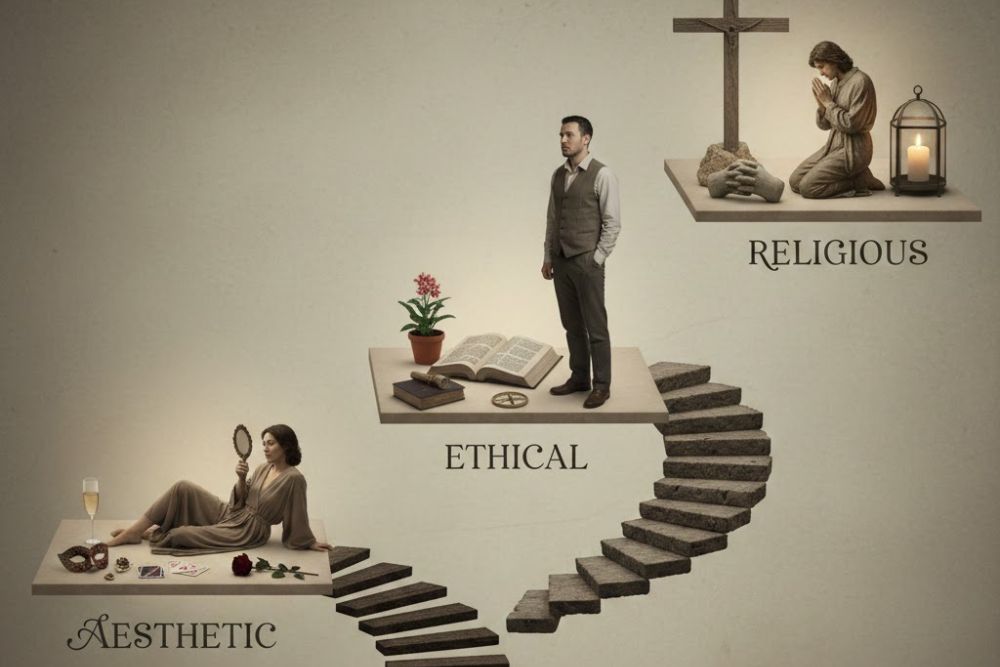

How do we break the script? I believe we can do it by looking back to Kierkegaard, who described life as being comprised of 3 stages:

- The Aesthetic Stage: Driven by pleasure, novelty, and sensory gratification. The aesthete avoids commitment to escape boredom, yet his pursuit of the “moment” eventually leads to the despair of a meaningless, fragmented existence.

- The Ethical Stage: Reached by choosing responsibility and universal moral laws. The individual finds purpose through duty, citizenship, and consistent social roles. However, reason and social norms alone cannot resolve the conflict between our finite nature and our “longing for the Infinite.”

- The Religious Stage: The highest stage, defined by a direct, singular relationship with the Absolute. It requires a leap beyond reason into “the Absurd.” Here, one transcends universal ethics to follow the Divine’s specific command, achieving true authenticity and overcoming despair through infinite passion.

Most of us live in the Ethical Stage, where we follow the “Universal Rules”—what society says is good, successful, and proper. While it is safe (and grants us reputation), it also leads to despair because you realize you are just a carbon copy of everyone else.

To become an individual, you have to leap into a Subjective Truth—a truth that is right for you, even if you cannot prove it to the “System”.

Speaking of which, I remember a time in my own career when I faced the exact same situation.

Back in the day, I created a local website for a company I worked for. I did it entirely on my own, without informing the headquarter’s team.

From the perspective of the “System” (the corporate structure), my decision seemed like an act of defiance. A “wrong” choice.

But I wasn’t doing it to be a rebel. I was acting out of honesty.

I truly believed that what I was doing addressed the real needs of the people we served—needs that the “System” was ignoring.

I had to choose between being a “Good Employee” (following the rules) and being an “Authentic Person” (following the truth).

And I chose the truth.

Now looking back at that moment, I cannot help but realize that quite often, authenticity looks like “being wrong” to the outside world. (though I have to admit if I could do it again, I would try to be more skillful in my approach)

At the point where the road swings off (and where that is cannot be stated objectively, since it is precisely subjectivity), objective knowledge is suspended. Objectively he then has only uncertainty, but this is precisely what intensifies the infinite passion of inwardness, and truth is precisely the daring venture of choosing the objective uncertainty with the passion of the infinite.

Søren Kierkegaard

The choice to rise above circumstances

Authenticity isn’t always about grand gestures or career risks. (like my decision to build the above-mentioned local website—or to quit the corporate world two years ago) Sometimes, it happens in the corners of our personal lives.

For example, I recently found myself visiting my sister—who was navigating the incredibly demanding reality of caring for a newborn while juggling housework and a high-pressure job.

The immense stress took its toll. Many times, she would burst into anger or frustration, saying things that seemed, in the moment, completely irrational and unfair.

In those heated moments, I found myself at a crossroads.

The “determined” reaction—the logical, Tit-for-Tat response—would have been to get angry back. To defend my ego. To point out that she was being unreasonable.

But then there was the “Authentic” choice.

I realized I could choose to remain calm. I could choose to offer a silent, supportive presence, even though it felt unfair to be the “punching bag”.

While the first choice (anger) felt justified, I knew it would only escalate the conflict. On the other hand, the second one (silence) preserved our relationship and gave her space to decompress.

That silence was my “Rock.” (to quote Camus) I chose to respond with compassion rather than hatred. To embrace the absurdity of loving someone when they are being unlovable.

In that moment, I was claiming back my own sense of agency. I was choosing to be a decent human being, regardless of the circumstances.

In the midst of winter, I found there was, within me, an invincible summer. And that makes me happy. For it says that no matter how hard the world pushes against me, within me, there’s something stronger – something better, pushing right back.

Albert Camus

The cost of courage

The opposite of courage in our society is not cowardice, it is conformity.

Rollo May

Let’s be clear: It’s extremely hard to be authentic.

To build the website knowing that you may face the “wrath” of the headquarter later, to stay silent when you want to scream—that requires a great deal of courage.

However, remember this: authenticity is NOT about the Ego. (“Look at how special I am!”) It is about Responsibility.

Sartre once talked about his philosophy of bad faith by describing a waiter who plays the role of a “waiter” a little too perfectly—his movements are too precise, too eager. He is acting like a waiter because he is afraid to just be a man.

When you act authentically—whether it’s breaking a corporate rule for a reason you believe in, or swallowing your pride for your sister—you aren’t performing. You aren’t playing a role.

You are responding to reality as it is, without the mask.

Read more: Ikigai (生き甲斐) – Finding Your ‘Reason for Being’

Compassion

We have spent a lot of time talking about your mind, your choices, and your authenticity. That said, unless you live on a deserted island, you are going to bump into other people.

And other people—with their confusing choices, frustrating habits, and occasional cruelty—are often the hardest part of the free will puzzle.

This brings us to a grim question: Does your belief about free will make you a Judge, or does it make you a Sage?

The Judge, the Cynic & the Sage

The debate about personal agency, as I found out, tends to reveal more about our egos than the truth of the universe.

If we cling too tightly to Absolute Free Will, we risk becoming the Arrogant Judge. We look at the poor, the addicted, or the struggling and say, “You chose this.” We become blind to the “hand of cards” they were dealt—their trauma, poverty, biology, etc. We lack empathy because we assume everyone has the same strength we do.

On the other hand, if we cling too tightly to Absolute Determinism, we risk becoming the Cold Cynic. We look at human struggle and see only “biological errors” or “chemical reactions”. We analyze people like lab rats, stripping them of their mystery and dignity.

The wisest choice is to walk the Middle Way—the path of the Sage. The Sage understands the paradox: People feel free, but they are also heavily conditioned by forces they did not choose. As such, he uses this knowledge to forgive, not to condemn.

The strategy of Asymmetry

The fault of others is easily perceived, but that of oneself is difficult to perceive; a man winnows the faults of others like chaff, but his own fault he conceals, as a cheat conceals an unlucky throw of the die.

Dhammapada, Verse 252

How do we practice this Middle Way in real life?

It’s tricky, but I believe it’s completely possible if we adopt a strategy of Asymmetry—i.e. a pragmatic “Double Standard” for living:

- Treat Yourself as a Free Agent (Libertarianism): When you make a mistake, own it. Do not hide behind “My brain made me do it.” You have access to your own “Space” (mindfulness), so you are responsible for using it.

- Treat Others as Determined (Determinism): When someone else hurts you, assume they are acting under the weight of their history, trauma, and biology. You cannot see their “Space,” so you must have compassion for their “Conditions”.

This approach maximizes your own growth (Self-Responsibility) without compromising social harmony (Compassion).

How we live our life affects everything. So we must think, How have we lived our life so that that young man… has been able to become a rapist? … The family into which [he] was born has been stuck in miserable poverty for many generations. … At thirteen years old he had to accompany his father on the boat… He had no resources of understanding and love.

If we had a gun we could shoot that young man… but would it not have been better to help him to understand and to love?

Last night on the shores of Thailand hundreds of babies were born… If those children are not properly cared for… some of them will become pirates. Whose fault is that? It is OUR fault… We cannot blame only that young man.

If I had been born a poor child who was never educated… I could have become a pirate. … Who is that pirate? He could be me…

All the suffering of living beings is our own suffering. We have to see that we are they and they are us. When we see their suffering, an arrow of compassion and love enters our hearts.

Thich Nhat Hanh, ‘No Death No Fear’

Be aware of your own ego

In his book What got you here won’t get you there, Dr. Goldsmith shares a personal story about his retreat in Plum Village as follows:

Our guide was the Vietnamese Buddhist monk, Thich Nhat Hanh. Each day Thich Nhat Hanh encouraged us to meditate on a variety of topics.

One day the topic was anger. He asked us to think of a time in our lives when we had become angry and lost control. Then he asked us to analyze who was responsible for our unattractive behavior.

I thought of my daughter Kelly when she was in her teens. She came home wearing a large brightly colored article of jewelry called a navel ring. These are common among the younger set, along with tattoos in hard-to-reach places of the human anatomy. There is no use having a navel ring if people can’t see it! So Kelly had also acquired a heroically skimpy outfit designed to highlight the navel ring. (and nearly everything else about her abdomen)

A navel ring on a daughter is one of those moments that truly tests a father’s tolerance and love. But for me it was a little more complicated, I guess. I reacted with something less than enthusiasm. In fact, I devolved into a raving, ranting caricature of an angry father.

As I meditated on this event in the quiet confines of the monastery, I wondered, “What was I thinking about?”

I realized that my first thought was that someone would see my daughter and think, “What a cheap-looking, trashy kid! Who are her parents?”

My second thought was worse. What if one of my friends saw her and thought, “I can’t believe Marshall allows his kid to parade around town like that.”

Who was I concerned about in this case? Kelly or me? Was the bigger problem her navel ring or my ego?

If I had to do it over again, I would still suggest she lose the navel ring. (One week of enlightenment in France is good, but not that good!) However, I would stop reacting with anger and making a fool out of myself.

From a Deterministic view, Goldsmith’s anger wasn’t a “choice”—it was a conditioned response driven by social status anxiety and paternal instinct. Most parents would stay stuck here, blaming the child (“You are rebellious!”).

But as he later realized, the bigger problem wasn’t his daughter’s navel ring; it was his own ego.

This is where the power of the Asymmetrical view comes in. You treat yourself responsible for your own ego, while understanding that your loved one is just being driven by the environment they live in.

Deconstructing “Evil”

While doing my own research on the topic of free will, I came across a Reddit thread in which there is a philosophical argument that goes like this:

“I don’t care if someone murders a child, it’s not their fault – something is wrong in their brain to do that and if we don’t want innocent people to get hurt we need to solve the root problem instead of reacting angrily at “criminals”/ those who deviate from or who struggle to do prosocial behaviors.”

This is difficult to swallow. But I myself believe that compassion does not necessarily mean approval.

We do not have to agree with the crime to understand the criminal.

A criminal, after all, is not an isolated “monster” acting in a vacuum; they are, many times, the result of interconnected causes—poverty, abuse, brain injury, or untreated mental illness.

As the Japanese author Shusaku Endo wrote:

“There is no such thing in the world as absolute evil or absolute good. There is good to be found within evil, and plenty of evil to be found within the good.“

The world is torn apart between good and evil, fate and freedom. It’s a constant cycle that knows no end.

We must stop trying to be the “They”—the crowd that points fingers—and focus on being the “Light”.

We change the world not by judging the darkness, but by understanding what caused it.

Read more: Spiritual Crisis – Finding Light in the “Dark Night of the Soul”

The final test

It doesn’t matter which side you are on in this debate. At the end of the day, everything boils down to one simple test.

Ask yourself: Does your stance on Free Will make you a better person?

If your belief in Free Will makes you arrogant, or your belief in Determinism makes you cruel, you have failed.

To quote the Dalai Lama:

“The best religion is one that gets you closest to God. It is the one that makes you a better person. I am not interested, my friend, about your religion… What really is important to me is your behavior in front of your peers, family, work, community and in front of the world.”

If you replace “religion” with “philosophy” or “ideology”, you will see where you should be heading.

The “Mystery” of Free Will

A mystery is a problem that encroaches upon its own data, that invades the data and thereby transcends itself as a simple problem.

Gabriel Marcel

By now, I suppose you should have realized (if you are honest with yourself) that trying to come up with a definitive answer to the problem of “free will” is just like the boy on the beach—trying to pour the infinite ocean of existence into the seashell of our logic. A futile effort after all.

At the end of the day, the math doesn’t settle. We are still left with the “Scientific Siege” on one side, telling us we are biological machines, and the “Existential Feeling” on the other, screaming that we are free. The paradox remains.

But perhaps we can view this lack of closure not as a failure, but a doorway. A “mystery.”

To quote the mystic Richard Rohr:

“Mystery is not something that you cannot understand, but it is something that is endlessly understandable!”

A puzzle is something you solve and put away. A mystery, on the other hand, is something you enter and live within.

Uncertainty is a blessing

To listen to Being, we must silence the noise of certainty.

Martin Heidegger

There is a reason why films like Minority Report or the series Devs haunt us. They present a world where the future is perfectly predicted—where Determinism is a known fact. In those worlds, characters often fight desperately to break the prediction.

Why? Because if we truly knew the script, we would cease to be “living”; we would just be reciting lines.

The uncertainty we fear is actually the oxygen of our existence.

If the Universe gave us clear, booming orders, we would be slaves. Its silence or indifference, therefore, is necessary for us to flourish.

It is the prerequisite for the “Leap of Faith” those like Kierkegaard talked about.

It was in the silence that I heard Your voice.

Father Rodriguez, Silence (2016)

A call to action

From here, we return to the “Middle Way” we have discussed above. Think of your life as a Feedback Loop.

- The Input is the world giving you your circumstances—your genetics, your history, your traffic jams. That is your Karma.

- The Output is your conscious response—your attitude, your kindness, your refusal to give in to hate. That is your Dharma (Duty).

The world may look like a broken, deterministic machine. It may be flavorless and dark. But that doesn’t mean we have to give in to despair.

We can become the “Salt” that adds the flavor of agency. The “Light” that adds the direction of meaning.

We can act as the bridge between the cold laws of physics and the warmth of human love.

We can despair of the meaning of life in general, but not of the particular forms that it takes; we can despair of existence, for we have no power over it, but not of history, where the individual can do everything.

Albert Camus

Free Will Quotes

Check out a full list of quotes about free will here!

Frequently Asked Questions About Free Will

Does science prove free will is an illusion?

While neuroscience (like the Libet experiment) and physics suggest our actions are influenced by biological and atomic causes, they do not necessarily disprove agency. They simply prove that we are not 100% independent of our environment.

As discussed above, agency is still possible within those biological constraints.

What is the difference between free will and determinism?

Determinism is the view that every event, including human action, is the inevitable result of preceding causes (like a falling domino). On the other hand, Total Free Will (Libertarianism) is the view that humans can initiate actions independent of those causes.

The “Middle Way” (Compatibilism) suggests these two can coexist.

Does God allow free will?

This is a classic theological debate. In many traditions, such as the story of St. Augustine mentioned earlier, it is said that humans are given free will to allow for genuine love and morality.

If every action is controlled by an external force (God/ the Universe, etc.), we would be robots, and concepts like “goodness” or “sin” would lose their meaning.

How can I practice free will in daily life?

Free will is best practiced through mindfulness. By creating a “space” between a stimulus (trigger) and your response, you move from being a reactive machine to a conscious agent.

Final Thoughts

So here we are: the end! Or should I say, the beginning.

It’s time for us to put the reflections so far into real life. To adopt the stance of Socrates: regarding the metaphysics of the universe, “I don’t know for sure“. But regarding one’s own life, “I know what I must do.”

Close your laptop. Put down your phone. Look at the people around you.

You did not choose them, and you did not choose the person you were when you woke up this morning.

But you are here now. The cards have been dealt.

Play them beautifully.

Waste no more time arguing what a good man should be. Be one.

Marcus Aurelius

Other resources you might be interested in:

- Spiritual Purpose: The Quest for the Soul’s Calling

- Memento Mori: A Reminder of Life’s Impermanence & How to Live the Right Way

- Life Management: How to Design a Life You Love

- Choosing Your Life: From ‘Drifting’ to ‘Defining’

Let’s Tread the Path Together, Shall We?