Have you ever walked into a room—perhaps a Monday morning meeting, a family gathering, or even a church service—and felt a sudden, heavy exhaustion wash over you? Not physical tiredness – but the exhaustion of performance.

You check your face in the mirror/ reflection of your phone screen. You adjust your smile. You prepare the “correct” opinions. You walk in, shake hands, and say the lines the script requires.

But deeply, a voice in the back of your mind whispers: This isn’t me. I am just playing a character.

Most people refer to this as “imposter syndrome” or “social fatigue,” but the existentialist philosophers gave it a sharper, more haunting name. They called it bad faith.

Highlights

- Living in bad faith (Mauvaise foi) is the act of lying to yourself to escape the anxiety of being free. Essentially, it is choosing the comfort of a “role” over the responsibility of being human.

- We do it by denying our freedom (“I have no choice”) or reality (“This isn’t really happening”), turning ourselves into objects rather than subjects.

- Living in bad faith is sure to lead to resentment, fragility (a “house on sand”), and the inability to truly connect with or love others.

- Authenticity isn’t selfish individualism. It requires trusting your intuition (the Leap of Faith), embracing uncertainty, and realizing that your freedom is interconnected with the freedom of others (Interbeing).

What is Bad Faith?

More than just being “fake” to impress others, bad faith involves something far more subtle and dangerous. It is the act of lying to yourself so convincingly that you actually start to believe the lie. It happens when you forget who you are – because you have become so good at being who the world wants you to be.

While the term was popularized by the secular philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre in his magnum opus Being and Nothingness (he called it mauvaise foi), the concept didn’t start with him. In fact, it has deep spiritual roots – tracing back to the Danish theologian Søren Kierkegaard.

At his time, Kierkegaard, a deeply devout Christian, was warning against losing oneself in “The Crowd”—the comfortable, numb state where we just do what everyone else does to avoid the anxiety of making our own choices.

The crowd is untruth.

Søren Kierkegaard

Based on Kierkegaard’s idea, Sartre took it further, defining bad faith as a form of self-deception where we deny our own freedom.

The paradox of bad faith

To lie to yourself, you have to be two people at once. You must be the Deceiver (who knows the truth) and the Deceived (who believes the lie).

- The Truth: You are free. You have choices. You are responsible for your life.

- The Lie (Bad Faith): “I have no choice. That’s just the way the world is. I have to do this job. I have to stay in this relationship. I am a victim of circumstance.”

Othello and Iago – a common visual depiction of living in bad faith

Why does it matter?

Some of you may ask: Why care about it? Why not just play the role if it keeps the peace?

Because living in bad faith is a spiritual sedative. It numbs you.

As the religious existentialist Gabriel Marcel has argued, when we reduce ourselves to a function or a role, we stop being a “Who” and become a “What.” We become things.

The Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky—who wrestled with these themes through a Christian lens—gave us perhaps the most chilling warning about where this path leads. In The Brothers Karamazov, the Elder Zosima says:

“Above all, do not lie to yourself. A man who lies to himself and listens to his own lie comes to a point where he does not discern any truth either in himself or anywhere around him, and thus falls into disrespect towards himself and others. Not respecting anyone, he ceases to love.”

This is the danger of bad faith. More than just academic philosophy, it is about the ability to love.

If you are not real, you cannot truly love, and you cannot be truly loved. You are just a ghost haunting your own life.

The Philosophy of Bad Faith

How is it possible that a rational human being can manage to trick their own mind?

Sartre addressed this question with two famous examples. On the surface, they might seem like simple observational sketches, and yet they reveal the precise mechanics of how we trade our freedom for comfort.

Example #1: The waiter who is a little too perfect

Imagine you are sitting in a café in Paris. You watch a waiter moving between the tables.

His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step that is a little too eager. His voice is overly solicitous; his eyes are intensely focused. He is balancing his tray with the kind of reckless perfection of a tightrope walker.

As pointed out by Sartre, this man is “playing” at being a waiter.

He isn’t just doing a job; he is trying to become the job. He is trying to merge himself completely with the role of “The Waiter” – so that he doesn’t have to deal with the messy, anxious reality of being a human being who has worries, dreams, doubts, or a life outside that café.

If he is just a “Waiter”—an object, a function, a machine that delivers coffee—then he is safe. Objects don’t have existential crises. Robots don’t feel anxiety.

By trapping himself in the definition of his job, he is living in bad faith.

Example #2: The “distracted” date

The second example Sartre proposed is about a woman on a first date.

She knows the man’s compliments have a sexual intention. She knows that sooner or later, she will have to make a decision: accept his advances – or reject them. Both choices require agency; both carry a risk.

Then, he takes her hand.

To pull her hand away would be a rejection (a decisive action). To squeeze his hand back would be consent (also a decisive action). She wants neither responsibility.

So, she leaves her hand there. She pretends she doesn’t notice it. She continues talking about high-minded intellectual topics, divorcing her mind from her body. She treats her own hand as a “thing”—an inert object resting on the table—disconnected from her will.

She is pretending that she is NOT free to choose, effectively saying, “It’s not my fault; this is just happening to me.“

Examples of bad faith philosophy

The two modes of Self

The above-mentioned examples reveal the core conflict. Existentialists argue that we are always juggling two sides of our reality:

- Facticity (The Facts): The concrete details of your life—your height, past, job title, bank account, etc.

- Transcendence (The Freedom): Your ability to interpret those facts, to change, to dream, and to be more than just your labels.

Bad faith happens when we deny one to hide in the other.

- The Waiter denies his Transcendence. He pretends he is only his Facticity (his job title). “I am just a waiter, that’s all I am.”

- The Woman denies her Facticity. She pretends her physical situation isn’t happening so she can float in pure Transcendence.

We do this every day. When we say, “I yelled at my kids because I’m Irish and we have hot tempers,” we are using Facticity (genetics/culture) as an excuse to deny our Transcendence (our freedom to choose patience).

We turn ourselves into objects to avoid the heavy lifting of being human.

The Many Faces of Bad Faith in Life

Sartre’s examples were from 1940s Paris, but human nature hasn’t changed since then. We still play roles. We still hide. We are still living in bad faith.

I myself see this “masquerade” everywhere—in the boardrooms where I used to work and, heartbreakingly, even in the pews of the church I attend.

The corporate “nodders”

I remember sitting in online meetings at one of my previous companies. These calls would drag on for hours—sometimes half a day—focused mostly on headquarters’ strategies that had little to do with the reality in local branches.

Looking at the grid of faces on the screen, I saw a masterclass in bad faith.

Colleagues who I knew were intelligent, critical thinkers would suddenly transform. They would nod enthusiastically at everything the CEO said. They would unmute only to offer cryptic, safe compliments: “You are the best, sir,” or “Great initiative.” They played the role of the “Good Employee” to perfection.

But the moment the meeting ended, the mask dropped. The private chats lit up. The same people who just praised the CEO’s “humility” were now mocking his ego. They despised the meetings, yet they participated in the charade with total commitment.

Why? Because it was easier.

To speak up, to challenge the strategy, or even to ask a real question would require agency. It would risk friction.

By reducing themselves to nodding bobbleheads, they survived the workday, but they sacrificed a piece of their dignity. They chose to be “things” that agree, rather than people who think.

The spiritual “costume”

As a Christian myself, this next example hits close to home. You would hope that religious communities would be the antidote to bad faith—places of radical honesty.

Instead, as I figured, they are often where the masks are thickest.

I see it in my own local Catholic community. There are those who treat their faith NOT as an internal transformation, but as a public performance.

I have watched neighbors recite the Rosary loudly in the street so others can see their piety, only to turn around and scream curses at their spouses or gossip viciously about “outsiders” moments later.

I see business owners who never miss a Sunday mass – but continue to sell low-quality products at inflated prices on Monday.

I see families who treat Christmas not as a solemn celebration of the Incarnation, but as a cultural festival for selfies and social signaling.

This is the “Crowd” that Kierkegaard warned us about.

They use God as a tool to enforce rules on others (“That is a sin,” “The world is broken”) while refusing to look inward. They hide behind the “role” of the Pious Believer.

It is a terrifying form of bad faith – because it uses the Divine as a shield against the truth.

As long as they attend the rituals and say the right words, they don’t have to face the difficult responsibility of actually loving their neighbor. Instead, they can just indulge in petty feuds and badmouth those who marry outside the faith.

Most religious people, as far as I can see, only follow rules and seek external validation/ glory/ public recognition – instead of reflecting in silence and changing themselves. A very shallow approach to spirituality, I have to say.

No wonder they cannot find God. No wonder they keep acting unethically – out of bad faith.

I pray but I am lost. Am I just praying to silence?

Father Rodrigues, “Silence” (2016)

The curated avatar

And then, of course, there is the most modern trap of all: the Digital Self.

Social media is a factory for bad faith. We create a profile—a curated essence of who we want to be. We post the successes, the “hustle,” the happy relationships.

Eventually, we become enslaved to the avatar we created. We stop making choices based on what we want – and start basing our decisions on what “The Character” would do.

We deny our sadness – because “The Character” is happy. We deny our struggles – because “The Character” is successful.

We become the waiter, but instead of a tray, we are balancing a smartphone, terrified that if we drop the act, we will cease to exist.

Read more: Are You Living or Just Existing? Let’s Find Out!

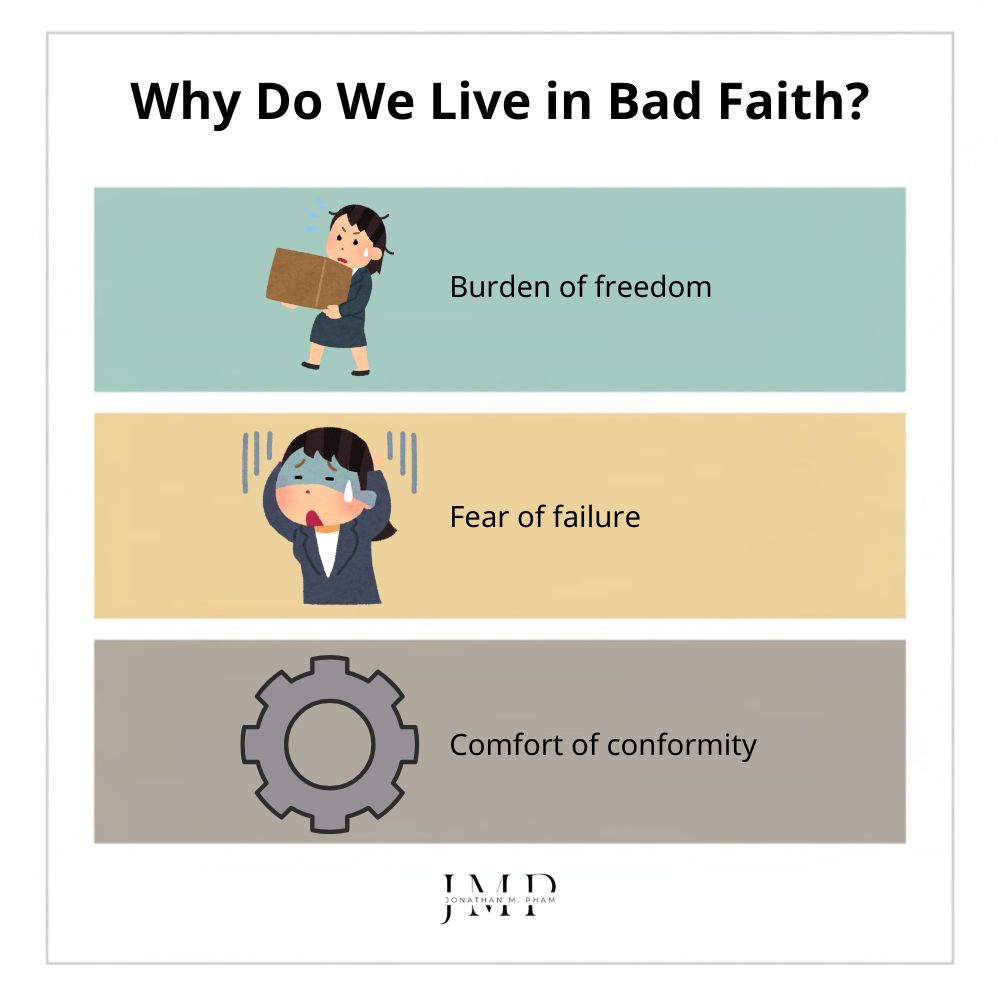

Why Do We Live in Bad Faith?

If living in bad faith is so draining—if it turns us into “nodding cogs” and “performative believers”—why do we do it? Why do the vast majority of us choose the mask over reality?

The simple answer is that authenticity (the opposite of bad faith) is terrifying.

The burden of freedom

No doubt I do act in ‘bad faith’ when I deliberately avoid facing an honest decision and follow the conventional pattern of behavior in order to be spared the anxiety that comes when one is… thrown into seventy thousand fathoms.

John Macquarrie

Sartre declared that we are “condemned to be free.” According to him, most of us tend to think of freedom as a happy, light thing. But existential freedom is a heavy weight.

If you acknowledge that you are free, you must also acknowledge that you are responsible.

- If you are unhappy in your job, and you acknowledge you are free, you have to admit that you are choosing to stay.

- If you are unfulfilled in your relationships, and you acknowledge you are free, you have to admit that you are maintaining the status quo.

This realization produces Angst. To escape anxiety, we turn to bad faith. We tell ourselves, “I have no choice,” because if we have no choice, we cannot be blamed for the outcome.

Bad faith, in other words, is a shelter from the burden of responsibility.

Fear of failure: The “life lie” many succumb to

If your lifestyle were determined by other people or your environment, it would certainly be possible to shift responsibility. But we choose our lifestyles ourselves. It’s clear where the responsibility lies.

Ichiro Kishimi, “The Courage to Be Disliked”

Reflecting on the idea somehow reminds me of Alfred Adler’s theory of Individual Psychology. While Adler and Sartre approached life from different angles, I see that they agreed on one uncomfortable truth: We are not victims of our past; we are the creators of our present.

Adler argued that many of us live by a “Life Lie.” We take advantage of our circumstances—trauma, upbringing, “shyness”—as a shield.

- The Excuse: “I can’t pursue my passion because my parents were strict/because the economy is bad.”

- The Hidden Benefit: As long as I have this excuse, I never have to test my abilities. I can preserve my ego. If I try and fail, I am a failure. But if I don’t try because “I can’t,” I remain safe.

In light of this, we live in bad faith – because it protects our ego from the risk of failure.

The comfort of conformity

Nothing in the world is harder than speaking the truth and nothing easier than flattery. If there’s the hundredth part of a false note in speaking the truth, it leads to a discord, and that leads to trouble. But if all, to the last note, is false in flattery, it is just as agreeable, and is heard not without satisfaction. It may be a coarse satisfaction, but still a satisfaction. And however coarse the flattery, at least half will be sure to seem true. That’s so for all stages of development and classes of society.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, ‘Crime and Punishment’

The world, after all, is eager to hand us a script. We are surrounded by systems designed to remove the burden of thinking from our shoulders.

- The Corporate Ladder: It tells you exactly what “success” looks like. You don’t have to define your own values; you just have to hit the next KPI.

- Dogmatic Religion: As I mentioned earlier, rigid religious systems often sell “fake certainty.” They provide a checklist for salvation/ liberation – so you don’t have to wrestle with the mystery of the Divine on your own.

- “Common Sense”: The pressure to just be “normal.”

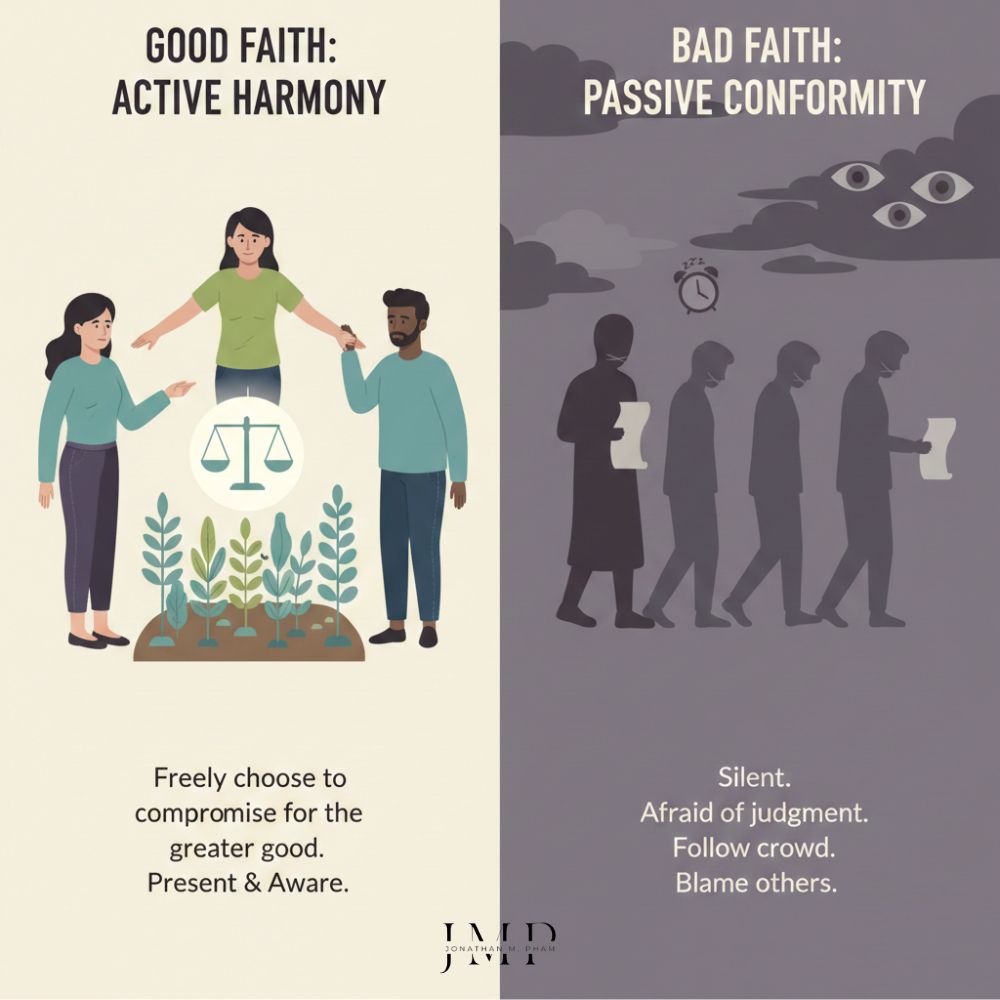

A note on harmony vs. conformity

It is important here to make a distinction. Choosing to fit in is NOT always bad faith.

In many Eastern traditions, social harmony (the Japanese call it Wa/ 和み) is seen as a great virtue. That being said, I believe there is a massive difference between Active Harmony and Passive Conformity.

- Active Harmony (Good Faith): You assess the situation and freely choose to compromise your immediate desires for the greater good of the community. In other words, you are present and aware.

- Passive Conformity (Bad Faith): You stay silent because you are afraid of being judged. You follow the crowd – because you don’t know who you are without them.

Difference between good faith and bad faith in existentialism

Most of us aren’t ACTUALLY valuing harmony; we are just sleepwalking.

Like the student who asked Sartre for advice on whether to join the war or stay with his mother, we, deep down, only want someone else—a teacher, a boss, a scripture, or a societal norm—to tell us what to do, so that if it goes wrong, we can blame them.

The Consequences of Living in Bad Faith

So, we wear the mask. We nod in the meetings, we play the perfect role in our communities, and we suppress the inner voice that asks, “Is this it?”

For a while, bad faith works. It feels safe. It keeps the peace. But the thing is, you cannot establish a sturdy structure on a shifting foundation.

When you make bad faith the basis of your life, you are, essentially, building a “House on Sand”. (don’t get me wrong – it’s not an exclusively religious idea, as I’m going to share with you)

The crisis of meaning

When your identity is tied to an external role—”I am a Success because I have this job” or “I am Good because I follow these rules”—you are handing your self-worth to something you cannot control.

I saw this constantly in the corporate world. I knew men and women who had followed the “script” perfectly. They had the title, the salary, and the reputation.

But the moment the market shifted – and they were laid off, or the moment they retired, they didn’t just lose a paycheck; they lost their existence.

They fell into a deep depression not because they had just lost a job – but because they had lost the “Self” they had pretended to be for 30 years.

This is the root of the stereotypical Mid-Life Crisis. Out of social expectations and the desire for recognition, you may assume you want a sports car. But the moment the “Bad Faith” dam breaks, you realize you have spent half your life climbing a ladder that meant nothing to you.

In other words, you built a life that looks perfect on paper – but feels empty within.

Read more: Spiritual Crisis – Finding Light in the “Dark Night of the Soul”

The risk of nihilism & resentment

A man who lies to himself is often the first to take offense. It sometimes feels very good to take offense, doesn’t it? And surely he knows that no one has offended him, and that he himself has invented the offense and told lies just for the beauty of it, that he has exaggerated for the sake of effect, that he has picked up on a word and made a mountain out of a pea–he knows all of that, and still he is the first to take offense, he likes feeling offended, it gives him great pleasure, and thus he reaches the point of real hostility.

Fyodor Dostoevsky, “The Brothers Karamazov”

Dostoevsky once warned that the man who lies to himself eventually “takes offense” at everything. Why?

Because living in bad faith creates a deep, simmering resentment.

Think of the “Martyr” archetype we see in so many families or workplaces. This is the person who says, “I sacrificed everything for you! I did what I was supposed to do!”

- The Secular Example: The employee who stays late every night NOT out of passion, but out of fear/obligation, and then seethes with anger when nobody praises them for it.

- The Religious Example: The “Elder Brother” in the Prodigal Son story. He followed all the rules, NOT out of love for the Father, but out of duty. When the rebellious son returns and is celebrated, the Elder Brother becomes furious.

These are the consequences of inauthenticity. When you force yourself to act “nice” or “dutiful” when you don’t MEAN it, you aren’t actually being kind. You are only creating a transaction, thinking, “I am suffering through this role, so the world owes me a reward.”

And obviously, when the world doesn’t pay up, that hidden gap between your true feelings and your actions fills with bitterness.

Read more: Nihilism vs Existentialism vs Absurdism – A Journey Into the Abyss

The loss of connection

Mundus vult decipi: the world wants to be deceived. The truth is too complex and frightening; the taste for the truth is an acquired taste that few acquire.

Martin Buber, “I and Thou”

Perhaps the saddest consequence, as mentioned above, is that bad faith makes true love impossible.

To love someone, you must be a “Thou”—a real, vulnerable subject—connecting with another “Thou.” But when you are in bad faith, you have turned yourself into an object (a role). And objects cannot love; they can only be used.

If I am playing the role of “The Strong Provider” – and I refuse to show vulnerability because it breaks character, I am not letting my spouse love me; I am letting them love my performance.

If I am playing the role of “The Perfect Christian/ Buddhist,” I cannot confess my struggles to my community.

The result is loneliness. You may be surrounded by people who applaud your performance – yet feel completely invisible.

As the psychologist Rollo May has proposed, the opposite of courage is not cowardice; it is CONFORMITY. And the price of conformity is the loss of the ability to connect deeply with another human being.

From Bad Faith to True Authenticity: Beyond “Western Individualism”

Many people, upon hearing the word “Authenticity”, would imagine a rebellious Western hero—someone who quits their job, flips off society, and moves to a cabin to do exactly what they want, whenever they want.

But this, I believe, is a deeply misguided assumption.

True existential authenticity is not the same as selfish individualism. It does not mean completely severing one’s ties to the world.

In fact, both the French existentialists and Eastern philosophers agree on this simple truth: You cannot be truly free alone.

The ethics of ambiguity

While Sartre focused on individual freedom, his partner Simone de Beauvoir took the concept further in her book The Ethics of Ambiguity – in which she argued that freedom is not a solitary activity.

“To will oneself free is also to will others free.“

Her reasoning was practical: If I treat others as objects—if I manipulate, ignore, or oppress them—I am creating a world of objects. Eventually, that world will crush me, too.

Therefore, my authenticity is inextricably linked to yours.

If you say exactly what you think without caring about others’ feelings, claiming “I’m just being real,” you aren’t being authentic; you are being a narcissist. You are denying the humanity of the person in front of you.

That is just bad faith disguised as honesty.

The interconnected self

If we take Beauvoir’s viewpoint into consideration, we will see that authenticity requires one to recognize the Interbeing nature of the self. That we do not exist in a vacuum; we “inter-are.”

To better clarify this point, I would like to bring up the Japanese concept of Oubatori (桜梅桃李), which refers to the four spring trees: Cherry, Plum, Peach, and Damson.

Each tree blooms in its own way, at its own time, with its own specific scent. The cherry blossom does not try to be a plum blossom. It does not look at the peach tree with envy. It simply is itself.

And here is the crucial part: They all grow in the same forest. They share the same soil, same air, same ecosystem.

In many cultures, people often confuse “Harmony” with “Uniformity.” We think harmony means everyone acting the same (bad faith).

But true harmony is like an orchestra: The violin must sound like a violin, and the flute must sound like a flute. If the violin tries to sound like a flute to “fit in,” the music is ruined.

A being among beings

In making our choices, we need to respect the freedom of others. I am obliged to will the freedom of others at the same time as I will my own. I cannot set my own freedom as a goal without also setting the freedom of others as a goal.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Authenticity, therefore, means accepting the responsibility of being a unique “I” while recognizing that you are always in relationship with a “Thou.”

As the existentialist Gabriel Marcel noted, that is when we move from the isolated “I” to the participative “I am a being among beings.” Or, as the Golden Rule implies across almost all major religions: The way I treat you is a reflection of who I am.

Here’s a quick comparison for you to better get the point:

- Inauthentic: “I will become a doctor because my parents want me to, even though I hate it.” (Sacrificing the Self for the Group).

- Selfish: “I will quit my job and abandon my family because I need to ‘find myself.'” (Sacrificing the Group for the Self).

- Authentic: “I realize I cannot be a good doctor because my heart isn’t in it. If I stay, I will become bitter and resentful, which hurts my patients and my family. Therefore, I will choose a path where I can truly contribute my best self to the world.”

To round it off, authenticity does not mean doing whatever you want. Rather, it is the courage to find the specific shape of your own soul so that you can fit it properly into the puzzle of the world.

When we are able to act freely, we can move away from the isolated perspective of the problematic man (“I am body only,”) to that of the participative subject (“I am a being among beings”) who is capable of interaction with others in the world.

Gabriel Marcel

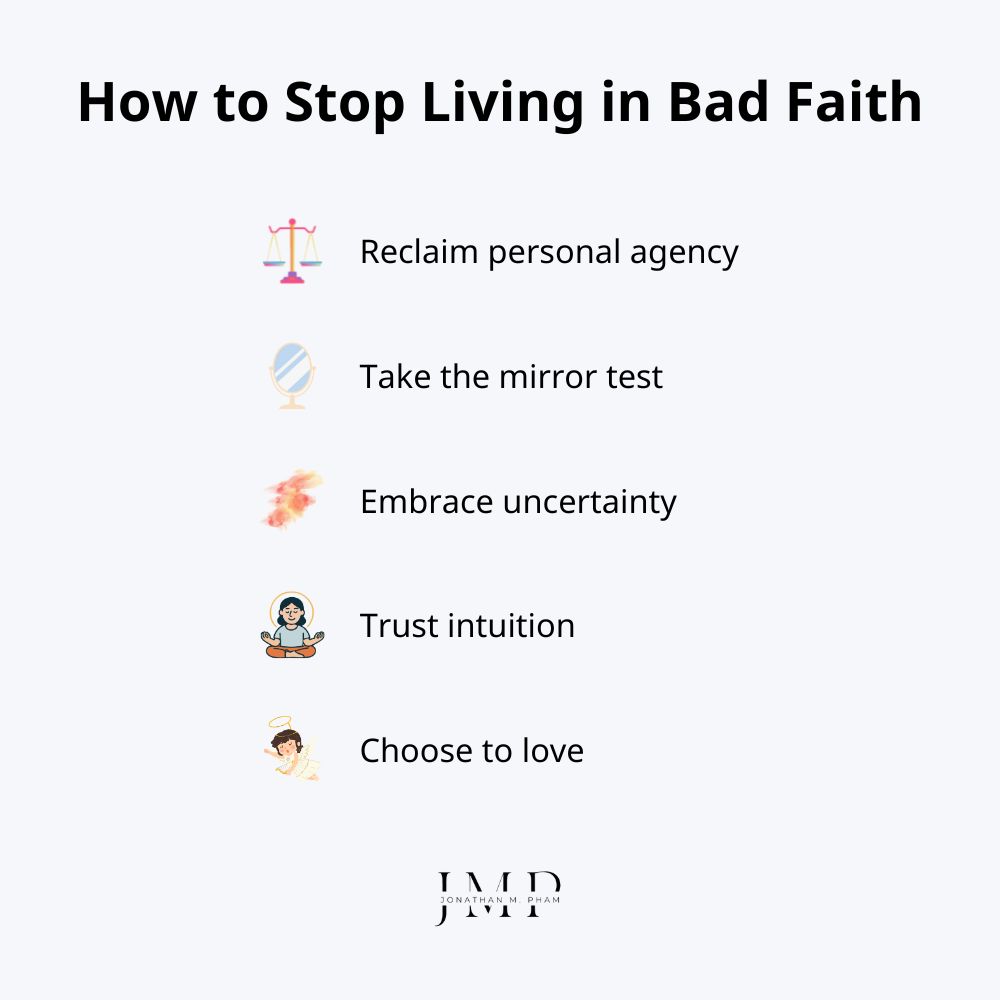

How to Stop Living in Bad Faith

Knowing you are in bad faith is one thing; but climbing out of it is another.

It requires a kind of spiritual violence against your own comfort – that you stop sleepwalking and start living.

Reclaim personal agency

Our tendency is to constantly come up with excuses to deny our own freedom. We say, “I have to go to this meeting,” “I have to stay in this marriage,” or “I have to act this way because I’m an introvert.”

Every time you say “I have to,” you are pretending to be an object controlled by external forces.

If you find yourself in the same situation, try replacing “I have to” with “I choose to.”

- Old: “I have to go to this draining family dinner.” (Victim mentality).

- New: “I am choosing to go to this dinner because I value my relationship with my mother, even if the event itself is boring.”

A subtle mental shift, yet it serves as the starting point of restoring personal agency. In doing so, you remind yourself that you are NOT a leaf blowing in the wind; you are the one deciding where to land.

Even in the worst circumstances, as Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl has pointed out, we retain the ultimate freedom: the ability to choose our attitude.

Take the mirror test

Many of us take advantage of our roles to hide the emptiness within. We think, “If I am a CEO/Pastor/Mother, then I matter.”

One way to give up on this bad habit is to stand in front of a mirror (literally or metaphorically) and ask yourself: If I lost my job, my relationship, my social status, and my bank account today… who would be left standing here?

If the answer is “No one” or “I don’t know,” you have been living in bad faith. You have confused your Being with your Doing.

Authenticity begins when you can separate your soul from your resume. You are not a “waiter” or a “manager”; you are a human being currently working as one.

Read more: 200 Self-reflection Questions – Toolkit for Life Pilgrims

Bad faith questions

Embrace uncertainty

Bad faith thrives on fake certainty. It loves black-and-white answers provided by political ideologies, rigid religious dogmas, or corporate handbooks. “Just follow the rules, and you will be safe.”

However, you can overcome it by adopting the practice of healthy skepticism – i.e. thinking like a philosopher.

- When a political leader says, “This is the only way,” ask: Is it?

- When a religious leader says, “God/ Buddha wants you to do X,” ask: Does He? Or does the institution want that?

- When society says, “You must own a house to be successful,” ask: Says who?

Don’t accept the “script” without experiencing it yourself first. If the result is compassion and clarity, keep it. Otherwise, just let it go, no matter how “authoritative” the source.

Don’t go by reports, by legends, by traditions, by scripture, by logical conjecture, by inference, by analogies, by agreement through pondering views, by probability, or by the thought, ‘This contemplative is our teacher.’ When you know for yourselves that, ‘These qualities are skillful; these qualities are blameless; these qualities are praised by the wise; these qualities, when adopted & carried out, lead to welfare & to happiness’ — then you should enter & remain in them.

Kalama Sutta

Trust intuition

Eventually, logic will run out. While great for safety, it is terrible when it comes to authenticity. In most circumstances, logic will always tell you to stay in the bad faith situation because it is “secure.”

This is where you must take the Leap of Faith.

More than a religious concept, the leap of faith refers to the act of trusting your intuition over the “facts.” – when you realize, deep down, that passion often looks irrational on paper.

When I left my stable corporate career to start this blog two years ago, logic screamed at me: “You are giving up a pension. You are giving up a clear ladder. You will be a nobody.”

If I had listened to “common sense,” I would still be sitting in that office, nodding at a screen, dying a little every day. And yet, I trusted that the feeling of “wrongness” in my gut was more true than the numbers in my bank account.

To live in Good Faith, you must be willing to come up with decisions that don’t have a guaranteed outcome (provided you have carefully thought about it – I’m not promoting a YOLO lifestyle here).

You have to act NOT because you know you will succeed, but because you know you cannot live with yourself if you don’t try.

Choose to love

PHILOSOPHER: Any person can be happy from this moment onward. […] But happiness is not something one can enjoy by staying where one is.

You took the first step. You took a big step. Now, however, not only have you lost courage and let your feet come to a halt, you are trying to turn back. Do you know why?

YOUTH: You’re saying I don’t have patience.

PHILOSOPHER: No. You have not yet made the biggest choice in life. That’s all.

YOUTH: The biggest choice in life! What do I have to choose?

PHILOSOPHER: I said it earlier. It is ‘love’.

YOUTH: Hah! You expect me to get that? Please don’t try to escape into abstraction!

PHILOSOPHER: I am serious. The issues you are now experiencing all stem from the single word ‘love’. The issues you have with education, and also the issue of which life you should lead.

Ichiro Kishimi, “The Courage to Be Happy”

I cannot say this too strongly: The ultimate antidote to Bad Faith is Love.

At the end of the day, most of our problems in life are interpersonal relationship problems, and the solution is the courage to love.

Living in bad faith is a defense mechanism. We wear masks to protect ourselves from being hurt, judged, or rejected.

To love yourself means admitting you are imperfect – and refusing to hide it.

To love others means engaging with them as they are, NOT as you want them to be.

If you cannot love yourself—if you are constantly trying to be a “character”—you cannot truly believe anyone else loves you. You will always think, “They only love the mask, not me.”

Authenticity is the act of dropping the shield. It is saying to the world, to the Divine, to yourself, and to your loved ones: “Here I am. No script, no costume. Just me.“

It is terrifying, yes. But it is the only way to be truly alive.

How to stop living in bad faith

Further Resources

Bad faith quotes

More existential quotes can be found here!

Existence precedes essence.

Jean-Paul Sartre (Reminding us that we are not born with a fixed purpose; we create it through our choices.)

Man is always something more than what he knows of himself. He is not what he is simply once and for all, but is a process; he is not merely an extant life, but is, within that life, endowed with possibilities through the freedom he possesses to make of himself what he will by the activities on which he decides.

Karl Jaspers

Freedom without compassion is demoniacal. Without compassion, freedom can be self-righteous, inhuman, self-centered, and cruel.

Rollo May

A waiter can play at it, but to believe that one is a role is bad faith because we are always becoming and growing, and so to view ourselves as some kind of fixed entity is to fool ourselves. It is to be a thing — like a rock — rather than a person with intentions and projects, with a past and a future.

Skye Cleary

Who also accuse existentialism of being too gloomy, it makes me wonder if what they are really annoyed about is not its pessimism, but rather its optimism.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Books to read

Make sure to give this list of existentialism books a try too!

- Being and Nothingness by Jean-Paul Sartre (The foundational text on bad faith, though a heavy read).

- The Sickness Unto Death by Søren Kierkegaard (For the spiritual roots of despair and the self).

- The Courage to Be Happy by Ichiro Kishimi & Fumitake Koga (An accessible look at Adlerian psychology and the courage to stop living a lie).

- The Ethics of Ambiguity by Simone de Beauvoir (On why freedom requires caring for others).

Movies to watch

If you are interested, please find out my full list of recommended existential movies here!

- The Truman Show (The ultimate allegory for waking up from a constructed reality – and embracing the unknown rather than succumbing to comfortable lie).

- Revolutionary Road (The story of a couple trapped in the “Suburban Dream” and the devastating cost of living in bad faith).

- Silence (Martin Scorsese’s adaptation of Shūsaku Endō’s novel—which offers a haunting look at stripping away external religious validation to find internal truth).

Final Thoughts

Living in bad faith is an understandable action, given the world’s tendency to constantly demand we be someone else. We ALL do it.

We all have moments where we nod when we should speak, or hide behind a role because we are afraid of being honest.

But there will come a time when the cost of inauthenticity becomes too difficult to bear.

To stop living in bad faith is not to become a rebel without a cause. Rather, it is akin to becoming a Knight of Faith—a term Kierkegaard used to describe the person who lives fully in the world, enjoying the finite details of life (a good meal, a conversation, a job), but who does so with a deep, internal grounding in the Infinite. They don’t need the applause of the crowd to know who they are.

At the end of the day, stopping self-deception means taking responsibility for your own spiritual and ethical existence. It means moving from “inherited belief” to “authentic conviction.”

The Sufi mystic Rumi once wrote:

“I looked in temples, churches, and mosques. But I found the Divine within my heart.“

Whether you believe in a Creator or simply in the human spirit, the lesson is the same: You will NOT find truth in a building, a corporate handbook, or a social media algorithm. You will NOT find it by strictly obeying a set of external rules while your heart sleeps.

You have to stop looking for the answers “out there” and start listening to the voice “in here.”

Authenticity is not a static destination where you finally “find yourself” and stop changing. It is a living process. It is messy. It requires you to engage with the world, not hide from it. To bridge the gap between belief and action.

To quote the late Pope Francis:

“We cannot confine him (Christ) to a fairy tale, we cannot make him a hero of the ancient world, or think of him as a statue in a museum! … We must take action… Look for him in life, look for him in the faces of our brothers and sisters, look for him in everyday business… Look for him everywhere except in the tomb.”

To the secular seeker, this is the ultimate existential challenge: Do not search for meaning in dead things—in titles, in past glories, or in rigid labels (“the tomb”). Look for it in the living.

Look for it in the “everyday business” of being kind, of being honest, and of showing up for others without a mask.

The door is open. In fact, it always has been.

You can stay safe, playing the role of the waiter, the manager, or the perfect believer until the end of your days. Or, you can step out.

You can accept the responsibility of being a Being rather than a Thing.

The choice is yours.

Other resources you might be interested in:

- 60 Existential Questions: A Daily Toolkit to Explore Life’s Depths

- 40 Spiritual Lessons: Wisdom for Life’s Journey

- Self-leadership: The Art of Leading from Within

Let’s Tread the Path Together, Shall We?