If there is a meaning in life at all, then there must be a meaning in suffering. Suffering is an eradicable part of life, even as fate and death. Without suffering and death, human life cannot be complete.

Viktor Frankl, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been fascinated by life’s big questions. What is our purpose? Why are we here? What does it all mean? This curiosity has driven me to write extensively on these themes (as many of you who have been with me for a while may know).

Just last year, I dedicated my November-December 2024 edition to the theme of the “meaning of life“. As difficult to believe as it may seem, it’s a widely popular topic – one discussed not just in philosophy classrooms, but also in late-night coffee talks, religious gatherings, and typed into search engines by a multitude of people around the world every month.

We are, it seems, a species desperate for meaning.

And as I reflect on it, I cannot help but realize a simple truth: one cannot truly talk about the meaning of life without taking into account the meaning of suffering.

These two are inextricably linked. Suffering is an inherent part of existence. And yet, it’s a subject most of us would rather avoid – an unwanted presence we instinctively wish we could make disappear.

However, I believe that running away from it does no good. In fact, it’s only in turning around and confronting our pain head-on that we may attain authentic happiness and fulfillment.

It’s amidst our struggles that we may uncover a much deeper sense of purpose – one that can turn life to a completely new page.

Finding meaning in suffering is definitely no joke though. To be honest, I don’t think I already have enough life experiences to be called a “master” on this topic. My intention is only to act as a “facilitator” – one whose role is to encourage you to think on your own and arrive at an answer by yourself. Everyone’s journey is theirs; only by treading the path by oneself may one discover a “truth” that resonates with them.

With that spirit in mind, let us begin, shall we?

Highlights

- Suffering is an inherent part of the human condition, often manifesting as a deep spiritual and existential void that even the conveniences of modern life cannot remove.

- Our pain arises from an interplay between uncontrollable external events and our internal world of perception and choice – in other words, between what happens to us and how we respond to it.

- The key to finding meaning in suffering is not to get trapped in the question of “Why?” but to shift one’s focus to “What now?”.

- Instead of something that can be found passively, meaning is something we actively create.

- Confronting our hardships is key to cultivating resilience, authentic happiness, faith, humility, and compassion.

- The path to meaning is filled with various obstacles – including mental traps like attachment, flawed worldviews (e.g. an excessive emphasis on materialism), and emotional barriers such as the tendency to run away from uncomfortable experiences.

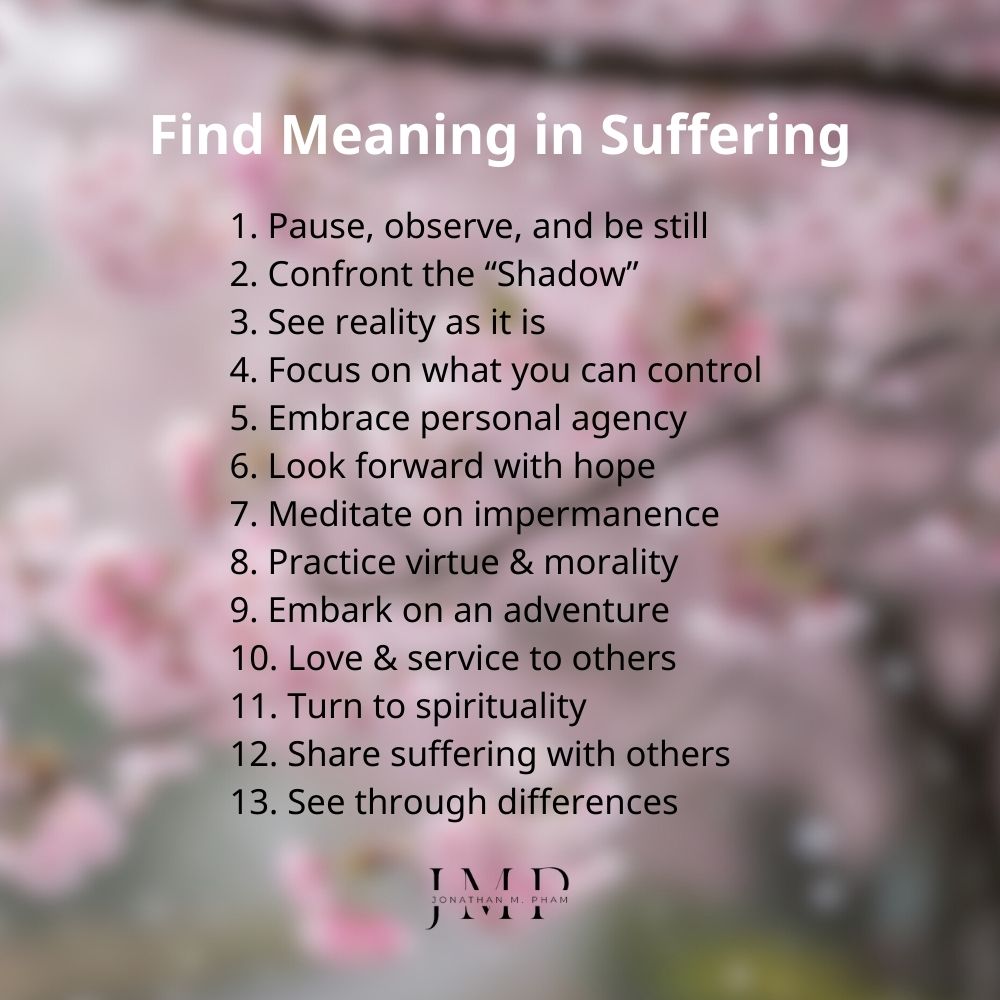

- The process of finding meaning in suffering requires us to accept reality without resistance, actively reframe our perspective, practice virtues, be committed to acts of service, and maintain a deep connection to others.

- Helping those who are suffering starts with a patient, non-judgmental presence; it is the art of deep listening and reminding them of their own inner strength and capacity for joy.

What Does Suffering Mean?

What is this thing we call “suffering”?

If you do a quick search on Google and other search engines, I suppose you should be presented with a lot of technical definitions. Here is the one on Wikipedia:

Suffering, or pain in a broad sense, may be an experience of unpleasantness or aversion, possibly associated with the perception of harm or threat of harm in an individual.

It’s true that physical pain (e.g. injury, illness, etc.) is indeed a real form of suffering. However, our focus here will be more on the one we carry inside us – which, I believe, may be classified into two main forms:

- Mental & emotional suffering

Think about the grief after a loss, the constant anxiety about the future, or the feeling of loneliness in a crowded room.

- Existential & spiritual suffering

This is the pain that arises not from a specific event, but from a perceived lack of meaning. It’s the feeling of being lost – as if one is just going through the motions, and as if nothing really matters. And it is much more common than many of us may think.

About a third of my cases are suffering from no clinically definable neurosis, but from the senselessness and emptiness of their lives.

Carl Jung

The Universal Nature of Suffering

Throughout human history, suffering has always been a constant. Wars and conflicts tear families apart, natural disasters such as earthquakes/ typhoons reshape lives in an instant, and acts of senseless violence leave humanity grappling with shock and sorrow.

It seems that no matter the era, the human condition is always marked by a vulnerability to pain.

These days, humanity has achieved unprecedented levels of convenience and technological marvels. We now have access to more information, more comfort, and more efficiency than any generation before us. And yet, has suffering been removed?

Far from it, I might say. In many ways, it has simply changed its form.

The spiritual void Jung spoke of seems to have widened. In the chase for money and success, many of us end up overworked and disconnected, like robots in a system.

As life becomes more convenient, so too does our appetite for more, leading to a chronic state of dissatisfaction.

Even the rise of AI, a tool designed to free up our time, leaves us busier and more anxious than ever. As AI slowly replaces human work, many find themselves plagued with a wave of existential questions. For example, if a machine can do my job, what is my value?

We become so tethered to our computers and phones, endlessly and aimlessly scrolling through social media, that we forget how to be present with ourselves and with each other.

We become more connected digitally, yet more isolated emotionally.

No matter how much we advance on the outside, the inner landscape of suffering remains. It is universal, and it is here.

Where Does Our Suffering Come From?

This is a question that has been pondered by philosophers, theologians, and thinkers for millennia. Throughout history, various explanations have been offered.

- From a Buddhist perspective, the root of suffering, or dukkha, is not found in the world but within our own minds. It arises from craving, attachment, and a misunderstanding of the transient nature of things. In simple terms, we suffer because we are so desperate to cling to people, experiences, and things that are, by their nature, impermanent.

- The Abrahamic traditions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) tend to view suffering as a consequence of a broken world, a test of one’s faith, or the result of humanity’s free will – which allows us to choose actions that cause pain to ourselves and others. To sum it up, the issue’s root cause has to do with an interplay between a flawed external reality and one’s internal moral choices.

- The Cynics believed that much of human suffering was a product of conventions – societal norms, expectations, and artificial desires. Philosophers like Diogenes advocated that one should reject these things and live “in accordance with nature”. Voluntarily experiencing pain (e.g. living without shelter, begging, wearing simple clothes, going barefoot in all seasons, or enduring insults) was recommended by the Cynics to toughen oneself against external circumstances.

- The Stoics, much like the Buddhists, argued that humanity’s suffering comes not from external events themselves, but from our judgments about them. It is the attachment to things outside of one’s control that causes them turmoil.

- The Existentialists (religious or not) proposed that a certain baseline of suffering is an intrinsic part of the human condition – one that comes from being a self-aware being in a vast, indifferent universe.

- etc.

Finding meaning in suffering

At first glance, these perspectives may seem different; and yet, if we look closely enough, we should realize that they all point toward two main sources of pain:

- What comes from “out there”: The external factors, the events and circumstances we don’t choose and often can’t control (e.g. a sudden illness, the loss of a loved one, a global crisis, etc.). These are subject to fate, chance, and the actions of others.

- What comes from “in here”: Our perceptions, reactions, attachments, and choices – in other words, the way we interpret events and what we decide to do about them.

From my own experience, I believe suffering is rarely a product of just one or the other. Rather, it is the result of an inseparable intertwining of fate and free will.

I don’t know if we each have a destiny, or if we’re all just floating around accidental-like on a breeze, but I, I think maybe it’s both. Maybe both is happening at the same time.

Forrest Gump

From ‘Why’ to ‘What Now’: Key to Finding Meaning in Suffering

When suffering strikes, our first (and completely humane) impulse is to ask: “Why?”

We search desperately for something that can make sense of our pain. Why do good people get sick while the cruel seem to prosper? Why are innocent lives shattered by war and random injustice?

We look at the world and see what appears to be a chaotic, unfair lottery. Why then?

It’s not simple to come up with a straightforward answer that is universally accepted, given that the world is not only black and white – and given that every event is just a “chain” within a whole web of causes and effects that exceeds a single individual’s knowledge. Or, as philosophers like Kant have put it – what we are able to perceive is only phenomena (things as they appear to us, shaped by our subjective senses & experiences), not noumena (things in themselves, independent of our perception and knowledge).

Even what is widely acknowledged by a community is still subject to interpretation (something that I often refer to as collective awareness). For instance, think about humanity’s understanding of a disease (e.g. cancer), which has been evolving constantly over time. What was once seen as a mysterious curse is now understood through a scientific lens of genetics, cell biology, and environmental factors. That said, even this “truth” is still subject to interpretation and new discoveries – not the final word yet.

Or, think about how a historical event, like a war, is often written and accepted differently across countries. The nations involved in the same conflict may come up with very distinct – even conflicting narratives. Each group’s “truth” is shaped by its collective memories, values, and experiences, none of which fully capture the noumena of the incident itself.

Finding meaning in suffering

Throughout history, humanity has come up with systems of belief to address the question. Some traditions point to the workings of karma – in other words, one’s present pain is a debt from a past life. Others see it as a test from God, a “fire” meant to forge one’s character and strengthen their faith.

In the Gospel of John, there is a story about Jesus and his disciples coming across a man who was born blind. The disciples immediately asked:

“Rabbi, who sinned, this man or his parents, that he was born blind?”

“Neither this man nor his parents sinned, but this happened so that the works of God might be displayed in him.”

John 9:1-3

Indeed, from our limited human perspective, we may never know the real “why”. Every explanation one can come up – whether it is karma, the will of God, or something else – is just a means for one to somehow visualize the whole web of causes and effects.

To demand a neat and tidy reason for the universe’s apparent randomness will, most of the time, only bring us to a frustrating dead end.

To live is to be vulnerable to pain. There is no running away from it.

Try to exclude the possibility of suffering which the order of nature and the existence of free wills involve, and you find that you have excluded life itself.

C. S. Lewis

Finding meaning in suffering

That said, some may wonder: if chasing the “Why” is a dead end, where do we turn?

My answer is: we should turn from the external event to our internal experience. To the power of our own perception.

The truth is, human beings rarely react to events themselves; we only react to our interpretation of those events. For instance, one may think of a sudden downpour either as an inconvenience that ruins their day – or as a welcome surprise that is essential for life to flourish. The meaning we assign to the rain is what shapes our experience.

Our suffering, then, is not just what happens to us, but the story we tell ourselves about what happens. As such, we should move from “Why did this happen to me?” to “What should I do now?”

YOUTH: Look, it hasn’t been my intention to find out what kind of life you have led, but I think I’ve started to understand. Basically, without ever having a major setback or encountering overwhelming irrationality, you have crossed the threshold into a world of nebulous philosophy. That’s why you can just toss off people’s emotional scars like they’re nothing. How exceptionally blessed you’ve been!

PHILOSOPHER: It seems you are having difficulty accepting this. Well, let’s give something else a try. This is a triangular column that we use occasionally in counselling.

YOUTH: Sounds interesting. Please explain.

PHILOSOPHER: This triangular column represents our psyche. From where you are sitting right now, you should be able to see only two of the three sides. What is written on those sides?

YOUTH: One side says ‘That bad person’. The other says ‘Poor me’.

PHILOSOPHER: Most of the people who come for counseling start off talking about one or the other. They tearfully complain about the unhappiness that has befallen them. Or, they speak of their hatred for the other people who torment them and the society that surrounds them.

But this is not the point we should be talking to each other about. No matter how much you seek agreement regarding ‘that bad person’ or complain about ‘poor me’, and whether there is someone who listens to that, even if you derive some temporary comfort, it will not lead to a true solution.

The triangular column has another side that is hidden from you now. What sort of thing do you think is written on it?

YOUTH: Hey, stop messing around and just show it to me!

PHILOSOPHER: All right. Please read out loud what it says there.

(And then the philosopher slowly rotated the triangular column with his thin fingers and revealed the words written on the remaining face – the words that shook the youth’s heart)

YOUTH: …!

PHILOSOPHER: Well, say it out loud.

YOUTH: ‘What should I do from now on?’

PHILOSOPHER: Yes, this is precisely the point we should be talking to each other about: ‘What should I do from now on?’ We do not need ‘that bad person’ or suchlike. Neither is ‘poor me’ necessary.

Ichiro Kishimi, ‘The Courage to be Happy’

Finding meaning in suffering

Some might hear this and think it’s an insensitive, even inhumane, response to pain. “How can you just tell someone to move on?”

And yet, I would argue the opposite – that it is the most humane response possible. Simple, because it demonstrates faith in humanity’s strength.

It acknowledges our pain without allowing it to define us.

It honors one’s capacity to rise above the odds, to choose one’s attitude, to take the broken pieces of their life and create something meaningful.

It treats us not as fragile victims of fate, but as the authors of our own destiny.

What Does It Mean to Find Meaning in the Suffering?

Perhaps one was born into this world to accept suffering; and it is because of suffering itself that one must live, must seek happiness, love, and art, must fully enjoy and endure life to its very end.

Bao Ninh, ‘The Sorrow of War’

As human beings, we are wired for meaning. It is an innate drive to make sense of our experiences, both the joyful and the painful.

When faced with chaos, we instinctively search for a pattern; when faced with a story, we look for a moral.

This drive doesn’t vanish in the face of suffering – rather, it only intensifies. To find “meaning” in this context is to find a sense of order, coherence, and purpose within our existence, even when it hurts.

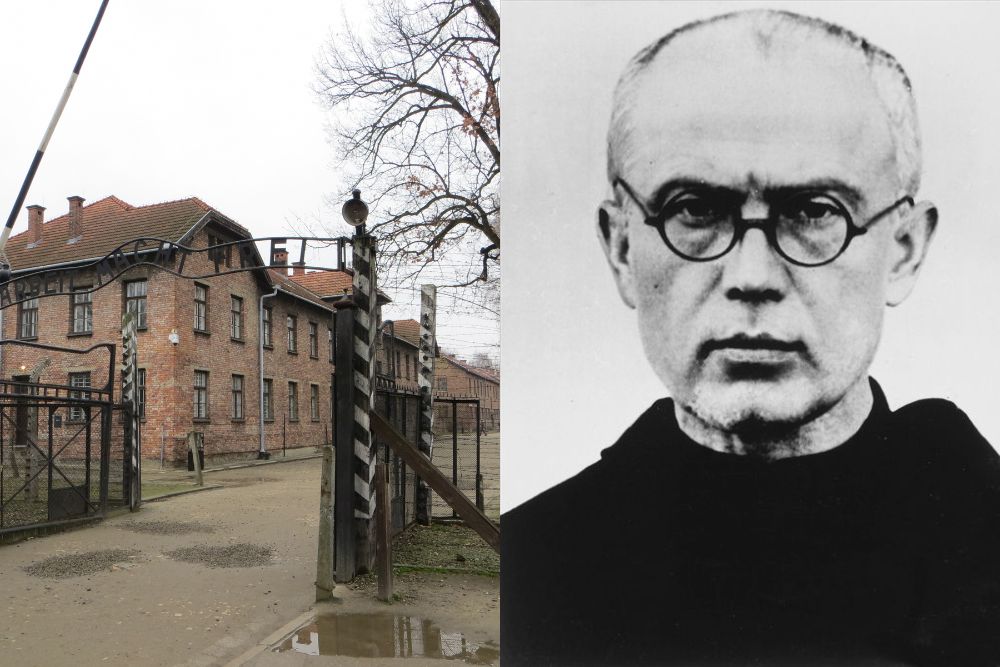

As challenging as it may seem, various figures in history have embodied the essence of finding meaning, even in the darkest of times. One example I find particularly moving is that of Father Maximilian Kolbe, a Polish priest imprisoned at Auschwitz. In 1941, after a prisoner escaped, the guards selected ten men to be starved to death as a punishment. When one of the chosen men cried out in despair (“My wife! My children!”), Father Kolbe stepped forward and offered to take his place. He was then sent to an underground bunker where he spent his final days comforting the other condemned prisoners, leading them in prayer and song.

In a place designed to strip away all humanity, Father Kolbe transformed his own death from a pointless tragedy into a heroic sacrifice – an act of love that affirmed hope and human dignity.

Our saint fellow-prisoner rescued, above all, the humanity in us. He was a spiritual shepherd in the hunger chamber. He strengthened the faith and hope in us who survived the selection. Among this destruction, terror, and the evil, he restored hope.

Michał Micherdziński, recounting the sacrifice of Father Kolbe

Finding meaning in suffering

And then there’s the story of the psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, Viktor Frankl, who was also imprisoned in Auschwitz (among other places). Despite the unimaginable miseries, Frankl was able to keep himself alive by intently holding on to the memories of his wife – and by envisioning a future where he would be free, standing in a lecture hall, teaching students about the psychological lessons he learned in the concentration camps.

There are countless other examples as well, and they all speak to the same truth: humanity is capable of finding meaning in suffering. The moment that happens, we transform suffering from a passive, meaningless affliction into what can be called a “passion”.

On one hand, we accept the reality of the pain; on the other hand, we learn to harness its energy for growth, for understanding, and for action.

In some ways suffering ceases to be suffering at the moment it finds a meaning, such as the meaning of a sacrifice.

Viktor Frankl

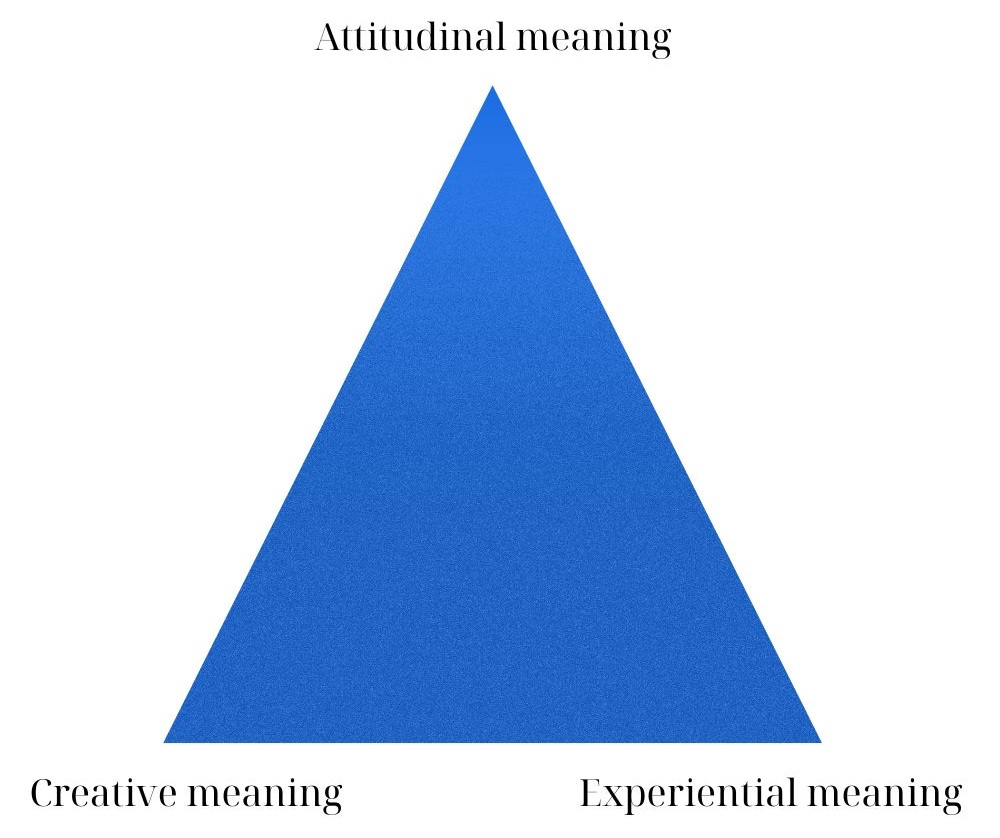

3 types of meaning, proposed by Frankl

What Meaning Can We Find in Our Suffering?

Resilience & strength

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.

Friedrich Nietzsche

I suppose most of you are already familiar with this saying. We’ve heard it so many times that it may feel like some kind of “cliche” (FYI, there is a song with the same name; I happened to know about that song before learning about the quote’s true origin).

As simple as it may seem, the phrase does convey an undeniable truth about the human spirit.

It’s just like going to the gym. When we lift weights, we are creating microscopic tears in our muscle fibers. The pain and stress are necessary for the muscle to heal and rebuild, becoming stronger than it was before. Without that pressure, our bodies would remain weak and undeveloped.

In the same way, suffering serves as a form of “resistance training” for our character. It is through facing and overcoming challenges that we cultivate a deep-seated resilience that can’t be acquired any other way. At the same time, it also presents an opportunity for us to test what we believe in – our values, faith, inner resolve – and find out how authentic they are.

You never know how much you really believe anything until its truth or falsehood becomes a matter of life and death to you. It is easy to say you believe a rope to be strong and sound as long as you are merely using it to cord a box. But suppose you had to hang by that rope over a precipice. Wouldn’t you then first discover how much you really trusted it?

C. S. Lewis

Finding meaning in suffering

Perhaps what’s so incredible about confronting our suffering is that it grants us the ability to shape “reality” – although not in a way that many may expect:

PHILOSOPHER: Once, a man I was counselling recalled an incident from his childhood in which a dog attacked him and bit his leg. Apparently, his mother had often told him, ‘If you see a stray dog, stay completely still. Because if you run, it will chase you.’ There used to be a lot of stray dogs roaming the streets, you see. So, one day he came across a stray dog on the side of the road. A friend who had been walking with him ran away, but he obeyed his mother’s instructions and stayed rooted to the spot. And the stray dog attacked him and bit his leg.

YOUTH: Are you saying that memory was a lie that he fabricated?

PHILOSOPHER: It was not a lie. It is probably true that he was bitten. There had to be a continuation to that episode, however. Through several sessions of counselling, the continuation of the story came back to him. While he was crouching down in pain after getting bitten by the dog, a man who happened to be riding by on a bicycle stopped, helped him get up and took him straight to the hospital.

In the early stage of counselling, his lifestyle, or worldview, had been that ‘the world is a perilous place, and people are my enemies’. To this man, the memory of having been bitten by a dog was an event signifying that this world is a place full of danger.

However, once he had begun, little by little, to be able to think, ‘The world is a safe place, and people are my comrades,’ episodes that supported that way of thinking started coming back to him.

Was one bitten by a dog? Or was one helped by another person? The reason Adlerian psychology is considered a ‘psychology of use’ is this aspect of ‘being able to choose one’s own life’.

The past does NOT decide ‘now’. It is your ‘NOW’ that decides the past.

Ichiro Kishimi, ‘The Courage to Be Happy’

This is the essence of resilience. The miseries that have happened do not determine who one is. On the contrary, it is the meaning one actively creates – the perspective one decides to hold today – that matters.

We can’t erase our scars, but we can reframe our mindset to see them not as evidence of brokenness, but as proof of our strength and ability to persevere.

Life begins on the other side of despair.

Jean-Paul Sartre

Authentic happiness

In our modern culture, happiness is typically imagined as something completely “perfect” – a state free from problems, worries, and pain. Many of us chase this ideal, believing that if we could just eliminate all the negative parts of life, we would finally be happy.

And yet, is it really true at all?

Happiness is not the absence of problems; it’s the ability to deal with them.

Steve Maraboli

Back in the day, many philosophical and psychological frameworks defined suffering as the opposite of pleasure, happiness, or well-being. However, I dare to say that such a view is too simplistic.

Suffering, paradoxically, can be one of the greatest teachers in the art of authentic happiness. It acts like a purifying fire. When we are confronted with the loss of a loved one, a serious illness, or a deep existential crisis, the “flames” burn away everything superficial – the trivial worries that once consumed us, the endless chase for status, the obsession with minor inconveniences, and so on.

Suffering forces us to confront the reality of our own mortality and the impermanence of all things. We stop asking what we can get from life and instead start thinking about what gives life meaning. And suddenly, the answer becomes clear: the time spent with loved ones, the expression of kindness, the pursuit of one’s values – all of these are what make this earthly existence worthy.

At the same time, we learn to become sensitive to and appreciate the daily moments of peace and grace. A quiet morning, a warm cup of tea, a genuine conversation with a friend – these trivial things cease to be ordinary. They become miracles.

Finding meaning in suffering

In the movie “The Seventh Seal” by Ingmar Bergman, there is a scene that captures this perfectly. The story follows a medieval knight returning from the Crusades, journeying through a land ravaged by the Black Death. He is tormented by the seemingly silence of God and the meaninglessness of all the miseries around him. The world, as it appears to him, is one of deep suffering.

Then, one afternoon, he stumbles upon a small family of traveling actors – Jof, Mia, and their young child. These simple, kind-hearted people invite him to share their humble meal: a bowl of wild strawberries and a saucer of milk. As they sit together in the summer sun, the knight’s tormented face softens. For a moment, all his dread and doubt fall away. He says, “I’ll carry this memory between my hands as if it were a bowl filled to the brim with fresh milk, and it will be an adequate sign, it will be enough for me.”

In the midst of a dark and seemingly hopeless world, the knight eventually finds a moment of peace, connection, and goodness. And that, I believe, is a perfect example of what we call “authentic happiness”.

Not a life without suffering – but the ability to find and cherish these small glimmers of light.

The ending of sorrow is the beginning of wisdom.

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Faith

Adult Pi Patel: Faith is a house with many rooms.

Writer: But no room for doubt?

Adult Pi Patel: Oh plenty, on every floor. Doubt is useful, it keeps faith a living thing. After all, you cannot know the strength of your faith until it is tested.

Life of Pi (2012)

Many of us tend to think of suffering as the proof that our beliefs are unfounded. We cry out in pain, and if we are met with silence, we assume it means there is “nothing out there” – that we have been a “blind sheep” all the way.

But what if suffering isn’t the opposite of faith? What if it is the very ground upon which a real, living faith is established?

As discussed above, hardship serves as a “flame” that burns away all things superficial. And I believe that these include our shallow, untested beliefs as well (which I will talk about later).

Have you ever heard about the story of Job? Job is a righteous man who, for no reason he can comprehend, loses everything he holds dear. The apparent absurdity of the universe makes him question himself a lot; and yet, in the end, he chooses to believe and endure – even in the face of utter devastation.

Finding meaning in suffering

While the character is tied to religious texts, I believe we do not necessarily have to interpret his story within the frameworks of a specific religion or a belief in God (which, I assume, can be understood differently across cultures and traditions). In fact, Job’s faith represents something much grander.

It can be a “stubborn” hope in the goodness of humanity, even after witnessing unimaginable cruelty.

It can be a deep-seated belief in a cosmic order, like karma, that we may not fully understand.

It can be an unwavering faith in the power of love and virtue, or a simple trust that, as they say, “life finds a way.”

Whatever its form, such a conviction serves as a reminder that our pain is not pointless, even if its purpose is hidden from us. That our traumas can become opportunities for spiritual growth. That our deepest wounds may turn out to be the greatest sources of strength.

Someone has to start. Other people might not be cooperative, but that is not connected to you. You should start. With no regard to whether others are cooperative or not.

Alfred Adler

Humility & gratitude

The wound is the place where the Light enters you.

Rumi

These days, many of us operate under an illusion of control. We plan our careers, schedule our weeks, and establish identities based on our achievements. We see ourselves as the sole authors of our story, the center of our own “universe”.

Suffering is the force that shatters this illusion. A sudden diagnosis, an unexpected loss, or a crisis that brings us to our knees reminds us that we are not, in fact, in control of everything. That we are but one small part of an interconnected web of life, subject to forces far beyond our command.

If one believes in karma, suffering teaches them that they are not as perfect as they might have thought – bad things happen to them as a result of previous bad karma/ wrongdoings; hence, they should never be so full of themselves, and should instead focus on accumulating good deeds right now.

If one believes in an omnipotent force like God, it gives them the chance to appreciate the value of prayer, respect and love in its unconditional form. To take the first step by themselves and believe completely – even when there are not sufficient grounds for believing.

Finding meaning in suffering

All in all, it is in moments of vulnerability that the walls we put up to protect ourselves – i.e. pride, certainty, ego – may be “broken” open, so that something new may come in.

Once we stop demanding that things conform to our will, we may begin to see life as the gift it is – filled with numerous “miracles” we once took for granted.

When we have faced the possibility of losing everything, that is when we become aware of the sheer wonder of having anything at all: our own breath, the warmth of the sun on our skin, the taste of clean water, the presence of another human being who cares for us.

Life owes us nothing; it has already given us everything. How foolish we have been not to realize its blessings!

High calls low and low calls high. I tell you, if you were in such dire straits as I was, you too would elevate your thoughts. The lower you are, the higher your mind will want to soar.

Yann Martel, ‘Life of Pi’

Compassion

When we are consumed by hardships, it’s natural for the whole world to “shrink” and become confined within our own self. And yet, once we learn to accept reality with courage, that is when our eyes become “opened” – opened to the miseries of others.

After all, suffering is a universal part of the human experience. That said, it is not easy for one to truly understand the struggles of those around them – unless they have been through by themselves.

Once we have walked through our own “fire”, the suffering of another person ceases to be an abstract problem; it becomes a shared reality. We no longer just feel sorry for them; we truly feel with them. And that is the birthplace of true understanding.

We see this in the real world all the time, don’t we? Think about how it’s just natural for doctors who have battled a serious medical condition or lost a loved one to illness to possess a degree of empathy that can’t be acquired from a textbook alone.

It’s also common for those who have been through trauma to become more altruistic, dedicating themselves to helping others navigate similar struggles. Survivors of illness become mentors for the newly diagnosed; parents who have lost a child to a drunk driver create organizations to prevent future tragedies.

In a way, their suffering, which begins as an isolating experience, has turned into a source of healing – one that connects people together.

Finding meaning in suffering

And that’s not all. Have you ever had any conflict with your spouse? For those who are unmarried (like me), I suppose many of you have already witnessed your parents arguing with each other before, right?

It’s not a comfortable experience. And yet, without it, would one have become better aware of their own shortcomings – as well as those of their other “half”? Would one have learned what it takes to humble oneself, appreciate others, and coexist with them?

Now, I’m not saying that I am an advocate for familial conflicts. What I would like to stress is that as soon as you view suffering from a different perspective, you should be able to see that it has never been for nothing. That thanks to it, people may learn the lesson of com-passion – to suffer alongside each other – in a very vivid and memorable manner.

A catalyst for action

Suffering is a sign that you’re out of touch with the truth. Suffering is given to you that you might open your eyes to the truth, that you might understand that there’s falsehood somewhere, just as physical pain is given to you so you will understand that there is disease or illness somewhere.

Anthony de Mello

What if our greatest suffering isn’t a punishment, but a signal? A kind of spiritual “alarm bell”, ringing to tell us that the way we are living is no longer sustainable? That our priorities/ values/ way of being is out of alignment with our “true self” – hence, we need to “wake up” immediately?

One thing in today’s fast-paced world that I find really unfortunate is the fact that many people just “exist” without truly living. We get caught in the rhythm of the daily grind – working jobs that pay the bills but don’t feed our souls, chasing goals that society has set for us without ever questioning their validity.

We scroll and consume, living in a state of comfortable “numbness” just to be “like others”.

We become so accustomed to this passive existence that we don’t even realize we’re, in reality, “asleep”.

Quite often, it takes a life-altering incident – a great loss, a painful failure, or a confrontation with our own mortality – to jolt us awake. Only then may we look back and realize how much of our precious time has been spent on autopilot.

Finding meaning in suffering

Perhaps one of the most moving portrayals of this problem is in Akira Kurosawa’s movie “Ikiru” (meaning: To Live). The film tells the story of Kanji Watanabe, a low-level bureaucrat who has spent thirty years in a monotonous job, shuffling papers and accomplishing nothing. He is, as another character tells him, a kind of “mummy” – already dead, just not yet buried.

Then comes a turning point when Watanabe is diagnosed with terminal stomach cancer and told that he has less than a year to live. The impending death forces him to confront reality. After a period of despair, he remembers a group of women from a poor neighborhood who have been trying, fruitlessly, to get the city to turn a fetid swamp into a children’s playground.

Suddenly, Watanabe finds his purpose. He dedicates his final months to a selfless goal: to cut through the bureaucratic red tape and build that playground. He pours all his remaining life force into this one act of service.

At the climax of the story, viewers are presented with one of the most beautiful scenes in cinema history (my opinion, though). Watanabe sits on a swing in the park he built, in the falling snow, singing a song. He is dying, but he is at peace, filled with quiet joy. His suffering did not destroy him; it saved him. It gave his life a sense of urgency and clarity he had never known before. Thanks to it, he has finally been able to truly live.

Finding meaning in suffering

This is the ultimate gift of adversity. Rather than marking an “end”, it can turn out to be our true “beginning” – a reminder to strive for a more authentic, connected, and purposeful existence.

A man who does not understand the benefit of suffering does not live a clever and true life.

Leo Tolstoy

Read more: 20 Best Existential Movies for the Questioning Heart

Challenges of Finding Meaning in Suffering

Internal traps

Finding meaning in suffering is not easy. Quite often, the most formidable barriers are not in the world around us, but within our own minds.

Attachments & expectations

Constant endeavor to be something, to become something, is the real cause of the destructiveness and the aging of the mind.

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Perhaps the root of all struggles is the tendency to attach one’s happiness to fleeting outcomes. We tell ourselves, “I’ll be happy when I get that promotion,” “…when I buy that house,” “…when I find the perfect partner.” We peg our inner peace to an external, conditional future.

The problem with this thinking is a psychological phenomenon known as the “hedonic treadmill.” We desire something, we strive for it, and when we finally get it, we experience a brief rush of happiness. But then, inevitably, we adapt. The novelty wears off, that new level of success or comfort becomes our new baseline, and we return to our original level of happiness.

Before we know it, we are already looking for the next thing, the next “fix” that we believe will finally bring us lasting satisfaction. It’s a psychological dead end that only guarantees a state of constant craving.

We suffer when we don’t get what we want, and we suffer when we do get what we want – because it’s never enough.

If you don’t get what you want, you suffer; if you get what you don’t want, you suffer; even when you get exactly what you want, you still suffer because you can’t hold on to it forever.

Socrates

The black-or-white outlook

The mind’s tendency is to seek the path of least resistance, and that is why many people simplify our complex world into rigid, binary categories: good versus evil, right versus wrong, us versus them. Such black-or-white thinking provides a sense of certainty (which we all innately crave), but it comes at a great cost. Specifically, it fuels judgment, division, and an inability to see the humanity in those we deem as “enemies,” leading to an unrealistic desire for “justice”.

It is a challenging truth to admit, but the thing is: life is never a clean story with pure heroes and villains; it is a reality where beauty and horror often coexist.

Just think about this. A fridge or an air conditioner always has two sides – one cold, one hot. Essentially, it’s still one single fridge/ air conditioner, but it needs two sides to complement each other.

The same rule applies to society, too. Think of the constant tension between political progressives who push for change and conservatives who seek to preserve tradition. A healthy society needs both to survive and thrive.

Or, consider the relationship between the capitalists who value innovation and the socialists who desire a collective safety net, where nobody is left behind. One pushes us forward, the other holds us together.

And yet, far too often, we tend to look at events in only one way – either too positively or too negatively – without taking a balanced approach. A Middle Path.

In doing so, we have made the choice of cutting ourselves away from others.

What remained was sorrow, the immense sorrow, the sorrow of having survived. The sorrow of war.

But for Hoa and countless other loved comrades, nameless ordinary soldiers, those who sacrificed for others and for their Vietnam, raising the name of Vietnam high and proud, creating a spiritual beauty in the horrors of conflict, the war would have been another brutal, sadistic exercise.

Kien himself would have been dead long ago if it had not been for the sacrifice of others; he might even have killed himself to escape the psychological burden of killing others. He had not done that, choosing instead to live the life of an antlike soldier, carrying the burden of every underling.

After 1975, all that had quieted. The wind of war had stopped. The branches of conflict had stopped rustling. As we had won, Kien thought, then that meant justice had won; that had been some consolation. Or had it?

Think carefully; look at your own existence. Look carefully now at the peace we have, painful, bitter, and sad. And look at who won the war.

To win, martyrs had sacrificed their lives in order that others might survive. Not a new phenomenon, true. But for those still living to know that the kindest, most worthy people have all fallen away, or even been tortured, humiliated before being killed, or buried and wiped away by the machinery of war, then this beautiful landscape of calm and peace is an appalling paradox.

“Justice” may have won, but cruelty, death, and inhuman violence have also won.

[…]

Peace is nothing more than a tree that thrives on the blood and bones of fallen comrades.

Bao Ninh, ‘The Sorrow of War’

Finding meaning in suffering

Speaking of which, I remember once coming across a parable on this theme – albeit from a source that few would expect: the Japanese anime Doraemon. In an episode titled “The Dictator Switch,” the protagonist Nobita is given a button that can make anyone who annoys him disappear – literally. He uses it on his bullies, classmates, and eventually everyone, until he is the only person left on Earth.

At first, Nobita enjoys the newfound freedom, but soon enough, a terrifying loneliness sets in. He realizes that a world without others, even the difficult and annoying ones, is utterly meaningless. It then dawns on him: the richness of life is found not in a “perfect” world free of conflict, but in the ups and downs of human connection.

When we rigidly label people and experiences as purely “good” or “bad,” we erase the very thing that makes life meaningful. Our desire for a world without friction can, if we are not careful, lead us down the path of destruction.

Even saints cannot live with saints on this earth without some anguish. There are two things which men can do about the pain of disunion with other men. They can love or they can hate.

Thomas Merton

Overthinking

This is the trap of creating suffering out of thin air. We get stuck in mental loops, endlessly replaying a past mistake or worrying about a future that hasn’t happened. Many times, we imagine terrible things before we really know if they are real or not.

Have you ever been through a situation like this? You send a message, but the recipient does not immediately respond. You then begin to wonder:

“They must be angry!”

“Did I say something wrong?”, or

“This is not a good sign! What’s going on?”

In reality, the other person is just being busy; in other words, there’s no need to worry at all. You are the only one responsible for your own “suffering”!

As ironic as it may seem, this type of self-inflicted pain is extremely prevalent. Many of us suffer from the anxiety of what might happen, and then if it does happen, we suffer again. We essentially pay interest on a debt we never owe.

It’s a habit that drains our energy and keeps us locked in a mental prison, unable to engage with the present moment.

If a problem is fixable, if a situation is such that you can do something about it, then there is no need to worry. If it’s not fixable, then there is no help in worrying. There is no benefit in worrying whatsoever.

Dalai Lama XIV

The trap of comparison

This may be one of the most toxic behaviors of all in the current hyper-connected world. We look at the curated lives of others on social media and measure our own reality against theirs.

On one side, we compare our pain to someone we perceive as “worse off,” which causes us to invalidate our own feelings (“I shouldn’t feel so bad; others have it so much worse”).

On the other side, we look at those who seem to have it easier; hence, we end up succumbing to envy, resentment, and self-pity.

Both of these paths prevent us from finding meaning in suffering. After all, your pain is your pain. It is valid simply because you feel it. It is not a competition.

There’s no hierarchy of pain. Suffering shouldn’t be ranked, because pain is not a contest.

Lori Gottlieb

Flawed worldviews

All too often, the underlying belief systems that shape our “reality” turn out to be one of the greatest sources of suffering.

Materialism

We live in a strange paradox. By many objective measures – purchasing power, access to information, material comfort – life has become better than ever before. Yet, subjectively, rates of depression, anxiety, and a sense of meaninglessness are soaring.

How can this be?

One reason, as it seems, lies in a worldview that insists on filling an internal, spiritual void with external, material things. We are taught to live to work, to accumulate, to achieve. “Success” is frequently prioritized over value. We chase money, status, and possessions, believing they are the primary ingredients for a good life.

Unbeknownst to many of us, it is exactly this pursuit that causes so much suffering:

- Parents demand that their children pursue unrealistic dreams (e.g. being the best student in class; enrolling in top universities or “hot” majors that do not quite match their vocations; winning in national competitions, etc.). In some cases, the expectations are so unreasonable that the kids decide to commit suicide just because of a very trivial reason (e.g. failing an exam).

- Communities value degrees and reputation so much that some people shamelessly resort to methods such as plagiarizing or hiring someone else to write their thesis.

- Society’s constant emphasis on materialism makes employees unable to realize other values that the company brings to them; the only thing they seemingly care about is salary.

- People’s spiritual life deteriorates; in fact, many people (as I notice) do not even understand what “being spiritual” means. Some even go as far as equating traveling from one country to another with spirituality – some kind of “healing”.

- etc.

Speaking of which, I remember once in my Japanese class, the teacher asked us why we decided to study Japanese. One of the students responded: “Because of money, simply!”

I could not help but think how pathetic such a response was. “But if it’s only for money, you can just learn something else; there’s no need to choose Japanese” – that was what came to my mind at that moment.

It’s really unfortunate that such a mindset has become normalized these days. People make jokes on social media about the fact that salary is the only thing important in work; in other words, life has become reduced to merely a non-stop accumulation of wealth.

There is an ancient parable that speaks directly to this problem. A rich man’s land produced an abundant harvest, so much that he didn’t have room to store it. He thought to himself, ‘This is what I’ll do. I will tear down my barns and build bigger ones, and there I will store my surplus grain. And I’ll say to myself, “You have plenty of grain laid up for many years. Take life easy; eat, drink and be merry.’

And yet, his efforts ended up futile.

You fool! This very night your life will be demanded from you. Then who will get what you have prepared for yourself?

Luke 12:20

When we make materialistic accumulation the primary goal, we build bigger and bigger barns for our possessions, but at the same time leave the soul empty.

We suffer because we are looking for a solution “out there” to a hunger that is “in here.”

Read more: Understanding Yourself – Roadmap to a More Authentic YOU

Blaming the external

Recently, I heard of a Vietnamese intern who murdered a Japanese teacher in Imari for only more than 10,000 yen. Following the tragic incident, one thing I noticed is that many Vietnamese social media pages and groups responded to the event in a somewhat insensitive way. Specifically, most posts and comments were only concerned about the bad impression and consequences the murder was gonna cause for the Vietnamese (e.g. difficulty applying for visas in Japan, etc.). A lot of harsh words for the perpetrator, and yet very few condolences (if any) for the victim and her family.

Image credit: Nikkei

As I reflect on it, I cannot help but be troubled by humanity’s tendency to pass the buck and shift responsibility to others.

When things go wrong, our default instinct is to point a finger. We blame our circumstances, our past, our boss, the government, or something like “fate” for our miseries. It’s a defense mechanism that makes us feel momentarily relieved – at a tremendous cost, though.

If the cause of suffering is always “out there,” then so is the solution. We become passive victims, waiting for the world or people to change before we can find peace (which, many times, does not happen at all).

Can we expect the situation to improve then?

And that’s not all. As we focus excessively on the external, we fail to realize that the “size” of our suffering is, essentially, relative.

For instance, think about how awful it feels for a high-performing student (who always gets A+ in every test) to suddenly receive an average score – compared to one who usually scores average grades. In this case, the former’s “suffering” is not because of the grade itself, but a result of their expectations and desires for others’ recognition.

This may sound a little extreme, but after all, much of our suffering (as demonstrated in the example above) is only a product of our imagination. If it’s just something that we imagine, what do we have to fear then?

To draw an analogy: a man’s suffering is similar to the behavior of a gas. If a certain quantity of gas is pumped into an empty chamber, it will fill the chamber completely and evenly, no matter how big the chamber. Thus suffering completely fills the human soul and conscious mind, no matter whether the suffering is great or little. Therefore the “size” of human suffering is absolutely relative.

Viktor Frankl

Ignorance of impermanence

Everything changes. It’s one of the most basic laws of the universe – one that transcends all religious, cultural, and ideological frameworks.

We intellectually know that all things are transient, yet we live our lives as if we could build a permanent fortress against change.

In his foreword to Frankl’s ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’ book, Harold Kushner mentions a thought-provoking story as follows:

There is a scene in Arthur Miller’s play Incident at Vichy in which an upper-middle-class professional man appears before the Nazi authority that has occupied his town and shows his credentials: his university degrees, his letters of reference from prominent citizens, and so on.

The Nazi asks him, “Is that everything you have?” The man nods.

The Nazi throws it all in the wastebasket and tells him: “Good, now you have nothing.”

The man, whose self-esteem had always depended on the respect of others, is emotionally destroyed.

Reflecting on the story, I cannot help but think about how the man’s suffering came from tying his identity to external things that did not last forever. When they were taken away, he felt he had nothing left.

The same ignorance fuels the “I’ll be happy when…” disease we have discussed previously. It’s the belief that we will finally achieve a permanent state of happiness when we get the next job, the next relationship, or the next achievement.

We are always chasing a future that we believe will be stable and secure, but because nothing is forever, that future never arrives. And in the process, we miss the chance to live fully in the only moment we truly have: the present.

Emotional barriers

These are deep-seated emotional responses that prevent us from finding meaning in suffering.

Avoidance & escapism

The experience of pain is uncomfortable; no wonder most of us would like to run away from it and resort to some avenues of escapism (which are prevalent in today’s world). We lose ourselves for hours in binge-watching a TV series, scrolling through social media, overworking, or using food and drink to dull the ache inside.

It’s true that numbing the pain for a while might feel like a relief; however, it only makes it worse when we finally have to feel it.

It’s like holding a beach ball underwater: it takes constant energy, and eventually, it will burst to the surface with even greater force.

A particularly subtle form of this tendency is known as “spiritual bypassing” – using spiritual ideas to sidestep messy human emotions. It may look like forcing “positive vibes only,” prematurely forgiving someone without ever acknowledging one’s anger, hiding behind a mask of detached tranquility to avoid feeling grief, or (in the case of an individual I know personally) constantly reminding oneself that “the afterlife will be better than this life”.

If we look at it closely enough, we should realize that those behaviors are, after all, results of attachment – one that hinders wisdom and will eventually breed only more anxiety. The more we try to insulate ourselves from our problems, the more fragile we become.

The more you try to avoid suffering, the more you suffer, because smaller and more insignificant things begin to torture you, in proportion to your fear of being hurt. The one who does most to avoid suffering is, in the end, the one who suffers most.

Thomas Merton

Social indifference

In the dawn of morning, there lay the poor little one, with pale cheeks and smiling mouth, leaning against the wall. She had been frozen to death on the last evening of the year; and the New Year’s sun rose and shone upon a little corpse. The child still sat, in the stiffness of death, holding the matches in her hand, one bundle of which was burnt. “She tried to warm herself,” said some. No one imagined what beautiful things she had seen, nor into what glory she had entered with her grandmother, on New Year’s day.

Hans Christian Andersen, ‘The Little Match Girl’

Image credit: NYTimes

Just as we can shut down our own pain, we can also shut down our hearts to the miseries of the world. When the suffering of humanity feels too vast, too constant – broadcast 24/7 on news channels and social media – a part of us is likely to grow numb, simply to survive the overwhelm.

This “compassion fatigue” is a defense mechanism, but it also isolates us. We become “islands”, cut off from our shared humanity. Until one day, we act no differently than the people depicted in stories like Ghibli Studio’s ‘Grave of the Fireflies‘ – rushing past the boys who are dying because of starvation, obliviously.

…

So tragic, right? And yet, I believe there is still hope, if only we start to look inward and work on ourselves today.

How to Find Meaning in Suffering

Acknowledge & accept

Pause, observe, and be still

When we are in pain, our first instinct is to thrash about. We want to do something – anything – to fix the problem, analyze its causes, or numb the feeling. We believe that through frantic effort, we may find a solution.

And yet, have we ever stopped for a second to ask ourselves: how can one find a clear answer with a confused mind?

How can one know the causes of their miseries while in a state of inner turbulence?

As counterintuitive as it may seem, the first step – in many cases – is simply to do nothing at all. Stop resisting, stop fixing, and stop running. Be still.

This doesn’t mean you have to embark on a formal meditation retreat at a church/ temple/ pilgrim site (though that is certainly not a bad idea at all); in fact, it can be as simple as finding a quiet corner in your home, sitting in nature, playing a musical instrument, or just taking some time to focus on your breath.

We should not force the pain away or aim to achieve some kind of blissful state. Just allow the waters of the mind to settle. No need for any formal “techniques” at all.

It is in complete quietness that clarity may truly emerge.

How can I find a true answer when I am confused? If I am confused, I can only receive an answer which is also confused. If my mind is confused, if my mind is disturbed, if my mind is not beautiful, quiet, whatever answer I receive will be through this screen of confusion, anxiety, and fear; therefore, the answer will be perverted.

So, what is important is not to ask, “What is the purpose of life, of existence?” but to clear the confusion that is within you. It is like a blind man who asks, “What is light?” If I tell him what light is, he will listen according to his blindness, according to his darkness; but suppose he is able to see, then, he will never ask the question “What is light?”. It is there.

Similarly, if you can clarify the confusion within yourself, then you will find what the purpose of life is; you will not have to ask, you will not have to look for it; all that you have to do is to be free from those causes which bring about confusion.

Jiddu Krishnamurti

Confront the “Shadow” without fear

Once we become still, we will inevitably meet the very things we have been running from: fear, anger, grief, jealousy. These are the parts of ourselves we tend to label as “negative” or “bad” – our inner “Shadow”. While it’s completely natural for us to want to push them away and make them disappear completely, resistance is a battle we can never win.

There’s a parable that goes like this:

Once there was a young warrior. Her teacher told her that she had to do battle with fear. She didn’t want to do that. It seemed too aggressive; it was scary; it seemed unfriendly. But the teacher said she had to do it and gave her the instructions for the battle.

The day arrived. The student warrior stood on one side, and fear stood on the other. The warrior was feeling very small, and fear was looking big and wrathful. They both had their weapons.

The young warrior roused herself and went toward fear, prostrated three times, and asked, “May I have permission to go into battle with you?”

Fear said, “Thank you for showing me so much respect that you ask permission.”

Then the young warrior said, “How can I defeat you?”

Fear replied, “My weapons are that I talk fast, and I get very close to your face. Then you get completely unnerved, and you do whatever I say. If you don’t do what I tell you, I have no power. You can listen to me, and you can have respect for me. You can even be convinced by me. But if you don’t do what I say, I have no power.”

Finding meaning in suffering

Indeed, our “shadow” emotions will never conquer us – unless we obey them. Instead of “fighting” or resisting them, we simply need to learn to recognize them without letting them control our actions.

“Ah, I see you, anger. You are here.”

As difficult to believe as it may seem, it is in this simple act of non-judgmental recognition that the grip of emotions begins to loosen.

In Japanese art, there is a practice called Kintsugi, where broken pottery is repaired with lacquer dusted with powdered gold. The belief is that the object is more beautiful for having been broken. The cracks are not flaws to be hidden, but a part of the object’s history that should be cherished wholeheartedly.

So too are our own wounds and imperfections. They are not something to be ashamed of, but concrete proof of inner resilience.

Sometimes, while engaging in practices like meditation, prayer, or coaching, one may – from time to time – be hit by a strong wave of emotions. There’s no need to worry or beat up on oneself at all; it’s just a sign that recovery is taking place. And with recovery comes the ability to make peace with oneself and find meaning in everything.

There was no need to be ashamed of tears, for tears bore witness that a man had the greatest of courage, the courage to suffer.

Viktor Frankl

See reality as it is (not as you wish it were)

Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?

Epicurus

I suppose some of you may already be familiar with this statement – which addresses an ancient philosophical question: the problem of evil. Indeed, how could suffering be justified, if a God truly exists?

I wouldn’t want to venture much into theological debates here. What I would like to do is to revisit Epicurus’ argument – particularly, the part “why call him God”.

It makes me question: do we really know what God is? Or are we just imagining God in a way that we want God to be?

What is this thing called “evil” anyway? The act of terrorism vs the terrorists themselves – which of them is “evil”?

A vast amount of our suffering comes from the gap between how we believe the world should be and how it is. We cling to rigid dogmas and preconceived notions – and when reality shatters them, we suffer.

For instance, many of us hold the belief that a good and all-powerful God should prevent all evil. When tragedy strikes, our ideology is shaken not by the event itself, but by the fact that the event contradicts our rigid expectation of how God should operate.

Whether you are a Christian, a Muslim, a Hindu, a Buddhist, or even an atheist (in that case, I believe you can think of God as the universe, a cosmic order, or something similar), we cannot – as I figure – know for sure about what God is based on ancient scriptures alone. Doing so will only result in a paradox of thought, as you eventually have to confront the absurdity of reality.

What’s important, I believe, is to look at the world, in all its beauty and horror, and not insist that it conform to our will. Only when we demonstrate the courage to do it may we have a faint idea of what God is.

Finding meaning in suffering

My spiritual mentor once posed a very thought-provoking question – that is, how can we use the part to demonstrate the whole?

When we define something, we always have to rely on a greater whole to describe it (e.g. a computer is a device that is…; in this definition, “device” is the whole, “computer” is the part). But when it comes to the Whole itself (God/ the Universe/ The Soul of the World), how can we describe it?

How can we, with our finite minds and limitations in terms of language, be able to comprehend the Infinite?

For my part, I believe that one can never describe the Whole; rather, they just have to experience it themselves.

Think of it like trying to describe the color blue to someone who has been blind since birth. You can use all the words you know – you can talk about wavelengths of light, feelings, and associations – and yet, you can never truly convey the subjective experience of seeing blue. The person must experience it for themselves.

So it is with life’s greatest mysteries. Since we cannot fully comprehend the ultimate ‘Why’, our greatest power lies in how we decide to experience and respond to what is.

Finding meaning in suffering

The world is full of absurdities that no single explanation can satisfy everyone. Instead of holding the universe responsible for life’s unfairness, I believe it’s much more constructive to stop and ask:

“If this has happened to me, what do I do now, and who is there to help me do it?”

While we may not have chosen our circumstances, we are free to choose our actions. It is the foundational ground upon which a meaningful life may be built.

There is no such thing in the world as absolute evil or absolute good. There is good to be found within evil, and plenty of evil to be found within the good.

Shusaku Endo – recounted by Endo’s son, Ryunosuke

Reframe & reclaim agency

Focus on what you can control

A cornerstone of ancient Stoic wisdom is the idea that some things are within our power, and some are not. Our suffering is amplified when we waste energy trying to control what we can’t – the past, other people, external events – while neglecting the one domain where we have true authority: our own mind.

To better demonstrate the point, let us reflect on the following story, shall we?

There was once a king who offered a prize to the artist who could paint the best picture of peace. Many artists tried. The king looked at all the pictures. After much deliberation he was down to the last two. He had to choose between them.

One picture was of a calm lake. The lake was a perfect mirror for the peaceful mountains that towered around it. Overhead fluffy white clouds floated in a blue sky. Everyone who saw this picture said that it was the perfect picture of peace.

The second picture had mountains too. These mountains were rugged and bare. Above was an angry sky from which rain fell. Lightning flashed. Down the side of the mountain tumbled a foaming waterfall. This did not appear to be a peaceful place at all.

But, when the king looked closely, he saw that behind the waterfall was a tiny bush growing in the rock. Inside the bush, a mother bird had built her nest. There in the midst of the rush of angry water, sat the mother bird on her nest. The king chose this picture as the perfect picture of peace.

The king chose it, “Because,” he explained, “peace is not only in a place where there is no noise, trouble or hard work. Peace is in the midst of things as they are, when there is calm in your heart. That is the real meaning of peace.”

Finding meaning in suffering

We cannot always calm the storm outside, but we can always find the calm within our own hearts. It is the ultimate power that we, as human beings, possess.

Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.

Viktor Frankl

Embrace the power of choice & personal agency

In an interview following the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks, the Dalai Lama offered an insightful perspective as follows:

People want to lead a peaceful life. The terrorists are short-sighted, and this is one of the causes of rampant suicide bombings. We cannot solve this problem only through prayers.

I am a Buddhist and I believe in praying. But humans have created this problem, and now we are asking God to solve it. It is illogical.

God would say, solve it yourself because you created it in the first place.

Far too often, we relinquish our ability to control things and instead blame others for our miseries. It’s true that many of the world’s tragedies are caused by those “out there” – but, as we have discussed, it does no good to just stay inactive and “pray” for things to change, without doing anything.

While we are not always to blame for the cards we are dealt, we are entirely responsible for how we play them. It means rejecting determinism – the idea that our genetics, upbringing, or circumstances define who we are.

Practicing personal agency is a skill one may cultivate – a way of strengthening one’s character. It is the conscious decision, in every moment, to respond with integrity rather than resentment, with courage rather than fear, with compassion rather than hatred.

This is the ultimate “weapon” one has to persevere and triumph against the most extreme circumstances.

In the concentration camps, for example, in this living laboratory and on this testing ground, we watched and witnessed some of our comrades behave like swine while others behaved like saints. Man has both potentialities within himself; which one is actualized depends on decisions but not on conditions.

Viktor E. Frankl

Look forward with hope

Just about a century ago, the whole world was engulfed in a terrible conflict – World War I. It was one of the most devastating incidents humanity has ever known – one that leaves behind deep scars in society.

In the aftermath of WWI, the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, witnessing the immense destruction, proposed the existence of a “death drive” (Thanatos) in humanity – which, he believed, helped explain the absurdities of that time. On the other hand, the psychologist Alfred Adler, who served as a medical officer in the war, took a completely different approach. He asked, “How can we prevent this from happening again?” and dedicated his work to developing his theory of “community feeling“.

The same event – and yet two separate routes taken. One focused on the cause of the problem, one on the solution. One looked back at the darkness; the other forward toward the “light”.

In which direction should we look then?

It is tempting to pick the first path – gazing backward at the ruins of what we’ve lost. And yet, doing so will only trap us in an endless cycle of misery. Only by courageously looking forward – despite all the odds – may we be motivated to take action, and find meaning in the process.

Speaking of which, I cannot help but recall the story of the 1914 Christmas Truce. In the midst of the brutal trench warfare, soldiers on both sides spontaneously laid down their arms on Christmas Day. They shared gifts, sang carols, and saw the humanity in their so-called “enemies”.

Finding meaning in suffering

A truly moving story, and yet it is also a popular source of mockery. In fact, I once attended a Christmas party where some participants mentioned and made fun of it:

“They were friendly on Christmas, but then they went back to killing each other after that. So what was the point? It didn’t change anything.”

I assume that’s one way to look at it; however, I also believe that using the Truce solely for mockery misses the human element of the story.

To me, the incident’s significance lies not in its failure to end the conflict, but in how it showed that the human capacity for connection and hope can blossom even in the most dire circumstances.

It’s all about our choices – would we wish for meaning, or would we wish for something else?

Read more: Hiroshima Rages, Nagasaki Prays – A Personal Reflection on Peace & Meaning

Meditate on death & impermanence

Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds.

John 12:24

The practice of meditating on death is one widely advocated by many spiritual and philosophical traditions (the Stoics referred to it as “Memento Mori“). On the surface, it may seem morbid and uncomfortable; however, I strongly believe that it holds the key to overcoming life’s sufferings.

In Daoist philosophy, there’s a story that goes like this:

Zhuang Zi’s wife passed away, so his old friend Hui Zi came for a visit of condolence. When he arrived, he saw that Zhuang Zi was sitting on the ground, drumming a pot and singing a song. He did not seem to be grieving, and this seemed very inappropriate to Hui Zi.

He said to Zhuang Zi: “What are you doing? Your wife has been there for you all those years, raising your children and building your family with you. Now she is gone, but you feel no sadness and shed no tears. You are actually drumming and singing! Isn’t this a bit much?”

“It’s not what it looks like my friend.” Zhuang Zi faced Hui Zi’s emotions. “Of course I was struck with grief when she passed on. How could I not be? But then, I realized that the life I thought she lost was actually not something she had originally. During all that time before her birth, she did not possess life, a physical form, or indeed anything at all. She ended up in exactly the same state, so she did not lose anything.”

Her death was a transformation, just like when she was conceived and born,” Zhuang Zi continued. “In that state between existence and nonexistence, her initial transformation gave rise to energy. That energy gave rise to a physical form, and that physical form took on life to become a human being. Now it’s the other way around, as her continuing transformation returns her to the Dao. This whole process – from nonexistence to life, from life back to nonexistence again – is like the changing of the seasons, all completely in accordance with nature.”

Hui Zi nodded. Somehow, Zhuang Zi’s behavior no longer seemed as inappropriate as before. He said to Zhuang Zi: “Since the transformation is perfectly in accordance with nature, it is not something to be sad about, just like you and I would not cry over autumn changing to winter.”

“Yes. She is now resting peacefully in the hereafter, without all the constraints and limitation of life. The more I think about that, the more silly it seems to cry my eyes out. I will always miss her, but it is not necessary for me to grieve for her as if her death were a great tragedy.”

Finding meaning in suffering

If a loved one passes away, for sure we will be sad – but not for long. For some of you, isn’t it that years ago, both of your grandparents were still alive – and now one (or both) of them are already gone?

For some of you, isn’t it that your hair has started to turn grey already?

Almost a thousand years ago, the Mongol empire was a force to be reckoned with – something that struck fear into people’s hearts. Their land spanned from East Asia to Europe – more than half of the Old World back in the day.

A hundred years ago, the whole world was engulfed in two terrible global conflicts (WWI & WWII) that threatened to wipe out humanity.

Fifty years ago, Singapore was still a poor fishing village that virtually nobody knew about.

Twenty years ago, the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami caused unbelievably widespread destruction – something that humanity had not experienced for a while.

Just about 15 years ago, another similar event occurred: the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami – followed by the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

5 years ago, the whole world was torn apart by the Covid-19 pandemic.

3 years ago, AI tools like ChatGPT were not yet a thing at all. Look at how things have changed since then!

Now humanity is again in turmoil, and we are still here.

Ten or twenty years from now on, some of us will still be alive – and some will be gone.

After 120 days, every single one of our red blood cells has been replaced. After 120 years, every person who walked the Earth has passed on.

…

All things are impermanent. When we understand the world’s transient nature, we are no longer inclined to cling to anything. And we also realize, that it is truly a grace to be born – born as a human being, capable of thinking, observing, learning, attaining wisdom, adhering to ethical standards, and preparing for what is about to come after this earthly existence.

With that insight comes the motivation to focus on what truly matters – to find joy and purpose in the here and now, rather than succumbing to life’s miseries, being obsessed with “I’ll be happy when…”, or wasting time arguing about ideologies with each other.

Because one day, all will pass.

One day, we will have to let go of all finite “forms”, and open ourselves to something formless and boundless.

When you practice looking deeply, you see your true nature of no birth, no death; no being, no non-being; no coming, no going; no same, no different. When you see this, you are free from fear. You are free from craving and free from jealousy. No fear is the ultimate joy. When you have the insight of no fear, you are free. And like the great beings, you ride serenely on the waves of birth and death.

Thich Nhat Hanh

Finding meaning in suffering

Cultivate & create

Practice virtue & morality

When the world outside is in chaos – when our lives are unstable – we need a reliable inner compass. And that compass is what I call “virtue”.

In the midst of suffering, anchoring oneself in principles like compassion, integrity, love, and honesty provides a sense of stability that no external circumstance can take away.

When we are faced with countless confusing choices, all it takes to navigate through the situation is to stop and ask ourselves one single question:

“As a human being, what is the right thing for me to do?”

This question was what the late Japanese entrepreneur Kazuo Inamori – known for his unique business philosophy “Respect the Divine and love people” (敬天愛人) – used to overcome his life’s troubles and times of uncertainty. It helps us see past the ego, fear, and greed, guiding us to do what’s genuinely right.

Image credit: Kyocera Europe

Virtue is the force that allows us to make sense of our pain (despite the absurdities) and resist the temptation to respond with bitterness or cruelty.

It is what enables us to stop spreading suffering to others – whether by complaining, badmouthing, harming people, or resorting to self-destructive behaviors (e.g. withdrawing from social life, drinking, nighttime entertainment, online gossiping, suicide, etc.).

Even in the face of seemingly unfair miseries (e.g. a mass shooting incident), with virtue, one should be able to refrain from impulsive acts – e.g. venting one’s anger onto those deemed as the cause of their suffering, whether with bullets, harsh words, or satires.

Does it mean one should remain idle and take no action against injustice? Quite the opposite, I dare to say.

We should speak out the truth – but with a little perspective and compassion, knowing that what one does always impacts others, and knowing that the “truth” is always subjective and therefore should not be subject to generalization.

Hatred is not appeased by hatred in this world. By non-hatred alone is hatred appeased.

Dhammapada

Embark on an “adventure”

We are permitted doubt. But we must move on. To choose doubt as a philosophy of life is akin to choosing immobility as a means of transportation.

Yann Martel, ‘Life of Pi’

Once suffering has shaken us from our slumber, we are called to move forward. This means consciously choosing to embark on a new “adventure” – not necessarily a trip to a faraway land, but the pursuit of a purpose or a cause that is larger than our own pain.