Why am I me and not somebody else?

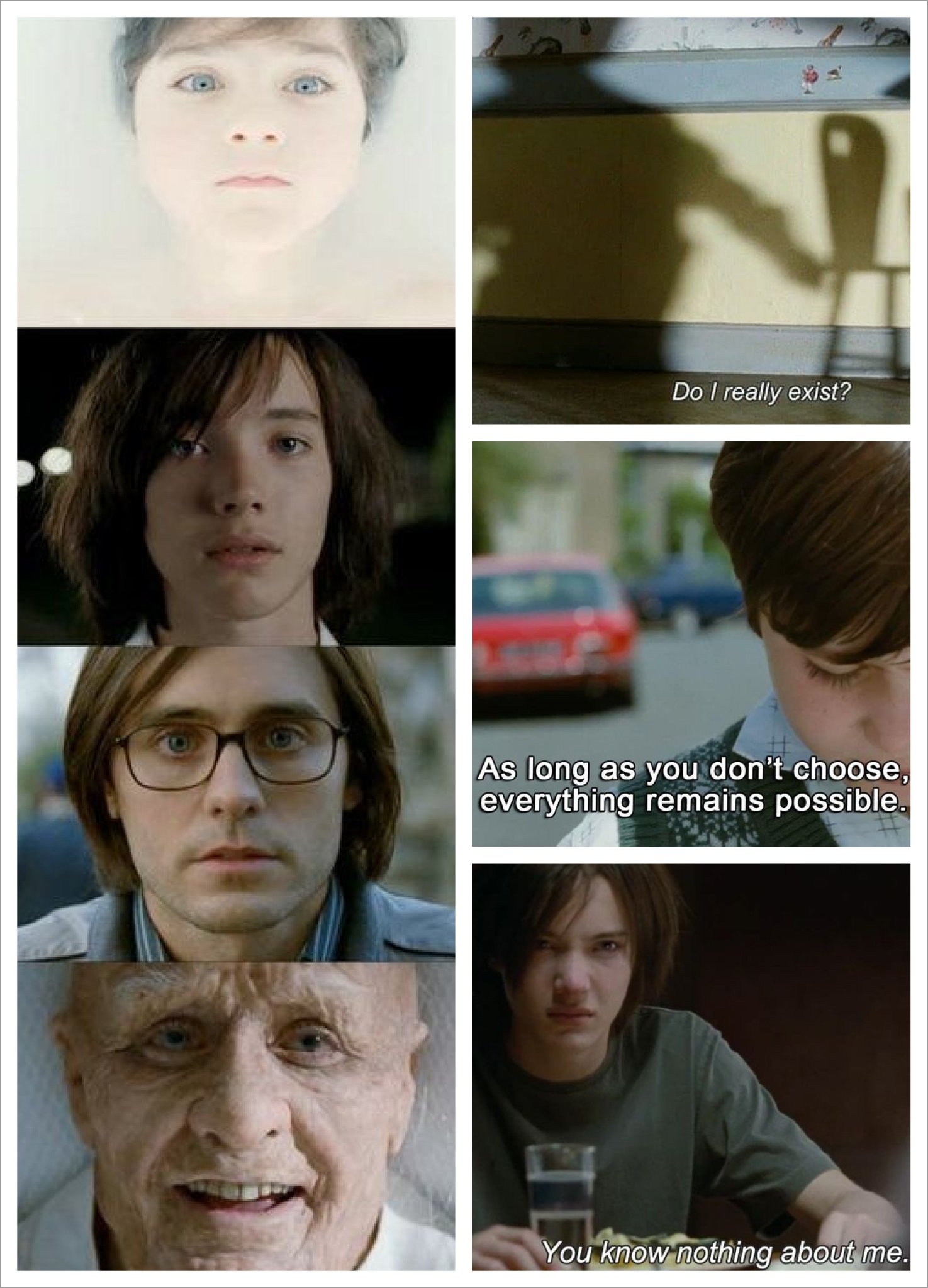

Nemo, ‘Mr. Nobody’ (2009)

Have you ever asked yourself this question before?

I certainly have. It takes me back to being a kid, a time long before I consciously started my self-discovery journey, before I knew words like ‘existentialism’ or had what I’d call ‘philosophical thoughts’. Back then, it was pure wonder:

“Why am I seeing the world through these eyes? Why am I in this body instead of someone else’s body? Why am I not another person?”

“Why am I a boy, not a girl?”

“Why do I exist? Why am I?”

“How would I ‘feel’ when all of my senses are gone (i.e., I die)?”

“Who am I?”

Maybe those sound like silly questions now, something to dismiss with a ‘Why bother?’

It’s a fair reaction in a world that demands answers and actions, not just pondering. These existential questions don’t pay the bills or finish the chores.

And yet… isn’t there something deeply human about asking them?

Doesn’t wrestling with the sheer improbable fact of your own specific existence – of the incredible, fragile, unique thing we call ‘self’ – feel… important?

After all, the quest for finding one’s identity is a universal human experience – this quiet nudge to understand who we are beneath the surface. And delving into it is, I think, far more than just an abstract philosophical exercise.

In fact, I believe it plays a crucial role in helping us better navigate our lives, both individually and together. This is especially true when one faces moments of difficulty or uncertainty (e.g. during maturity; following an environment change; after a major crisis or setback; during a life/ career transition; following an experience that fundamentally challenges one’s view on life/ values/ the world, etc.). These moments, as I have figured, are something we all experience at some time in our lives.

Now, it’s important to say that when it comes to the ‘self’, people hold vastly differing viewpoints. Throughout history, thinkers, dreamers, and everyday individuals have grappled with the complexities of self-identity from a multitude of angles, some of which are seemingly “incompatible” with each other.

For my part, I do not intend to present a definitive answer – I certainly don’t have one (and I’m not sure if there is one accepted by everybody)! Instead, my hope is to explore some of these fascinating perspectives and questions together.

Think of it as an invitation: not for me to tell you who you are, but to stimulate your own reflection and encourage you on your unique path of discovering that for yourself.

With that spirit of curiosity, let us dive in, shall we?

(Note: You can download the pdf version of the article – also the Q2-2025 edition of my newsletter series by clicking here)

Highlights

- Self-identity is not a simple label; it involves a dynamic and evolving understanding of who we are, shaped by a rich interplay of inner experiences and outer worlds. As such, it is best approached with an appreciation for its inherent complexity.

- A clear and authentic sense of self is foundational to a life imbued with meaning, fostering genuine connections, nurturing inner resilience against life’s challenges, and paving the way for personal transformation.

- Life often presents distinct internal stirrings – such as feelings of misalignment or a yearning for deeper purpose – and significant external transitions that serve as potent invitations to pause and consciously explore one’s self-identity.

- When explored from within, our self-identity reveals its inherent nature as richly multifaceted and deeply personal, constantly evolving through time, fundamentally interconnected with all life, possessing both empowering and limiting potentials, and holding a remarkable capacity for transcendent awareness.

- The path toward self-knowledge involves courageously navigating significant challenges – including internal delusions about the ego, ingrained psychological traps like fear and limiting narratives, pervasive external societal pressures, and various unique complexities introduced by our modern digital age.

- Truly realizing one’s self-identity requires an active inner journey; it calls for the dedicated cultivation of essential qualities such as courage, honesty, humility, self-awareness, and self-compassion.

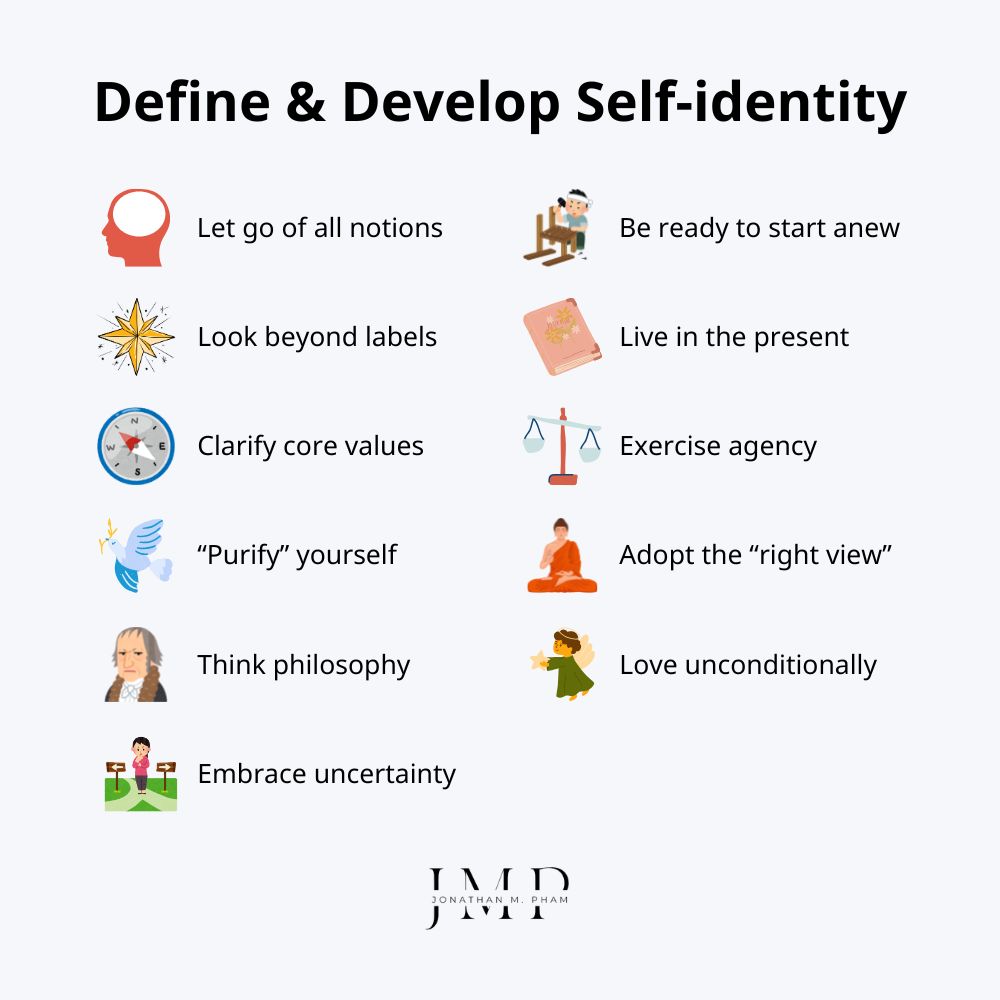

- We actively shape and develop a more authentic self-identity through ongoing, conscious practices like letting go of fixed notions, clarifying our core values with flexibility, embracing present-moment awareness and life’s inherent uncertainty, exercising our personal agency, cultivating a clear and compassionate view of reality, and ultimately, choosing love as our guiding principle.

What is Self-identity?

When the phrase “self-identity” comes up, what springs to your mind?

For many of us, the immediate answers might be our name, our profession, the roles we play like “parent” or “friend,” perhaps our most prominent personality traits – “I’m an introvert,” “I’m ambitious,” or even our cherished hobbies, “I love hiking.”

These are, undoubtedly, parts of how we describe ourselves to the world, and to ourselves.

But do these labels, these surface-level identifiers, truly capture the entirety of who you are?

Is your identity merely a collection of roles, characteristics, and preferences, or is there something more profound, something deeper at its core that these descriptors only hint at?

Definition & related concepts

Let’s start with a preliminary idea: Self-identity is the dynamic and evolving understanding of who we perceive ourselves to be. It’s far more than a static list of qualities; it’s a living process shaped by our innermost experiences, our personal history, the web of our relationships, and the world that surrounds and interacts with us. Think of it as both an internal compass that guides our choices and the unfolding story we continuously author about who we are and are becoming.

The concept of “self-identity” is closely related to, yet distinct from, a few other psychological terms that are helpful to know:

- Self-concept often refers to the more descriptive and evaluative picture we hold of our own abilities, attributes, and characteristics. It’s the “who I think I am” inventory.

- Self-image is a component of this, specifically how we see ourselves, which is under the influence of many factors.

- Self-esteem, then, is the emotional charge on that self-concept – how we feel about who we perceive ourselves to be, the value we place on it.

Sometimes, you may hear people referring to “self-identity” with terms such as “personal identity”, the “sense of self”, or simply the “self”. Strictly speaking from an academic perspective, these terms are not quite the same; however, for the purpose of our exploration here, we will consider them as pointing to the same broad phenomenon and use them somewhat interchangeably to refer to that complex, multifaceted experience of individuality, personal existence, and our ongoing inquiry into “who I am.”

Unpacking “Self” through different windows

To truly appreciate what self-identity might encompass, it’s enriching to peer through various “windows” – different fields of human inquiry that each offer unique tools and insights into this complex phenomenon.

A. The psychological lens: Understanding the ‘mechanics’ of self

Psychology provides us with practical, often empirically grounded, insights into how our sense of self develops, how we experience it, and how it functions in our daily lives. It helps us grasp some of the tangible aspects of who we are. Key concepts typically explored include:

- Identity formation: The journey, especially prominent in adolescence but truly lifelong, of forging a coherent and consistent sense of who we are.

- Self-concept & self-esteem: These act as building blocks, forming the content and evaluation of our self-perception.

- Personality traits: Those relatively enduring patterns in our thinking, feeling, and behaving that contribute to our uniqueness.

- Memory: The crucial thread that weaves together our past experiences, present awareness, and projections of a future self, creating a sense of continuity.

Psychology also illuminates how our self is, in many ways, “intersubjective.” It exists not just in our private consciousness, but also in how we imagine others perceive us, and in the interplay between our “I” (the subjective experiencer) and our “me” (the self as an object of our own and others’ reflection). Our interactions and interpretations of how others see us constantly shape this sense of “me.”

B. The sociological lens: The self in society

Sociology broadens the view, highlighting how profoundly our identity is shaped by the social structures and cultural contexts we inhabit. It reminds us that we are not formed in a vacuum.

Our social roles (as a parent, an employee, a citizen, a friend), our group affiliations (based on culture, nationality, subcultures we belong to, or even shared interests), and the overarching cultural narratives of our society all contribute significantly to defining who we believe ourselves to be and how we fit into the world.

C. The neuroscientific glimpse: The brain and self

A newer, yet rapidly advancing, perspective comes from neuroscience. While the mystery is far from fully solved, neuroscience is beginning to map how the intricate workings of our brain activity contribute to our continuous sense of being a distinct individual, our self-awareness, and even our memories and sense of personal history. It’s a complex and evolving field, offering fascinating glimpses into the biological underpinnings of our subjective experience of self.

Recent research is revealing that self-awareness isn’t tied to a single brain spot but involves widespread brain networks. Crucial areas, like parts of the prefrontal cortex, help weave our memories together to form a consistent sense of who we are over time, and damage here can indeed impact our identity.

Intriguingly, practices like mindfulness have been shown to change brain activity related to how we process and experience our ‘self’ – potentially fostering a healthier and more adaptable self-perception.

D. The philosophical quest: Fundamental questions of being

Philosophy, for millennia, has been the arena for grappling with the most fundamental questions about the nature of the self, existence, and meaning. It invites us into deeper introspection and critical thinking.

Some core philosophical inquiries relevant to self-identity include:

- The nature of the self: What truly constitutes the “I” that thinks, feels, and experiences? Is it a soul, a mind, a process, or something else entirely?

- Personal continuity: What makes you the same person across time, despite all the physical and psychological changes you undergo? This involves age-old questions, sometimes explored through thought experiments, about how we remain recognizably “us” through the constant flow of change.

- Consciousness: What is the role of conscious experience in defining who we are? Is it central to our identity?

- Existentialism: Briefly, this branch of philosophy emphasizes our freedom and responsibility in creating our own meaning and, by extension, our own self, in a world that may not offer inherent purpose.

It’s worth noting here that much of Western philosophical thought, historically, has placed a strong emphasis on the idea of a core self that demonstrates sameness and continuity over time.

Cultural perspectives of the “Self”

As we start to see, defining self-identity isn’t straightforward. The challenge is magnified when we consider the vast diversity of philosophical and cultural viewpoints around the world.

- Western cultures, for instance, have often emphasized concepts of personal independence, individual achievement, and a view of the self as a distinct, autonomous, and continuous entity.

- In contrast, many non-Western cultures (including various Indigenous, Asian, and African traditions) promote a more interdependent view of the self. Accordingly, identity is typically understood through its deep connections to family, community, nature, and social roles. Concepts like the Buddhist notion of anatta (no-self or non-essential self) highlight impermanence rather than enduring sameness, while Confucian thought emphasizes relational identity, where the self is defined and cultivated through its harmonious participation in social relationships.

Given these diverse perspectives, especially the contrasting emphasis on enduring “sameness” versus inherent “impermanence” or “relationality,” crafting a single, universally agreed-upon definition of self-identity is indeed challenging, if not impossible.

Toward a more inclusive view

Perhaps instead of seeking a rigid, definitive answer, let’s think of self-identity as our ongoing engagement with the fundamental questions of who we are. It’s about what it means to be you – how you connect with your past and envision your future, and what makes you distinct from others. This includes:

- Your subjective feeling of being a continuous person, that inner sense of “I-ness” that experiences life.

- Your physical presence, your body as a vehicle of experience in the world.

- Your unique psychological makeup, encompassing your memories, personality patterns, beliefs, and values.

- Your roles and relationships, which connect you to others and to society.

- And crucially, the stories and narratives you weave about your life to make sense of it all.

As you may see, the idea here is to cultivate a more inclusive, “transcendent” view that:

- Focuses on the universal human “concern” or the “questions” about identity, rather than presupposing a single, fixed answer.

- Embraces multiple dimensions – the felt sense, the physical, the psychological, the social, and the narrative – recognizing that identity isn’t just one thing.

- Acknowledges the “felt sense” of continuity as a common human experience, which is a starting point for many discussions, without making it the sole, absolute criterion for identity.

- Avoids locking into one specific metaphysical basis for identity (e.g., it doesn’t insist that identity is only a soul, only the body, or only psychological states).

- Allows for the dynamic and evolving nature of identity, acknowledging that who we are may change and develop later.

Whether one’s personal conviction or cultural background prioritizes an enduring core self, psychological continuity, relational roles, or the impermanence of all things, the questions and experiences related to identity remain profoundly central to the human condition.

And even if we accept that our identity is subject to change, the practical need to recognize individuals over time for social, moral, and legal reasons remains. Most philosophies and societal structures, even those emphasizing impermanence, offer ways to understand this perceived continuity in daily life.

The Importance of Self-identity

So far, we’ve affirmed that there is indeed something profound and deeply significant to this concept of “self” or “individuality” – something that warrants our sustained curiosity, our most honest introspection, and our dedicated reflection. It’s not just an abstract puzzle for thinkers in ivory towers; the nature of who we perceive ourselves to be touches every aspect of our lives.

But why is understanding it so crucial? What real difference does it make to embark on this journey of self-discovery?

Akin to knowing/ remembering one’s “true name”

Have you ever encountered stories where knowing something’s – or someone’s – “true name” grants a special kind of insight or power?

Across countless cultures and throughout history, names have often been considered far more than mere labels. They’re seen to carry deep meaning, reflecting lineage, destiny, perhaps even the very essence of one’s personality.

A “true name,” in this almost mythical sense, is imagined as the very core of a person’s being, their authentic self.

This yearning to grasp one’s fundamental being echoes in ancient scriptures. The Book of Exodus recounts the encounter of the prophet Moses with God on Mount Sinai. As he was about to be sent on a mission to liberate the Israelites, Moses asked God what his name was, to which he received the reply:

As human beings, we all wish to not just have an identity, but to deeply realize and affirm our own unique existence and nature. From this self-knowledge, our sense of place in relation to others and to the world itself begins to clarify.

The concept of a “true name” holding deep significance is a recurring motif in humanity’s collective storytelling, from philosophical dialogues to epic adventures and modern tales.

- In Plato’s Cratylus, Socrates explores whether names are merely conventional sounds or if they can possess a “natural correctness,” somehow reflecting the true essence of the thing named. Simplified for our purposes, this philosophical musing touches on the idea that a “true” understanding, like a “true name,” aligns with the inherent nature of a person or thing.

- In Ursula K. Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea, the magic of the world is intrinsically tied to knowing the true names of things and beings. Learning these names grants power, and the protagonist Ged’s journey is largely about mastering this responsibility, including the perilous path to knowing his own true name.

- Similarly, in Christopher Paolini’s Eragon, the true name of any being holds immense power; discovering one’s own is a pivotal moment of self-understanding and central to a character’s entire development and destiny.

- In Kung Fu Panda 2, the protagonist Po’s plaintive question, “Who am I?” drives his entire arc. While not explicitly about a magical “true name”, Po’s concern was about the truth of his origins and his being, the discovery (and acceptance) of which is key to unlocking his inner power.

- Rey’s journey in the Star Wars saga also echoes this, as she grapples with questions of lineage, belonging, and her place in a galaxy-spanning conflict, seeking to comprehend the forces that shape her identity.

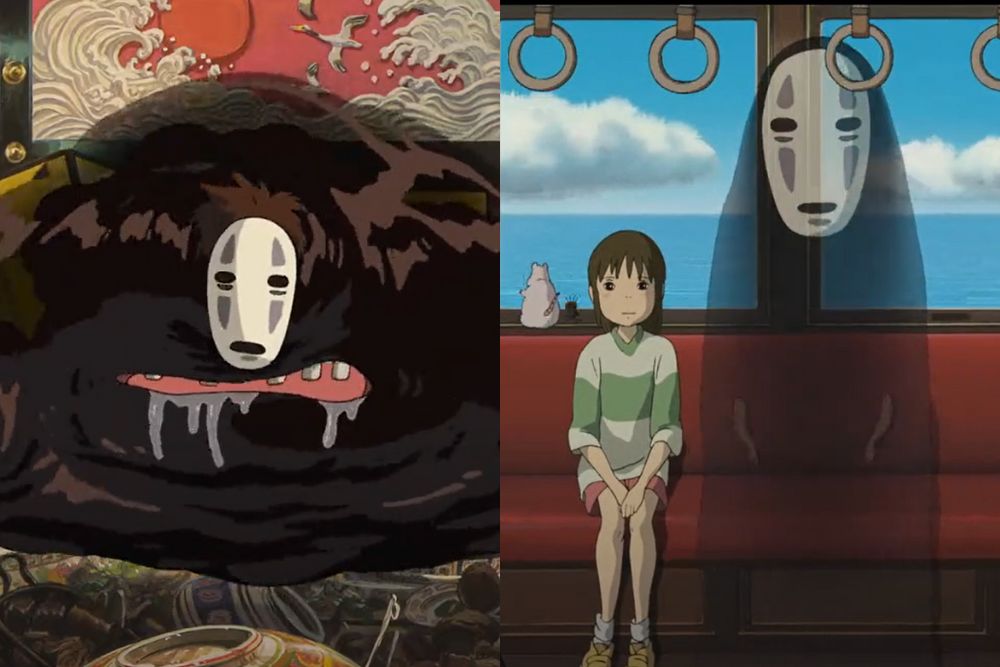

- Hayao Miyazaki’s masterpiece, Spirited Away, vividly portrays the peril of losing one’s name and, by extension, one’s identity. When Chihiro enters the spirit world, the witch Yubaba steals her name to control her. Another character, Haku, has also had his name stolen and forgotten, trapping him in servitude. Their liberation hinges on remembering and reclaiming these true names.

- In the world of Yu-Gi-Oh!, the central plot revolves around the Nameless Pharaoh, Atem, whose quest to recover his forgotten name is inextricably linked to restoring his memories, his full identity, and fulfilling his ancient destiny.

Image credit: Fandom

While these tales may involve elements of fantasy or mysticism, they all share a common theme: the “true name,” or the true, essential self it represents, holds genuine power. Knowing it is often portrayed as the key to gaining power over oneself. This isn’t necessarily about external control, but an inner, psychological, and existential empowerment.

While the ‘true names’ in the above-mentioned narratives typically carry a whisper of magic or myth, their enduring appeal lies in a deeper truth they mirror about our own lives. Specifically, the journey to understand our own self-identity – to connect with that very core of our being – is an endeavor of profound and practical importance. It points towards a more centered, insightful, and potent way of navigating existence.

With this understanding of why such self-knowledge is likened to discovering a powerful ‘true name,’ let us now delve into the specific ways a clearer sense of self may benefit us.

The bridge to meaning, belonging, and authentic living

The value of identity of course is that so often with it comes purpose.

Richard Grant

The desires for meaning, purpose, and belonging – things that make life more than mere existence – are not superficial wants but deeply ingrained human needs. Sociological thought has long underscored our intrinsic need for social integration, not just for support, but to find our unique place and derive meaning within a collective context. When these deep needs go unmet, one is likely to feel adrift, a sense of something vital missing from their life.

Beyond these fundamental drives, there exists a quiet yet powerful human intuition: the sense that our individual existence, in its unique manifestation, should somehow matter. The psychologist Erik Erikson once articulated this profoundly when he wrote:

We all dimly feel that our transient historical identity is the only chance in all eternity to be alive as a somebody in a here and a now.

What does this deep-seated urge to be a ‘somebody’ truly signify for us?

Erikson’s insight points towards the crucial role our felt sense of individual identity plays in imbuing our fleeting lives with personal meaning and resonance. It highlights the unique configuration of awareness and experience that each of us embodies – the specific lens through which we, and only we, encounter the world.

This isn’t about a yearning for public acclaim or extraordinary status, but rather about the intimate, subjective conviction that this particular stream of consciousness, this life that is ‘mine,’ possesses a distinct quality and offers an unrepeatable perspective on existence, regardless of how outwardly modest our circumstances might be.

When we connect with and begin to articulate this personal self-identity, we transform what might otherwise feel like mere biological duration into a vividly lived experience of being a particular individual – someone with a unique narrative-in-progress, a distinct viewpoint that contributes to the human mosaic, and an irreplaceable presence in the here and now. The profound feeling of ‘mattering’ as this specific ‘somebody’ is one of the most powerful wellsprings of meaning we tap into, fueling our engagement with life.

So, how does knowing who we are connect to these fundamental aspirations and affirm this vital sense of being a significant ‘somebody’?

Finding your ‘place’

Knowing yourself – including your core values, unique passions, inherent strengths, and distinct perspectives – is like possessing an internal map, guiding you towards your “place”: a state of authentic alignment in the broader world, within your communities, and in your relationships.

This isn’t about contorting yourself to fit in or conforming to external pressures. Quite the opposite. A clearer self-identity empowers you to seek out and cultivate environments, roles, and connections where your authentic self doesn’t just survive, but can genuinely thrive. It lessens the feeling of being overwhelmed by infinite choices and provides a coherent sense of direction, which in turn fosters a healthy sense of personal agency and perceived control over your life’s journey.

Serving as an internal compass

Self-knowledge makes it easier to resist distractions or influences that are not aligned with your core identity and chosen goals. As such, you become better equipped to prioritize your actions, energies, and commitments. The friction between your desires, actions, and core beliefs is lessened. This alignment is the heart of what it means to live authentically – when your external life begins to more closely mirror the truth of your inner world, instead of being swayed by external expectations, societal scripts, or a “false self” constructed primarily to please others or avoid disapproval.

Cultivating true belonging

When you understand your core identity, you become better equipped to discern what kind of relationships and communities will be genuinely nourishing and supportive. You begin to recognize ‘your tribe’ – those individuals who resonate with your values/ passions, and accept you for who you truly are, fostering an environment of mutual growth.

This stands in stark contrast to attempts to belong made without self-awareness, which are likely to give rise to superficial connections, a lingering sense of alienation even amidst a crowd, or the exhausting charade of maintaining a false persona.

A clear self-identity allows you to show up as you are, paving the way for deeper, more meaningful bonds.

Consider, for example, someone who discovers through dedicated self-reflection that deep empathy and collaborative problem-solving are central to their being. This realization not only steers them towards a career path that feels inherently meaningful (perhaps in mediation, community development, or a leadership style that fosters teamwork) but also guides them towards friendships and groups where these qualities are cherished and reciprocated. The result is, most of the time, a powerful synergy of purpose and belonging.

At the same time, it’s also crucial to recognize the courage of aligned non-belonging. A strong sense of self provides the clarity and fortitude to disengage from groups, relationships, or situations that compromise your core values or authentic self.

This discernment is vital; sometimes, true belonging to oneself and to what matters most means first acknowledging where you don’t belong, thereby freeing you to find or create spaces where genuine connection truly is possible.

Read more: Are You Living or Just Existing? Let’s Find Out!

Better equipped to deal with life’s transitions & disruptions

Life, in its essence, is a dynamic unfolding, rarely a straight or predictable path. It is marked by constant transitions – career shifts, the evolution of relationships, the natural process of aging, moving to new places – and punctuated by unforeseen disruptions like loss, illness, or sudden setbacks. No one is exempt from navigating these currents of change.

While these periods may undoubtedly be challenging, unsettling, and even disorienting, how we weather these storms is significantly influenced by the clarity and resilience of our internal sense of self.

The unfortunate thing is that many of us succumb to a “fragile sense of self” – one that is:

- Overly reliant on external validations: Perhaps your sense of worth is almost entirely tied to your job title, your social status, a particular relationship, or constant approval from others.

- Vaguely defined or poorly understood: You might have a hazy notion of who you are, lacking clarity on your core values, beliefs, or intrinsic strengths.

- Rigid and unable to adapt: Your self-concept might be so fixed that any experience challenging that definition feels like a fundamental threat, making integration of new realities difficult.

- Not deeply rooted in intrinsic values or a stable inner foundation: Your identity might be built more on shifting external factors than on deeply held, internal principles.

When an identity is characterized by such fragility, even predictable life transitions, let alone sudden disruptions, can lead to personal crises – i.e., feeling profoundly lost, overwhelmed, or as if one’s entire world is shattering because the external supports that propped up that identity have changed or disappeared. In fact, many common life problems – such as chronic indecision, a persistent fear of commitment, pervasive dissatisfaction despite outward success, or profound difficulty coping with loss – are frequently rooted in unresolved questions, insecurities, or a lack of clarity about one’s core identity.

Below the level of the problem situation about which the individual is complaining – behind the trouble with studies, or wife, or employer, or with his own uncontrollable or bizarre behavior, or with his frightening feelings, lies one central search. It seems to me that at bottom each person is asking, ‘Who am I, really? How can I get in touch with this real self, underlying all my surface behavior? How can I become myself?’

Carl R. Rogers

So, how does a developed, flexible, and well-understood self-identity help us navigate these challenging waters more constructively?

- Provides continuity & coherence

A strong sense of self offers a stable thread of “me-ness” that persists even when external roles or circumstances change dramatically. It’s the feeling of, “Even though X has changed in my life, I know who I am at my core, and I am able to navigate from that center.”

- Offers a framework for interpretation

When disruptions occur, a clear identity, rooted in your values and life narrative, allows you to make sense of these events in a way that aligns with who you are. Instead of feeling purely chaotic or like a passive victim of circumstance, you have the capacity to frame the experience within your broader understanding of your life’s journey. For instance, a difficult career change might be framed not as a personal failure, but as an unexpected detour that opened new avenues for self-discovery.

- Guides adaptive responses

Knowing your core values and priorities helps you make choices during transitions that are conducive to your long-term well-being (e.g. addressing a conflict calmly rather than reactively, based on awareness of your value for respectful communication). This contrasts with reactive, fear-based, or self-defeating decisions springing from a place of confusion or a threatened ego.

- Fosters resilience & potentially reduces self-sabotage

While not a magic shield against distress, a strong internal compass acts as a significant protective factor. It makes one less prone to prolonged despair or extreme withdrawal (like the phenomenon of hikikomori, where individuals isolate themselves completely – a culturally specific response that nonetheless highlights the dangers of a fractured connection to self and society). A grounded identity provides an internal source of worth and meaning that is less dependent on fluctuating external conditions.

More fulfilling social interactions

In the social jungle of human existence, there is no feeling of being alive without a sense of identity.

Erik Erikson

A robust self-identity is far from a self-absorbed or isolating pursuit. Instead, it is a vital ingredient for enriching one’s social lives and deepening human connections.

The journey inward to know our own depths doesn’t just change how we see ourselves; it fundamentally reshapes our perception of and engagement with everyone around us.

- Authenticity invites authenticity

With self-knowledge comes self-acceptance, and with self-acceptance comes the ability to present one’s genuine self. There’s less need for pretense, less fear of vulnerability. As such, it contributes to creating an atmosphere of safety and trust, encouraging others to lower their own defenses and be more genuine in return.

- More transparent communication

A clearer sense of self inherently facilitates more articulate and honest communication of our own needs, boundaries, values, and feelings. When we know what feels “right” for us, we can express it more directly and constructively. Simultaneously, this inner clarity reduces the tendency to project our own unresolved issues, insecurities, biases, or assumptions onto others – leading to interactions based more on present reality than past baggage.

- Seeing beyond the superficial facades

Being aware of our own complicated nature sensitizes us to that in others. It allows us to look past the immediate roles, labels, and surface-level presentations that often dominate social interactions. We start to see the person behind the ‘difficult colleague’ label, recognizing their potential unseen struggles, their own hidden complexities, or appreciating the unique individuality of a family member beyond our ingrained familial roles and expectations.

In other words, there is now a conscious effort to move beyond snap judgments and societal stereotypes, seeking the human being beneath the exterior. When conflicts arise – as they inevitably do in any relationship – those involved are better equipped to navigate them constructively with a greater capacity for understanding and repair, because they recognize their shared complexities.

It is through such authentic engagement, grounded in a clear sense of self, that we truly ‘feel alive’ in our connections with others, moving beyond the ‘social jungle’ into a space of more meaningful human interaction.

Without understanding yourself, what is the use of trying to understand the world?

Ramana Maharshi

Enriching one’s life

There’s a popular saying, often attributed to Albert Einstein (though its precise origin is debated), that resonates deeply when we consider the importance of realizing our nature:

Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.

Indeed, our sense of self is profoundly shaped by how we understand our own intrinsic nature and how that nature is perceived or judged – both by ourselves and by the world around us. When individuals are primarily seen, or come to see themselves, through a lens that doesn’t match their inherent capabilities and inner landscape (like that fish perpetually assessed on its tree-climbing prowess), the almost inevitable result is a distorted self-image, diminished self-worth, and a life lived with a nagging sense of inadequacy, frustration, or simply feeling fundamentally “miscast.”

History offers glimpses of this. Those like Einstein himself, or Thomas Edison, are known for their unconventional ways of thinking and learning – aspects of their identity – that initially clashed with the rigid educational or societal systems of their time, leading to them being misunderstood or undervalued. Their eventual flourishing often coincided with finding or creating environments where their unique, innate abilities could finally be expressed and recognized. They found their “water,” so to speak.

At our core, most of us are engaged in a quiet, often unconscious, quest for happiness, contentment, and a life that feels genuinely worthwhile. Many of our actions, from the grand to the mundane, are, in some way, aimed at moving us closer to these states of inner well-being.

If we genuinely seek to enrich our lives – to move beyond mere existence into a state of joyful participation – then reflecting on our true self-identity becomes not a peripheral pursuit, but an absolutely essential one. It’s about discovering our inherent strengths, our unique qualities, and pinpointing what truly makes us feel alive and aligned.

How self-identity serves as the fountainhead of a more abundant life:

- A source of peace

The journey of self-discovery helps clarify our core values, true motivations, innate talents, and even our recurring emotional and behavioral patterns. When you know the “why” behind your feelings and actions, much of the inner turmoil born from confusion or self-judgment begins to dissipate, leading to greater inner peace and contentment. On the other hand, a clear and internally harmonious self-concept acts as a buffer against negativity and promotes a more optimistic and resilient outlook on life.

- A path to joy

When our choices and actions align with our inner truth, it results in a powerful source of deep-seated joy and inner harmony. The constant, draining friction of living in a way that feels “off” lessens, making space for a more resonant and satisfying life experience.

- Unlocking potential & redefining “success”

Connecting back to the fish example, when you understand your “element” – the environments, activities, and ways of being that align with your core identity – you naturally gravitate towards paths where you not only perform well but also experience genuine engagement, flow, and a sense of purpose. This is where true enrichment lies. “Success,” in this light, is less about conventional material accumulation or external accolades, and far more about personal fulfillment, a sense of contribution, and spiritual well-being.

Example: Someone who realizes through self-reflection that their core identity thrives on nurturing and guiding others might find profound happiness in roles like teaching, coaching, mentoring, or community care, regardless of the external prestige attached.

Another individual, whose identity is deeply interwoven with intellectual curiosity and problem-solving, discovers a rich and joyful life through continuous learning and tackling complex challenges, perhaps in unconventional fields.

The foundation for transformation & transcendence

It is not the accumulation of extraneous knowledge, but the realization of the self within, that constitutes true progress.

Okakura Kakuzo

Image credit: Studio Ghibli

Do you recognize the enigmatic figure of No-Face (Kaonashi) from Studio Ghibli’s animated masterpiece, Spirited Away? His story offers a powerful illustration of the search for identity and the potential for change.

Initially, Kaonashi is a silent, shadowy being, seemingly without a distinct identity of his own. When he enters the spirit world, he discovers that he can gain attention and apparent acceptance by producing gold. However, this path leads him to become increasingly monstrous, consuming others and absorbing their negative traits – their greed, their voices, their superficial desires. Without a stable inner core, he becomes a distorted mirror of his environment’s dysfunctions, his shape and behavior alarmingly fluid and reactive.

Yet, Kaonashi’s story doesn’t end there. The turning point comes through his interaction with Chihiro, the anime’s protagonist. Her genuine kindness, her refusal to be swayed by his material offerings, and her simple acceptance of him, even in his monstrous state, offer a different kind of reflection – one not based on greed or fear.

This marks the beginning of Kaonashi’s transformation. Eventually, he finds a measure of peace and contentment in a simpler existence with the witch Zeniba.

Image credit: Studio Ghibli

Kaonashi’s story, I believe, is a potent allegory for the human search for identity: without a robust core self, we are highly susceptible to external influences, societal pressures, and the hollowness of chasing validation. Yet, it also beautifully hints at our innate potential for transformation when we are touched by authenticity and begin the work of cultivating our own.

In today’s world, the emphasis is, unfortunately, so heavily skewed towards external markers of success – career achievements, material wealth, social status – that the crucial, often quieter, work of inner self-understanding is completely overshadowed. When personal development is pursued primarily as a means to external ends, without a foundation, many find themselves chasing goals that don’t align with their deepest nature. The result? A subtle, pervasive sense of “facelessness” – a feeling of being adrift despite apparent success, unfulfilled even amidst accomplishments, or constantly wearing a mask that doesn’t quite fit. Such a state may manifest as burnout, chronic dissatisfaction, an existential vacuum, or a susceptibility to adopting fleeting personas in a desperate search for something real.

A clearly understood self-identity, however, is not a static achievement to be displayed. Instead, it serves as a dynamic and essential launchpad for more profound levels of human experience:

- Genuine transformation (beyond mere coping)

True personal transformation isn’t just about changing habits or coping more effectively with stress. It involves a fundamental, often lasting, shift in our perspective, our character, and our very way of being in the world. It’s an evolution of the self at a deep level.

Knowing your core identity – your deeply held values, beliefs, ingrained emotional and behavioral patterns (both helpful and hindering), and your most heartfelt aspirations – provides the foundation needed to consciously engage in this transformative work. It allows you to realize what parts of you may need healing or integration (e.g. a deep-seated fear of intimacy), what latent potentials need cultivating (e.g. a long-dormant passion for art), and what path you must forge towards becoming a more whole and integrated version of yourself.

- The path to self-actualization

Humanistic psychology, particularly through thinkers like Abraham Maslow, introduced the concept of self-actualization – which refers to the intrinsic human drive to realize one’s fullest unique potential, to become everything one is capable of being.

A clear and evolving self-identity acts as the indispensable compass on this journey. It helps illuminate what those unique potentials are for you. Without knowing who you are at your core – your distinct talents, passions, and way of seeing the world – the quest to ‘actualize’ that self remains an abstract ideal, unguided and often out of reach.

- Opening to self-transcendence

Beyond even self-actualization, a robust self-identity serves as the gateway to self-transcendence. This involves experiences or states of consciousness where we move beyond a narrow focus on our individual ego or personal story to feel deeply connected to something larger – be it humanity as a whole, the natural world, universal principles of love and compassion, or what one might perceive as a spiritual dimension.

Does that sound a little counterintuitive? As paradoxical as it may seem, a well-integrated and secure sense of self is actually the firmest launching pad for such experiences.

When the ego is not fragile, constantly seeking validation, or terrified of losing its perceived boundaries (because identity is relatively stable and authentic), it is more ready to ‘let go’ and expand into these larger connections without the fear of annihilation or fragmentation. This isn’t about losing a self you never truly knew, but about a mature, grounded self finding its place and connection within a vaster context.

Have you ever been through moments of profound awe in nature, a deep altruistic love that moves one to selfless service, peak experiences of creative flow where the sense of a separate self dissolves, or the sense of unity and interconnectedness often described in various contemplative and meditative practices?

I believe that most of us have, at least once in life. Just recall them, and you should be able to understand.

These moments of self-transcendence are not just fleeting curiosities; they can be profoundly meaningful, bringing with them a sense of expansive joy, deep inner peace, and a powerful feeling of connection that enriches our self-understanding and interconnection with the larger current of life. They offer a glimpse beyond our everyday worries and limitations.

…

The journey into self-identity, as we’ve begun to see, is therefore far more than a mere intellectual pastime or a dive into abstract philosophy; it is an exploration central to the human experience. Embracing the quest to know ourselves is fundamental to living more purposefully and harmoniously.

When to Think About Self-identity

The journey of understanding oneself is, in many ways, a quiet hum beneath the surface of our daily lives – a lifelong practice that can enrich any moment we choose to engage with it. There’s never truly a ‘wrong’ time to turn our attention inward and ponder the question of who we are.

However, life has a way of presenting certain periods, distinct internal experiences, or significant external events that act as powerful catalysts. These moments may nudge us, sometimes gently, sometimes quite forcefully, towards a more focused and intentional way of living.

Internal signals

Often, the first prompts to explore our identity come from subtle (or not-so-subtle) shifts within our own inner landscape. These are the feelings, thoughts, and recurring patterns that suggest a need to reconnect with, or perhaps redefine, who we are:

- A persistent sense of being lost, adrift, or disconnected from yourself; a feeling that you don’t truly know who you are at your core, or that the ‘you’ you present to the world isn’t the ‘you’ within.

- Finding yourself questioning long-held beliefs, values, or life philosophies, accompanied by an unsettling uncertainty about what new principles might replace them.

- A growing, nagging feeling that your daily life, your work, or your actions lack authenticity or no longer align with what’s “in here”; experiencing a persistent disconnect between who you feel you are (or aspire to be) and the way you are currently living.

- Struggling to define your place or role in key areas of life – be it in your relationships, your career, or your broader community; feeling unsure of where you truly fit in or what your unique contribution might be.

- Finding yourself engaging in a deep re-evaluation of past choices and your future direction.

- Experiencing chronic indecisiveness, especially about significant life choices, which typically stems from a lack of clarity about your personal priorities, core values, and deepest desires.

- Frequently feeling like an imposter, as if you’re wearing a mask or merely performing a role for others.

- An uncomfortable, lingering sense of inner emptiness, restlessness, or a vague yet persistent feeling that “something is missing,” even when your external circumstances might appear objectively fine or successful.

- Noticing a pattern of seeking excessive external validation or being overly sensitive to criticism, which may indicate an unstable internal sense of self-worth that relies too heavily on outside approval.

- A nagging feeling of being “stuck,” stagnant, or unfulfilled, often coupled with a clear desire for growth or change but a frustrating uncertainty about the path forward.

- A yearning for deeper meaning, a more profound sense of purpose, or a desire to make a more significant contribution to the world.

These cues are like messages from your inner self, gently (or insistently) inviting you to pause and look more closely.

Self-identity: Who am I?

External triggers

Beyond the above-mentioned internal stirrings, life itself presents numerous junctures – natural developmental stages, significant events, or shifts in our external world – that often serve as powerful prompts for identity exploration:

- Adolescence & young adulthood: This formative period is almost defined by the quest for identity, as individuals grapple with “Who am I?” and “Where am I going?” amidst crucial decisions about education, career paths, values, and forming independent relationships.

- Major career shifts: Whether starting a new career, receiving a significant promotion (or demotion), experiencing job loss, or transitioning into retirement, our professional lives are often deeply entwined with our identity, and changes here are very likely to trigger re-evaluation.

- Significant relationship changes: The beginning or end of a serious romantic relationship, marriage, divorce, becoming a parent, or children leaving home (the “empty nest” phase) all redefine our roles, our connections, and consequently, our perceptions of self.

- Relocation: Moving to a new city, region, or even a different country strips away familiar social supports and cultural contexts, often necessitating a re-examination of who we are without those accustomed backdrops.

- Major achievements or setbacks: Paradoxically, both significant successes (which might lead to a surprising “Is this all there is?” feeling) and notable failures are capable of triggering deep questions about our identity, values, and the true meaning of our life path.

- Loss and bereavement: The death of a close loved one inevitably shakes our world, often calling for reflection on our own life, values, and stance in the face of mortality.

- Health crises or significant illnesses: Confronting physical limitations or the fragility of life frequently leads to a re-evaluation of priorities and a deeper search for meaning and self beyond physical capabilities.

- Midlife transitions: Commonly experienced between the ages of (roughly) 40 and 60, this period typically involves individuals reassessing their lives, accomplishments, and future goals, asking “Is the life I’ve built truly reflective of who I am or want to be for the next chapter?”

- Exposure to new, diverse perspectives: Encountering different cultures, challenging ideas, or alternative lifestyles (through travel, education, new friendships, or even compelling books and media) may cause some of us to re-evaluate our own ingrained assumptions and culturally conditioned aspects of our identity.

- Broad societal shifts or crises: Major global or national events – such as pandemics, significant economic recessions, profound social justice movements, or rapid technological changes (as we’re seeing these days) – can disrupt our sense of normalcy and encourage a collective and individual reconsideration of our place, our values, and our identity within a rapidly changing world.

These moments, whether quiet internal nudges or significant external shifts, are more than just life events; they are potent invitations to engage more deeply with our inner world. Recognizing when these calls for self-reflection arise naturally leads us to the next essential step: exploring more fully what this ‘self-identity’ truly encompasses.

Defining Self-identity: Components, Theories & Frameworks

You’re likely pondering, as many have before:

- What truly determines our self-identity?

- What are the core components that define who we are?

- How is our sense of self built and structured?

These questions, while seemingly direct, have no simple, single answer. Indeed, the enigma of identity has captivated thinkers and seekers across various fields for centuries.

Philosophical inquiry

For millennia, philosophy has been the primary arena where humanity has wrestled with the deepest questions about what it truly means to be a self, to exist as a distinct “I” in this vast universe.

One of the most enduring puzzles philosophers explore is personal identity over time: what makes you, the person reading this, the same individual who existed yesterday, or as a child in an old photograph, despite all the changes you’ve undergone?

Early on, thinkers proposed several core ideas about this enduring “you”:

- The Soul view (also referred to as the “Simple view”): Many ancient thinkers, like Plato and Socrates, and later philosophers like René Descartes (with his famous “I think, therefore I am”), suggested that our true essence lies in an immaterial soul or a persistent thinking mind – a core that remains constant even as the body changes.

- The Bodily view: Others have tied identity more closely to our physical being – specifically, the continuity of our body, or perhaps primarily our brain.

- The Psychological view: Philosophers like John Locke argued that identity is found in psychological continuity – an unbroken chain of consciousness and memory. You are “you” because you remember being you in the past.

These foundational ideas, each with their own complexities and challenges (e.g. what happens if memories are lost, or if consciousness could theoretically be duplicated?), open up a wider philosophical dialogue about the self.

◆ The nature of our perceived Self: Fixed core or flowing river?

Do we have a stable, unchanging core, or is the “self” more like a constantly shifting current?

Is the self something to be found, or something that is always in process, always being redefined by experience?

While the idea of psychological continuity, as championed by Locke, gives us a strong sense of a continuous self through our linked memories and awareness, other thinkers have pushed further. For instance, Immanuel Kant argued that for us to even experience our lives coherently as our own, there must be an underlying “unity of consciousness“. He wasn’t necessarily saying what this self is made of, but that our mind actively structures our perceptions to create a unified experience of being an “I” through all the flux of sensations and thoughts.

In contrast, philosophers like David Hume looked inward and declared he could find no such single, stable self – only a fleeting “bundle of perceptions,” a continuous parade of thoughts, feelings, and sensations. From his viewpoint, the “I” we feel so sure of might be more of a useful illusion, a story we tell ourselves, rather than a fixed entity.

From an Eastern perspective, Lao Tzu claimed that the true self is found not in a rigid, ego-defined identity, but in harmony with the Tao – the natural, flowing Way of the universe. For this, one needs to let go of fixed notions of “me” and instead embrace simplicity and spontaneity, aligning with this cosmic current.

More recently, philosopher Derek Parfit argued for a “reductionist” view, suggesting that what truly matters for our ongoing existence are varying degrees of psychological connection to past and future selves, rather than a deep, indivisible, all-or-nothing “identity.”

◆ The Self we actively shape: Identity through creation, choice, and connection

Regardless of whether there’s a fixed core or constant flux, various thinkers emphasize our active role in shaping who we become, often through our choices and relationships.

- Self-creation and becoming

- Friedrich Nietzsche urged individuals to “become what you are.” For him, identity isn’t about passively discovering a pre-packaged self, but an active, often challenging, process of self-creation and self-overcoming. It involves questioning societal norms, forging one’s own values, and embracing the fullness of life to realize one’s unique potential.

- Existentialist philosophers took this idea of self-creation even further. Jean-Paul Sartre argued that “existence precedes essence” – meaning we are born into the world without a predetermined purpose or identity. We simply exist, and then, through our choices and actions, we define who we are. Self-identity, for Sartre, is a continuous project of self-making, carrying with it immense freedom and profound responsibility.

- Albert Camus, similarly, explored how we can forge meaning and define ourselves through a conscious “revolt” against a seemingly absurd or meaningless universe, by embracing all life has to offer and the dignity of our personal struggle.

- The Relational Self

- Certain schools of thought highlight that “who I am” is deeply formed by “who I am WITH.” In ancient China, Confucius taught that the self is not an isolated entity but is cultivated and realized through our social roles, responsibilities, and the quality of our harmonious relationships with family, community, and society.

- Martin Buber shared the same perspective in his concept of the “I-Thou” relationship. He believed that our “I” truly comes into being and finds its authentic expression not by treating others as objects (“I-It”) for our own purposes, but through genuine, mutual, and present encounters with another “Thou.” Our identity is awakened and deepened in the space of authentic connection.

- Hegel suggested that our identity is partly shaped by our understanding of what we are NOT, through our dynamic relationship with “otherness” or “non-identity.” We define ourselves, in part, by distinguishing ourselves from the world and others around us. Without this “non-identity,” the notion of “identity” itself would become empty and meaningless, as there would be nothing from which to distinguish it. At the same time, Hegel also argued that things are inherently self-contradictory and constantly changing. For instance, a seed is a seed, but it also contains within it the potential to become a plant; in a sense, it is both “seed” and “not-seed” (plant) simultaneously in its potentiality and process of becoming.

As you may see, this brief journey through diverse philosophical landscapes might initially seem to offer more questions than answers about self-identity. And perhaps that is philosophy’s greatest gift to one’s self-discovery journey.

It doesn’t hand us a neat definition but instead equips us with critical thinking tools to assess our own assumptions about who we are. It challenges us to look beyond superficial appearances and societal pronouncements.

Engaging with these ideas and reflecting on how they resonate with our own experience provide a powerful way to live a more conscious, examined, and ultimately, self-aware life.

Religious and spiritual traditions

Beyond philosophy, humanity’s diverse religious and spiritual traditions offer another set of lenses through which to explore the nature of self-identity. These ancient paths, often rooted in sacred narratives, personal faith, mystical experiences, and communal practices, provide rich frameworks for realizing who we are in relation to the divine, the cosmos, and our deepest human purpose.

◆ Unveiling your essential nature: Soul, spirit, and innate potential

Many spiritual traditions point towards a deeper, often enduring or divine, core of our being – an essential self that lies beneath the surface of our everyday personality.

- In the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), there’s a shared belief in the existence of an inner essence, often termed the “soul”. It is generally considered the seat of our consciousness, moral awareness, and is widely held to endure beyond physical life. Our identity, from this perspective, is intrinsically linked to this soul, our connection to God, and the idea of being created in a divine “image,” suggesting an inherent worth and spiritual potential.

- Hinduism proposes the concept of Atman – often translated as the individual soul, the true Self, or the innermost essence of a living being, distinct from the fleeting ego. A central quest is to understand the Atman’s relationship to Brahman, the ultimate, all-pervading Reality or Universal Consciousness. Some schools teach the ultimate identity of Atman and Brahman (“You are That”), implying our truest Self is one with the Absolute.

- Across various spiritual insights, there’s often a sense of an innate pure potential or “divine spark” within each person – something intrinsically good, wise, or capable of awakening, waiting to be uncovered and realized.

◆ Seeing through illusions: The Self as process and the path to freedom

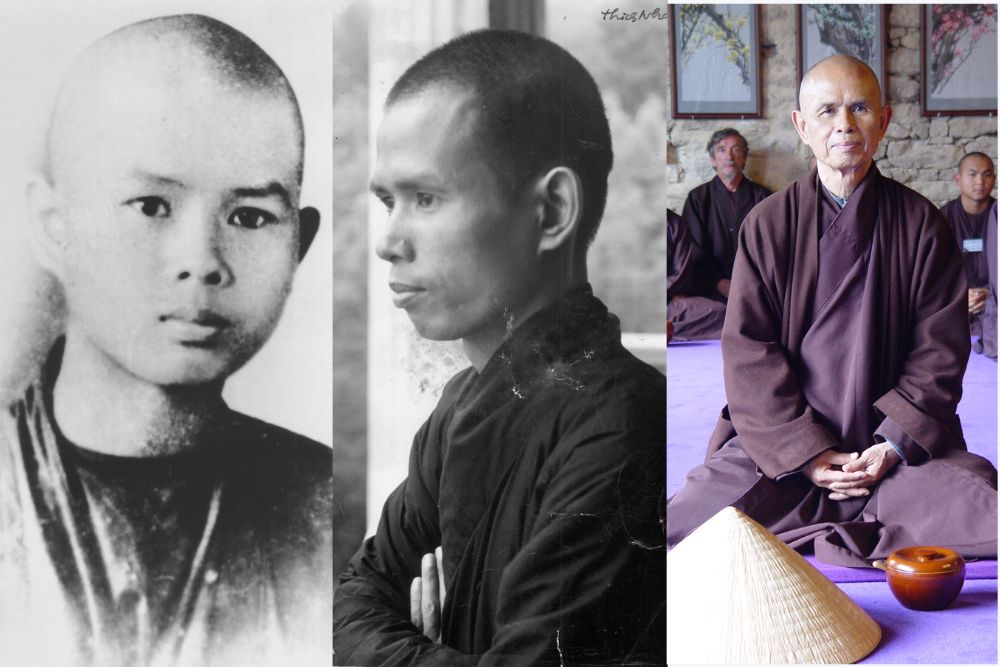

Contrasting with views of an eternal soul, some traditions invite us to see through the illusion of a fixed, independent self as a direct path to liberation. For example, Buddhism is known for its teaching of Anatta (no-self or non-essential self). This doesn’t mean we don’t exist, but rather that there’s no permanent, unchanging, independent “I” or soul at our core. What we conventionally call our “self” is understood as a dynamic, ever-changing process, a temporary coming-together of five “aggregates”: our physical form, feelings, perceptions, mental formations (like thoughts and intentions), and consciousness. This “self” is characterized by impermanence and interdependence.

The deep insight into anatta is not a denial of our lived experience but a way to free ourselves from suffering, which arises from clinging to the idea of a solid, separate, and permanent ego. While we DO use a “conventional identity” (our name, roles) to navigate the world, wisdom lies in recognizing its constructed and transient nature.

◆ Identity in communion: The Self defined by connection

Many spiritual worldviews emphasize that self-identity isn’t found in isolation but is realized and finds its meaning through our connections – to the Divine, to our community, to nature, and to all of existence.

- In Abrahamic faiths, identity is typically shaped by one’s covenant and relationship with God, and also by belonging to a community of faith that shares rituals, values, and a sacred history.

- Many Indigenous spiritual perspectives promote a sense of self interwoven with family, community, ancestors, the natural environment, and the spirit world. Here, identity is less about solitary autonomy and more about one’s place, role, and responsibilities within this vast web of relationships.

- In Hinduism, the concept of dharma (one’s righteous duty, ethical path, or intrinsic role) shapes the individual’s place within the cosmic and social order, guiding the Atman’s journey.

- The mystical currents within many religions (like Sufism in Islam, Christian mysticism, Kabbalah in Judaism, and various Yogic paths) often describe the spiritual journey as a quest for union – a merging of the individual self with the Divine or Universal Consciousness, transcending the illusion of separateness. For this purpose, direct experience is key – and practices such as meditation, contemplative prayer, deep introspection, and ethical cultivation may come in handy.

Who am I? Not the body, because it is decaying; not the mind, because the brain will decay with the body; not the personality, nor the emotions, for these also will vanish with death.

Ramana Maharshi

While the specific beliefs, languages, and practices of religious and spiritual traditions vary immensely, they share a universal thread: a recognition of the importance of realizing the nature of the self. More than just definitions of identity, they provide time-honored pathways and supportive communities that guide individuals not only to understand who they are – but also to TRANSFORM or TRANSCEND limited, ego-bound notions of self.

In doing so, they help us align with a deeper sense of spiritual purpose, meaning, and our connection to a reality far vaster than our individual experience.

Psychological science

Unlike philosophy and spiritual traditions, psychology offers an empirical lens on self-identity, aiming at its structure, development, and how it functions in our daily lives. Rather than focusing on what makes us the same enduring entity across decades (numerical identity), psychology typically explores our qualitative identity: the rich and evolving content of our self-concept, personality, and social place. It asks:

What key characteristics, roles, beliefs, relationships, and group memberships (as we’ll see below) make up our perceived sense of ‘who I am’ right now, and how do these elements interact to shape our experience?

From a psychological viewpoint, our sense of self isn’t a single, monolithic entity but is understood to be comprised of various intersecting aspects that together contribute to our overall identity.

- Personal characteristics: Our enduring personality traits (like introversion or conscientiousness), unique abilities, and learned skills.

- Social & demographic categories: Our age, gender identity, sexual orientation, ethnicity, race, nationality, and cultural background.

- Roles & relationships: The parts we play in our families, friendships, professional lives, and communities.

- Beliefs & values: Our guiding principles, moral frameworks, spiritual or philosophical outlooks.

- Interests & lifestyle: Our passions, hobbies, and how we choose to live.

- Socioeconomic status: Our social class and economic standing, which can influence opportunities and self-perception.

Over the years, various frameworks have been proposed to shed light on how these facets come together.

◆ The inner world: From unconscious stirrings to authentic expression

Psychologists have long been fascinated by the layers of the self, including those that lie beneath our immediate awareness, and our innate drive towards feeling real and authentic.

- Early psychoanalytic thought, pioneered by Sigmund Freud, while not using our modern term “self-identity,” laid crucial groundwork by highlighting the influence of the unconscious mind and early experiences in shaping our inner self and personality, often through internal conflicts that we continue to navigate.

- Carl Jung expanded this exploration with concepts like the Persona (our social mask) and the Shadow (our repressed or disowned aspects). He saw the journey of individuation as a lifelong process of integrating these varied parts to become a more whole, unique, and authentic Self – the regulating center of our psyche striving for wholeness (which is sometimes referred to as the “inner God”).

- Psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott proposed the need to distinguish between the True Self and the False Self. The former, he suggested, emerges from our spontaneous, genuine experiences and our innate sense of aliveness. The latter develops as an adaptive (and sometimes overly rigid) shield, a way to comply with external demands, which may, in some cases, lead to a painful disconnect from our core sense of reality and authenticity. The quest for identity, from his view, involves nurturing and allowing more space for that True Self to express itself.

◆ The journey of becoming: How identity develops and takes shape

Various psychological studies have demonstrated that our sense of self isn’t static; rather, it constantly evolves, particularly through distinct life stages and processes.

- Erik Erikson’s model of psychosocial development highlights Identity vs. Role Confusion as a critical stage, especially during adolescence. This is a period of intense exploration where individuals grapple with “Who am I?” by trying out different values, beliefs, and roles to forge a cohesive and stable sense of self that integrates personal characteristics with social and cultural realities.

- Building on this, James Marcia described different identity statuses (like identity achievement or moratorium), illustrating the varied paths individuals take in exploring possibilities and making commitments. As such, identity formation is an active, not always linear, process.

◆ The conscious “I”: Our perceptions, aspirations, and the drive to grow

Beyond developmental stages, psychology also examines how our conscious experience, self-perception, and inherent desire for growth contribute to our identity.

- William James distinguished between the “I” – the active, experiencing subject, the sense of being a conscious agent – and the “Me” – the self as it can be known and reflected upon, comprising our material, social, and spiritual aspects. His theory highlights both our awareness and the content of that awareness in forming our identity.

- Humanistic psychologists like Carl Rogers emphasized the self-concept (our organized perceptions and beliefs about ourselves) and the importance of congruence. When our ideal self (who we’d like to be), our perceived self (how we see ourselves), and our actual experiences align, we experience greater authenticity and psychological well-being.

- Abraham Maslow, with his Hierarchy of Needs, viewed self-actualization as our highest drive: the ongoing unfolding of our unique potentials. This journey is deeply tied to knowing and living from an authentic self-identity, as it requires us to understand our genuine capacities and inner callings.

◆ The Self in its worlds: Social connections and life’s interacting domains

Psychology also underscores that identity is significantly shaped by our social context and can be understood as structured across different life areas. The Social Identity Theory, developed by Henri Tajfel and John Turner, illuminates how our membership in various social groups (based on nationality, profession, shared interests, etc.) becomes a fundamental part of “who I am.” It explores the psychological processes by which we categorize ourselves and others into “in-groups” and “out-groups,” and how this social identification influences our self-esteem, attitudes, and behaviors. In other words, it is about the mechanisms by which “we-ness” shapes our individual sense of self.

Social Identity Theory by Henry Tajfel, 1979 (source: ResearchGate)

To further understand how various life aspects contribute to one’s identity, several frameworks have been proposed. For instance, Hilarion Petzold’s model views identity as resting on several key interacting life “pillars” – including one’s physical and mental well-being, social network and roles, work and achievements, material context, and guiding values and beliefs. These domains all contribute to our comprehensive sense of who we are.

Self-identity hierarchical framework (Shavelson, Hubner, & Stanton; source: ResearchGate)

So far, what psychological science reveals with increasing clarity is that our self-identity is an incredibly complex construct. It is continuously shaped by an ongoing interplay of the inner world – our thoughts, emotions, memories, and even our biology – and the outer world, including our social interactions, cultural upbringing, and major life experiences. While the self is intricate, it is also, to a significant degree, knowable and capable of growth.

Contemporary academic lenses

Our exploration of how identity is defined wouldn’t be quite complete without considering the perspectives emerging from fields like sociology and cultural studies. Various modern theories encourage us to see our self-identity not just as an internal psychological construct, but as something dynamically shaped by, and in turn shaping, the world around us (i.e. our broader social and cultural contexts). Specifically, many aspects of who we believe we are – from certain personal characteristics to the roles we inhabit – are influenced by the cultural “blueprints” we are born into.

Examples:

- In many societies, the ‘blueprint’ for success might heavily emphasize certain professions like medicine or law, subtly guiding young people towards these paths, sometimes irrespective of their innate passions.

- Similarly, cultural norms – like whether it’s ‘acceptable’ for men to show vulnerability or for women to express anger – can deeply influence which emotions we acknowledge as part of our identity and which we learn to hide, even from ourselves.

Furthermore, much contemporary academic thought suggests that we might embody different facets of ourselves in different contexts – and that our understanding of who we are is open to ongoing reinterpretation and redefinition throughout our lives.

What does it mean?

- You might have observed this in your own life: perhaps a more assertive, professional facet of you emerges at work, while a more playful, relaxed facet appears with close friends. These aren’t necessarily contradictions or inauthentic masks, but rather valid expressions of a complex self adapting and responding to changing situations.

- An identity largely defined by, say, a specific career in one phase of life can definitely be redefined later. Think of someone who, for decades, identified primarily as a ‘corporate manager.’ Later in life, perhaps through discovering a passion for pottery (a ‘new passion’), becoming a grandparent (a ‘new role’), or gaining profound perspective from overcoming an illness (a ‘new insight’), their primary sense of self might authentically shift to ‘artist,’ ‘nurturing elder,’ or ‘advocate for mindful living.’

By adopting such a fluid view, we are free from the pressure of having to find or adhere to one single “true self”, and instead encouraged to embrace humanity’s complexity and capacity for growth.

The Nature of Self-identity: Exploring Its Characteristics

The quest to understand who we are, as we have explored previously, certainly admits many approaches. Empirical avenues, drawing from psychology, neuroscience, and sociology, offer valuable data, illuminating observable patterns, cognitive mechanisms, and the societal currents that shape us. Simultaneously, subjective pathways, typically walked by philosophers, spiritual seekers, and indeed anyone engaged in deep self-reflection, invite us into the inner landscape of consciousness, personal meaning, and the immediate, felt sense of being.

While both these lenses present crucial insights, our focus here will be more on the subjective character of self-identity. My own conviction, guiding this choice, is that for the deep work of self-discovery and fostering genuine personal transformation, an accumulation of external facts or theories, while helpful, can only take us so far.

There’s an old piece of wisdom that says, ‘You can lead a horse to water, but you can’t make him drink.’ True, lasting changes often spring from that internal ‘drinking’ – the direct, personal engagement with, and felt realization of, the nature of our own self.

With this spirit, let us now consider some of the self’s key characteristics, shall we?

Multifaceted

Do you ever feel like you’re more than just one single, consistent “you”? Like, there are different versions of yourself that emerge in different situations, or even coexist within you simultaneously?

This sense of inner multiplicity is a common human experience (I’m telling you, this is what I feel about myself – and it has baffled me from time to time), and it points to a fundamental characteristic of our self-identity: its multifaceted nature.

In the anime Yu-Gi-Oh! (one of my favorites), the main character, Yugi Mutou, shares his body and consciousness with the spirit of an ancient Pharaoh, Atem. Yugi is depicted as timid and kind, while Atem is remarkably confident, strategic, and imbued with a powerful sense of justice.

Even though the story depicts them as two separate entities, many people have pointed out that the relationship between Yugi and Atem can be interpreted metaphorically. Specifically, they represent two potent, sometimes contrasting, aspects or ‘faces’ of a single individual. They are like:

- Two sides of the same coin: Distinctive, yet complementary facets that form a more complete core being.

- Manifestations of a persona: Different aspects emerging in response to varying circumstances or our own developmental needs – one representing hidden potential, the other perhaps growing empathy.

- A collaborative whole: The two are interdependent – they learn from each other, compensate for initial limitations, and together contribute to a more effective and integrated self.

Image credit: Toei Animation

This notion of holding multiple aspects within a single being isn’t just the stuff of fantasy; indeed, studies have demonstrated that it is an undeniable part of many people’s sense of self.

From a subjective viewpoint, our self-identity rarely feels like a monolithic block, unchanging and simple. Instead, it’s more like a rich composition – formed from our various roles (as a parent, a professional, a friend, a student), passions (the artist, the activist, the quiet observer within us), relationships, treasury of memories, evolving beliefs and values, and so on.

Identity is never singular but is multiply constructed across intersecting and antagonistic discourses, practices and positions.

Stuart Hall

◆ Many facets, one lived experience?

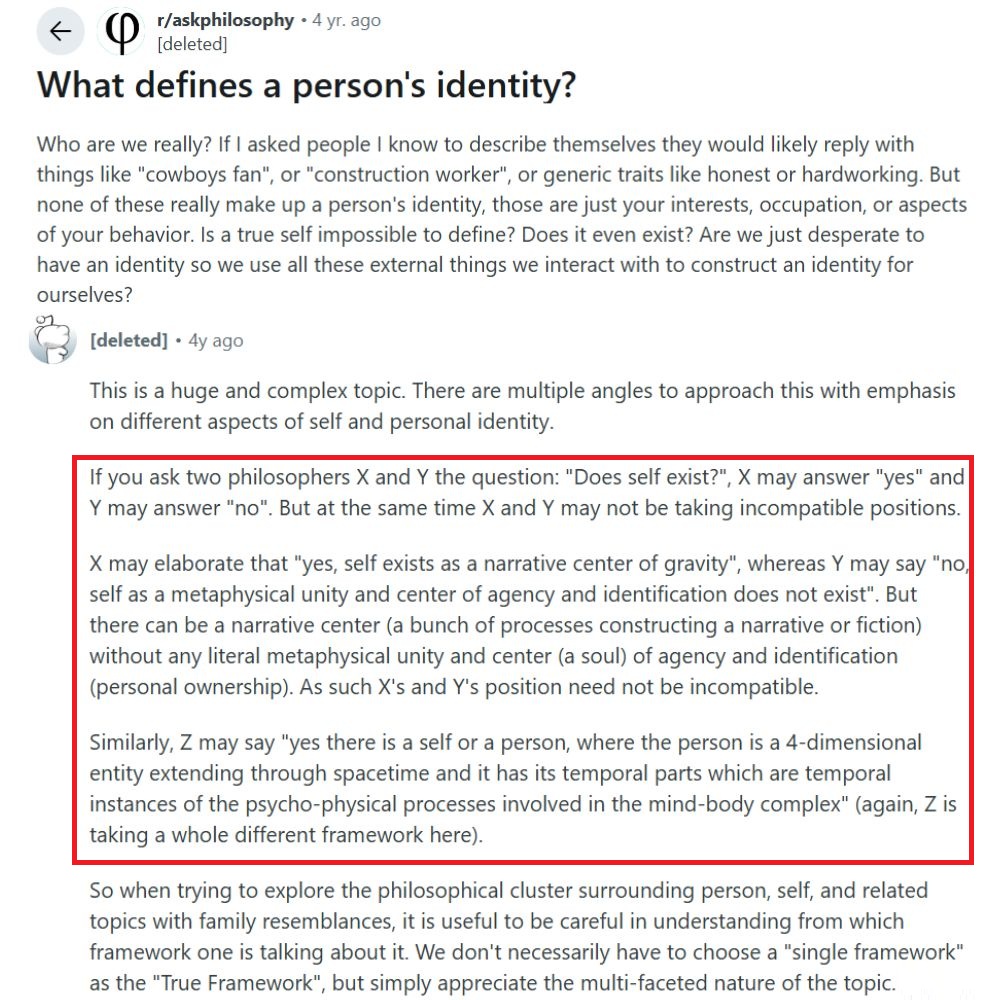

As mentioned previously, philosophers and scientists have long debated the ultimate nature and existence of a singular, unified ‘Self.’ Some theories point to an enduring core entity; others describe a bundle of processes; and some even question the existence of any fixed metaphysical self at all.

For our self-discovery journey, perhaps a more immediate and resonant question isn’t whether a single, ultimate ‘Self’ with a capital ‘S’ exists in one particular metaphysical sense, but rather: How do we experience and integrate our undeniably real and impactful sense of having multiple facets, roles, and even seemingly different ‘selves’ within us?

When I was doing research on the topic, I came across an interesting online discussion that I would like to share here:

What defines self-identity (source: Reddit)

As you may see, different frameworks describe the ‘self’ in ways that seem contradictory – one might speak of a ‘narrative center,’ another might define a person as a ‘four-dimensional spacetime entity,’ while another might deny any ‘metaphysical unity.’ Yet, as the discussant pointed out, these descriptions aren’t necessarily incompatible. They might simply be highlighting different aspects or levels of analysis of our complex being, much like describing a mountain from its base, its peak, or its geological composition offers different, yet all valid, facets of the same mountain.

Just reflect on your own life: you might embody a playful, spontaneous self with your children, a focused and analytical self in your professional work, and a quiet, reflective self in moments of solitude. These aren’t necessarily separate “people”, but different valid facets of your identity that come to the fore, each with its own way of feeling, behaving, and relating to the world.

◆ Navigating our many (sometimes conflicting) sides

Now, I’m not quite sure if this applies to you, but I myself can relate strongly to this internal experience of multiplicity. Many times, I find myself:

- Thinking or feeling things that seem contradictory at the same time.

- Behaving quite differently depending on who I’m with or what a situation demands (for instance, being an assertive manager at work but a more reserved listener in a new social group).

- Having an ‘inner critic’ voice that seems to be in constant debate with an ‘inner encourager’ or a more compassionate self.

How about you?

Have you ever been through a situation in which your deeply held values came into conflict with each other? When life presented you with difficult choices, and picking whichever would mean honoring one cherished value at the cost of another? (e.g. the tension between a desire for personal freedom and adventure – which is one facet of self – and the longing for deep, committed relationships and stability – which is another facet)

When our personal values pull us in varying directions, some may question if it is a sign of a flawed or incoherent identity. However, I myself believe that it is a direct manifestation of our multifaceted richness.

Realizing that these tensions arise from the diverse and valid parts of who we are will enable us to approach difficult choices with more self-compassion, curiosity, and thoughtful deliberation, rather than self-criticism or a feeling of being fundamentally ‘wrong.’

◆ The beauty of imperfection