“It is our choices that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.”

For a long time, this quote by Professor Dumbledore in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series has resonated with me, serving almost as a personal motto. Now, as I delve into the topic of “choices in life,” it seems fitting to begin my reflection with it.

For those who are not familiar with the Harry Potter novel, here is a little background information about the statement (you can Google it if you would like to learn more details; for obvious reasons, I cannot be too lengthy about it here):

Upon arriving at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry, young Harry faced the Sorting Hat – an enchanted hat that determines which of the four Hogwarts houses each student is best suited to. The Hat, after probing Harry’s mind, announced that he would do exceptionally well in Slytherin, a house known for ambition, cunning, and a certain disregard for rules to achieve their ends. Slytherin produced many great wizards, but also, notoriously, dark wizards. The Hat saw Harry’s potential for greatness within Slytherin’s mold.

However, Harry, even as an eleven-year-old, felt an instinctive aversion to Slytherin. He expressed a quiet but firm preference: “Not Slytherin.”

In a crucial turning point, the Sorting Hat acknowledged Harry’s desire. “Are you sure? Well, if you’re sure… better be… GRYFFINDOR!” it declared. Gryffindor is the house of bravery, chivalry, and daring.

This moment is key: the Hat recognized Harry’s abilities might align with Slytherin, but it was Harry’s choice, his conscious desire to be different, that truly defined where he belonged.

Later in the series, Harry’s true Gryffindor nature is confirmed when he is able to pull the Sword of Gryffindor from the Sorting Hat – a feat only a true Gryffindor can achieve. It wasn’t innate ability alone, but the choices he made, aligned with Gryffindor values, that solidified and “earned” his identity.

This story, though fictional, beautifully mirrors a fundamental truth about the power of every decision we make. When I reflect on it, I cannot help but recall Anne Frank’s words:

Our lives are fashioned by our choices. First we make our choices. Then our choices make us.

Life, in essence, is a tapestry woven with choices, large and small, visible and unseen. From the seemingly mundane decisions of each day to the monumental crossroads that dramatically alter our course, we are constantly navigating a landscape shaped by our own making.

Highlights

- Life is a continuous series of choices, both conscious and unconscious, that shape our experiences and define who we are. Every decision, no matter how trivial it may seem, contributes to shaping our character and influencing both our destiny and that of the wider world.

- Even though we make choices in a variety of life domains, all of them, essentially, boil down to a decision between pursuing Growth, which expands potential and fosters connection, or Diminishment, which contracts experience and limits possibilities.

- As straightforward as it may seem, making life choices is not so simple due to the interplay of fate, free will, authenticity, bad faith, uncertainty, and the paradox of choice.

- We all possess the agency to believe that we have a choice in life – that we are free to shape our trajectory or not.

- The key to navigating life’s crossroads is to balance internal agency with external influences – to focus on controllable elements while acknowledging the interconnectedness of everything, and understanding that even within constraints, one still retains the ability to reshape reality by making decisions aligned with the inner compass.

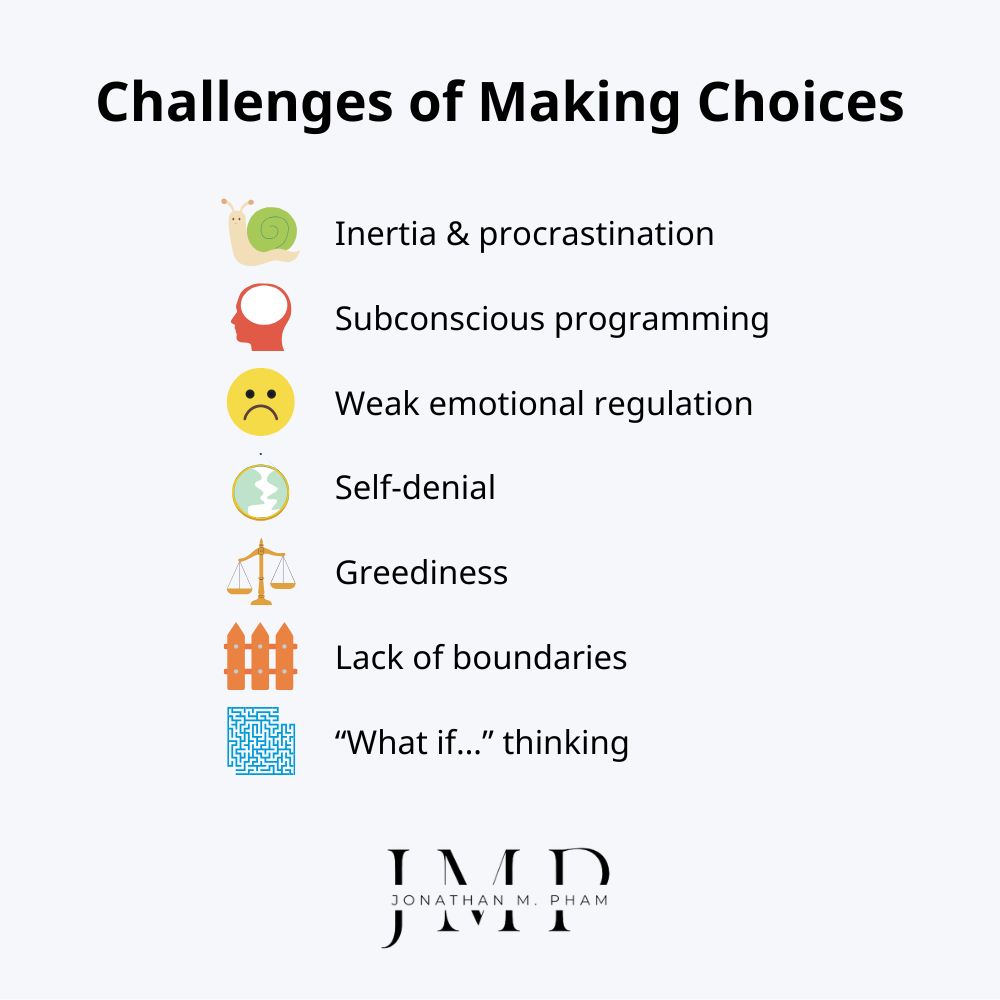

- Often, problems such as inertia, subconscious programming, weak emotional regulation, self-denial, greed, confusion about one’s purpose, and “what if” thinking prevent us from coming up with good decisions.

- The choices we make carry significant responsibility, as they ripple outwards, affecting not only ourselves but also those around us and the world at large. Hence, we need to consider them mindfully and be willing to accept unforeseen consequences.

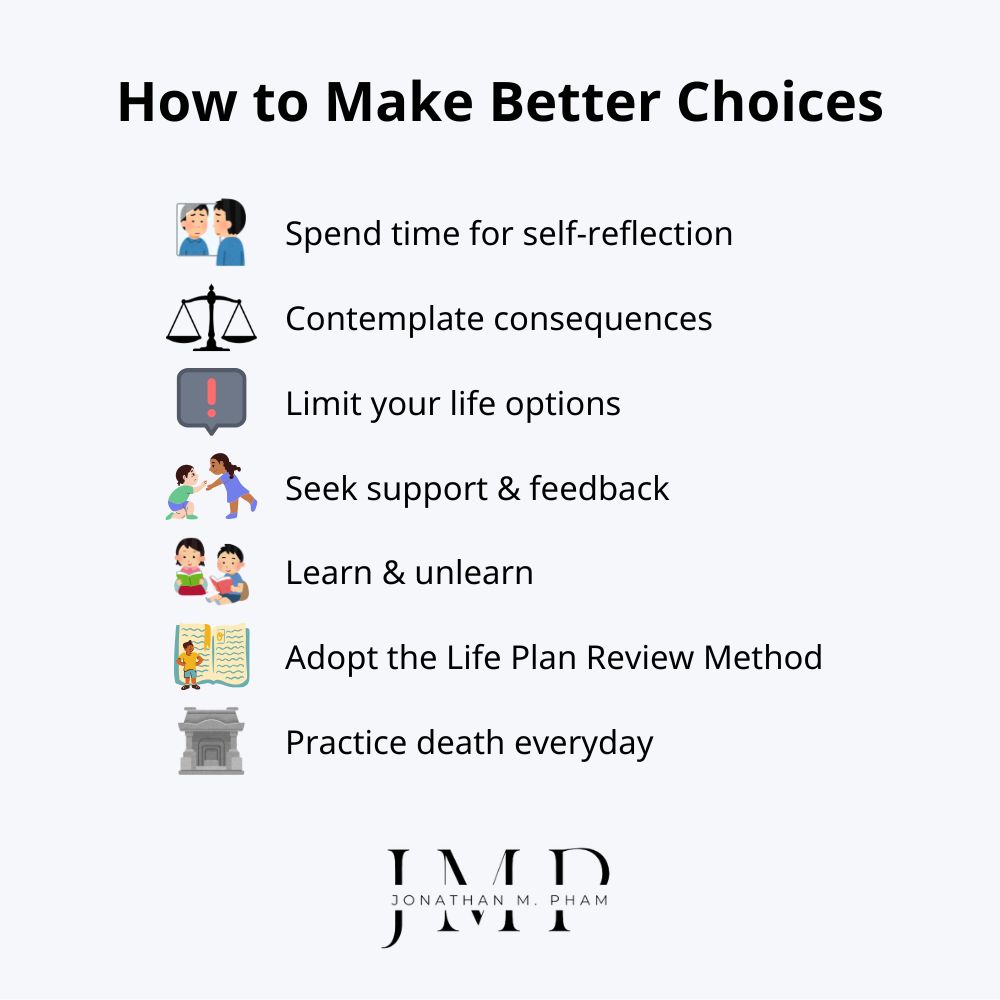

- To come up with better choices that we are less likely to regret, we should spend time practicing self-reflection, considering the consequences of our doings, limiting options, seeking support from others, embracing continuous learning, utilizing planning methods, and, if possible, contemplating our own demise every day.

- Regret is a universal human experience arising from choices made and paths not taken; however, it can be overcome by accepting what has happened, focusing on the present, recognizing the constant potential for positive change, and choosing one’s attitude.

- When it comes to making choices – especially the more difficult ones and those that have the potential to impact others, one should favor those that expand and enrich others while humbling oneself, prioritize ethical and human implications over self-interest, recognize the inherent goodness of humanity, and, above all, maintains an unwavering hope for a better future.

Choices in Life Examples

Just think about a typical morning: will it be coffee or tea to awaken the senses? A seemingly trivial preference, yet even such a small act has the potential to set the course for our whole day.

From the moment we awaken until we drift back to sleep, we are immersed in a sea of possibilities, constantly navigating through branching paths.

As we journey through life, the choices we have to make become increasingly significant.

- We stand at forks in the road, contemplating university degrees that could determine our intellectual pursuits and career paths that will define our professional courses.

- We navigate the intricate landscapes of relationships – choosing partners, cultivating friendships, nurturing family bonds – decisions that profoundly impact our emotional well-being and sense of belonging.

Beyond these major life events, we are also perpetually faced with choices that sculpt our inner selves.

- What ethical compass will guide my actions?

- Will I prioritize core values like honesty, compassion, or justice?

- What beliefs will form the bedrock of my worldview?

- Will I lean towards a life of simplicity or abundance, of introspection or outward engagement?

- Will I consciously cultivate kindness over self-righteousness, understanding over judgment?

- What faith, if any, will provide solace and meaning to me?

- etc.

In every life domain, we are constantly deciding what to embrace, what to reject, and where to stand. And many times, our choices are made without us being consciously aware of it.

Have you ever woken up on a rainy day? Unbidden, gloom begins to settle in. Some days, we – intentionally or not – succumb to the impact of the weather and let it dictate our inner state. And other days, we observe the rain with an inner sense of warmth and gratitude.

These seemingly automatic reactions are, at their root, choices too. Choices we can learn to recognize and, ultimately, consciously direct.

The Importance of Making Choices in Life

Life is the sum of all our choices.

Albert Camus

Have you ever been in a situation like this? You are traveling when you arrive at a crossroad, where multiple paths diverge.

You choose one – only to find it leads to a dead end. Or, to end up in heavy traffic. Navigating out of it, retracing your steps, and getting back on course is a truly arduous experience – physically and mentally.

This simple metaphor reflects the very real impact of our life choices. The paths we select determine where we end up, how smoothly we travel, and indeed, whether we reach the desired destination at all.

Choices in life

Over the years, experts across various fields, from psychology to leadership, have agreed on one crucial point: the ability to make decisions is a fundamental life competency. It is the engine that drives personal growth and shapes the very trajectory of one’s existence.

Our choices are the architects of our character. Do we choose courage over comfort, integrity over expediency, compassion over indifference? These repeated selections, both large and small, etch the lines of our moral compass and define the person we become.

In turn, character forges destiny. The aggregate of our daily decisions determines the opportunities we attract, the relationships we cultivate, and the legacy we leave behind.

What’s more, the choices we make produce a rippling effect, influencing not only us – but also those around us, and even, in a cumulative sense, the world at large.

Let us reflect on an example – about pursuing higher education. Choosing a particular university is not just about acquiring knowledge or securing a career path. It’s a decision that immerses you in a specific environment – connecting you with certain friends, teachers, and professional networks. These relationships, in turn, are potent forces that shape your personality, outlook on life, and future opportunities in ways you might not even foresee.

Imagine choosing a highly competitive school driven by prestige alone. While it might ignite a competitive spirit within you, this drive potentially comes at a cost. Specifically, it might push you to prioritize external validation over inner well-being, leading to a life imbalanced, perhaps sacrificing genuine connections for the sake of fleeting accomplishments, driven by a “reputation-craving self.” (mind you, this was what happened to me before)

Every choice, therefore, reverberates outwards, touching lives and shaping the collective landscape.

Choices in life meme

When we internalize the sheer impact of choices, we are invited to move from passive recipients of fate to active architects of our own becoming.

When we embrace such a responsibility, we minimize the grounds for regret and maximize the potential for authentic choices that pave the way for a deeply fulfilling life.

Life is a matter of choices, and every choice you make, makes you.

John C. Maxwell

Why are choices important in life?

Read more: Choosing Your Life – From ‘Drifting’ to ‘Defining’

Types of Choices in Life

To be, or not to be – that is the question.

William Shakespeare

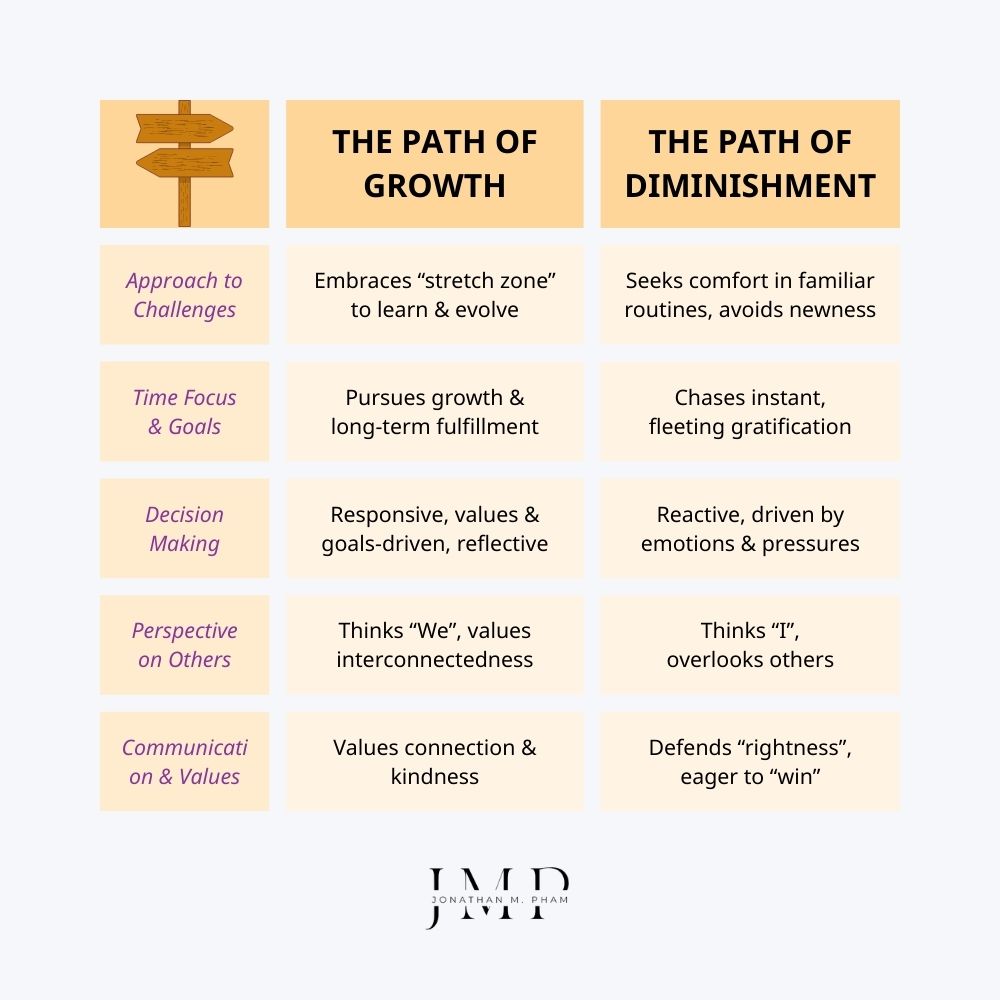

As mentioned above, there are countless areas in life where we make decisions – career, partner, home, and so on. However, I believe they all boil down to a choice between two primary paths: Growth or Diminishment.

Do we consistently choose actions, thoughts, and perspectives that expand our potential, enrich our experience, and contribute to something larger than ourselves?

Or do we, through neglect, fear, or short-sightedness, unknowingly take paths that lead to contraction, stagnation, and ultimately, a lesser version of ourselves and the world?

The path of growth

The path of growth represents an active and intentional stance toward life. It’s about embracing expansion, potential, and a continuous unfolding of who you can become, both individually and collectively.

Key elements:

- Embracing the stretch zone – which can be intellectual (tackling a challenging book), emotional (engaging in a vulnerable conversation), or practical (taking on a new project) – so as to learn, adapt, and evolve as individuals.

- Pursuing long-term fulfillment rather than short-term gratification – by investing time in skill development instead of instant entertainment, nurturing relationships instead of fleeting pleasures, or pursuing meaningful work over solely chasing quick financial gains, etc.

- Pausing, reflecting, and consciously choosing actions based on one’s values and goals (responsiveness), rather than being swept away by circumstances (reactiveness).

- Considering the impact of one’s choices on others (family, community, the world, etc.), and shifting from a purely “I” centric perspective to acknowledging the interconnected “We”.

- Being vulnerable and willing to extend kindness, compassion, and love unconditionally – both to oneself and others – without caring too much about being “right” all the time.

The path of diminishment

In stark contrast, the path of diminishment is often a more subtle and insidious journey. It’s rarely a conscious declaration, but rather a gradual drifting – a series of small concessions that, over time, constrict our “world” and shrink our potential.

Key elements:

- Seeking refuge in the same routines, year after year – even when they lead nowhere new. It’s the intellectual comfort of endlessly scrolling through social media (rather than reading), or the emotional comfort of engaging in superficial small talks.

- Chasing fleeting gratification – the instant validation of social media likes, the short-lived pleasure of impulse buys, the momentary escape of endless entertainment, etc.

- Operating reactively, like a “candle in the wind”, and letting all decisions become dictated by emotions, external pressures, and immediate demands, without pausing to reflect or align with one’s values (e.g. snapping at a loved one in anger in response to a minor inconvenience).

- Living in an “I”-solated world, building walls instead of bridges, seeing the world primarily through the lens of personal needs/ desires, and overlooking the interconnectedness of life (e.g. consistently prioritizing one’s own individual goals at work, even when it means not supporting team members or contributing to a collaborative environment).

- Defending “rightness” at the expense of connection, and being too eager to “win” arguments instead of trying to learn from other perspectives.

| Feature | Path of Growth | Path of Diminishment |

| Approach to Challenges | Embraces “stretch zone” to learn and evolve | Seeks comfort in familiar routines, avoids newness |

| Time Focus & Goals | Pursues long-term fulfillment, invests in growth | Chases fleeting gratification, instant pleasure |

| Decision Making | Responsive, values & goals-driven, reflective | Reactive, driven by emotions & external pressures |

| Perspective on Others | Considers impact on “We”, interconnectedness | “I”-centric, overlooks interconnectedness, isolated |

| Communication & Values | Values connection & kindness over being “right” | Defends “rightness” over connection, eager to “win” |

Each of us has two distinct choices to make about what we will do with our lives. The first choice we can make is to be less than we have the capacity to be. To earn less. To have less. To read less and think less. To try less and discipline ourselves less. These are the choices that lead to an empty life. These are the choices that, once made, lead to a life of constant apprehension instead of a life of wondrous anticipation.

And the second choice? To do it all! To become all that we can possibly be. To read every book that we possibly can. To earn as much as we possibly can. To give and share as much as we possibly can. To strive and produce and accomplish as much as we possibly can.

Jim Rohn

The Complexities of Making Life Choices

Nothing is more difficult, and therefore more precious, than to be able to decide.

Napoleon Bonaparte

The act of deciding, especially when faced with significant life choices, is far from simple. It is a process fraught with intricacies, demanding careful consideration and often wrestling with profound uncertainties.

Far too often, we are not simply presented with clear-cut options and obvious best routes. Instead, we navigate a landscape complicated by a multitude of interwoven factors (which we are going to discuss below).

Questioning life choices

Fate vs. free will

Determinism

The notion of fate suggests that humanity is governed by forces beyond individual control. From ancient Greek tragedies where characters were ensnared in inescapable destinies to certain religious and spiritual traditions that posit either a divine plan or karmic law, the idea that one’s paths are pre-written has a long and enduring history.

In a more modern, secular guise, determinism finds resonance in scientific perspectives, such as Sigmund Freud’s emphasis on cause and effect in the human psyche. It proposes that every event, including the decisions we make, is causally necessitated by prior events.

If every action is a predictable consequence of what came before, where does that leave room for genuine choice?

Is our sense of choosing merely an illusion, a narrative we construct after the fact to rationalize events already set in motion?

Libertarianism

In stark contrast stands libertarianism, championing the power of free will. This perspective asserts that we are, at least to some significant degree, the authors of our own actions. We possess genuine autonomy, a capacity for self-determination that transcends mere causal chains.

Libertarianism highlights humanity’s subjective experience of freedom – the feeling of deliberation, of weighing options, of consciously selecting one path over another. It places a strong emphasis on one’s moral responsibility; if our choices were not truly ours, how could we be held accountable for them?

Compatibilism

And then we have compatibilism, a nuanced perspective that seeks to reconcile the two above-mentioned poles. It acknowledges the myriad of influences shaping one’s existence – genetics, upbringing, environment, societal pressures, chance encounters. In other words, we are not entirely unbound agents operating in a vacuum. That being said, within the constraints of these influences, we still possess a degree of agency, a space for conscious deliberation and choice.

Even if the choices we make are not entirely uncaused – even if they are shaped by our predispositions and circumstances – they are still our choices, reflecting our values, desires, and intentions.

The critical point in compatibilism is not whether one’s will is absolutely free from any cause, but whether one experiences and exercises freedom within their determined existence.

Choices in life

For my part, I believe that I lean more toward compatibilism – a “middle ground” that strays away from extremes and focuses more on practicality.

Consider, for example, choosing a career path. Are your inclinations towards a certain field simply a result of your genetic predispositions and environmental conditioning (deterministic view)? Or are you genuinely free to choose any path, regardless of circumstances (libertarian view)?

Or perhaps, as compatibilism suggests, your background and tendencies MAY play a role in shaping your inclinations, but you still possess the agency to critically evaluate these influences and consciously choose a path that resonates with your authentic self, even if it means defying certain predispositions.

Think about it.

In our daily routine, we practically experience and operate as if we possess free will. We deliberate, we weigh options, we feel the weight of responsibility for our decisions, and we hold others accountable for theirs.

We can certainly act according to our will – we can choose to pursue a certain career, end a relationship, or embrace a new belief. But what determines our will itself?

What shapes our desires, our values, and our deepest inclinations?

Are even our desires freely chosen, or are they themselves products of forces beyond our conscious control?

Man can do what he wills, but he cannot will what he wills.

Arthur Schopenhauer

After all, regardless of one’s philosophical stance, the practical imperative remains: we must make choices, and we must navigate life AS IF our decisions matter.

It is within this space of perceived freedom, however constrained or influenced, that we construct our lives and define who we become.

Authenticity

The concept of authenticity, commonly associated with existentialism, essentially points to living in accordance with one’s true self.

For many, the journey toward authenticity begins with self-knowledge. This involves a deep and ongoing exploration of one’s values, deepest desires, inherent capabilities, and genuine interests. It’s about realizing what truly matters to them, what ignites their passion, and what aligns with their inner compass, independent of external validation.

When we make choices that resonate with this self-understanding, we are, in theory, moving closer to authenticity.

However, the thing is, we live in a world awash in external influences – from the subtle yet pervasive messages of advertising that shape our desires to the curated realities presented on social media that mold our perceptions of success and happiness. Cultural norms and societal expectations further complicate the picture, often dictating what constitutes a “good” or “worthy” life, potentially leading us to pursue paths that may not feel genuine at all.

Far too often, the constant barrage of these external noises drowns out the quieter whispers of our own inner voice, making it incredibly challenging to discern our “true self”.

At the same time, the very notion of a fixed, essential “true self” is itself debatable. Some philosophical perspectives argue against the idea of a static, unchanging core identity waiting to be discovered. Instead, they propose that the “self” is fluid, constantly evolving, and shaped by our experiences and decisions.

From this viewpoint, authenticity is less a destination and more an ongoing process. It’s not about uncovering a pre-existing “true self,” but rather about actively creating a self through conscious and deliberate choices.

We are what we think. All that we are arises with our thoughts. With our thoughts we make the world.

Buddha

While the pursuit of authenticity is generally seen as a positive endeavor, it’s also crucial to acknowledge its potential pitfalls – how it may veer into selfishness if not handled with care.

If we become solely focused on “being true to ourselves” without considering the impact of our choices on others, we risk becoming self-absorbed and inconsiderate – thereby damaging our relationships with others.

If we rigidly cling to a fixed idea of who we should be, we close ourselves off to new perspectives and opportunities for growth.

Bad faith

A concept articulated by existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, “bad faith” is typically seen as the opposite of authenticity. It refers to a form of self-deception, a strategy one employs to evade the anguish of their own freedom and the burden of absolute responsibility that comes with it.

At its core, it is about avoiding responsibility for one’s choices. Instead of acknowledging ourselves as the authors of our decisions, we pass the buck and attribute them to external forces (e.g. fate, destiny), to pre-determined roles (e.g. “It’s just part of my job”), or to unavoidable circumstances (e.g. “I know it’s not good, but my boss told me to do so”).

We engage in a kind of internal playacting, convincing ourselves that we had no choice – that our actions were dictated by something outside of our own volition.

Another significant manifestation of bad faith lies in blindly following societal norms or expectations WITHOUT personal reflection. Specifically, we might adopt career paths, relationship models, or lifestyles simply because they are deemed “normal,” “respectable,” or “expected” by our family, culture, or society.

In bad faith, we convince ourselves that we are simply fulfilling our designated roles – “being a good son/daughter,” “being a responsible professional,” “being a conforming member of society.”

We relinquish our individual judgment and critical thinking, embracing pre-defined scripts rather than actively authoring our own lives.

No doubt I do act in ‘bad faith’ when I deliberately avoid facing an honest decision and follow the conventional pattern of behavior in order to be spared the anxiety that comes when one is… thrown into seventy thousand fathoms.

John Macquarrie

The allure of bad faith is understandable, as it offers a kind of comfort in conformity. After all, the responsibility of choosing, of potentially making mistakes, of bearing the full weight of our decisions – this may be daunting for many of us. Bad faith provides an escape route, an illusion that alleviates this existential anxiety.

However, such comfort comes at a cost – at least in certain situations. Our choices, made in bad faith, may lead to careers that are soul-crushing despite external success, or relationships that are hollow despite fulfilling societal expectations.

These are decisions made to appease others or to conform to external pressures, rather than those that resonate with one’s own core.

Uncertainty

Early in my career, I found myself in a workplace that, in many ways, was ideal. The environment was supportive, the team collaborative, the company culture genuinely positive, and even the compensation was adequate. In many respects, all of my subsequent roles have paled in comparison to this one.

Yet, the work itself was… static. It offered little opportunity for skill development or intellectual growth (you can learn more about my experiences with it here).

After two years, a dilemma arose: should I remain in this comfortable harbor, content with the pleasant surroundings but intellectually stagnant? Or should I venture out into the uncertain seas, seeking challenges that would stretch my abilities, even if it meant leaving behind the known comforts?

I believe that most of us have been through situations like this before. Every decision, no matter how well-thought it is, essentially requires us to make a leap of faith into ambiguity – which is, most of the time, not comfortable at all.

Human beings have a natural inclination to fear the unfamiliar. Our minds are wired to seek patterns, predictability, and control. Uncertainty, by its very definition, disrupts this desire for order. It evokes anxiety – because it threatens our sense of security and the ability to foresee/ manage the consequences of our actions.

When faced with important life choices – career changes, relationship commitments, geographical moves – we are confronted with a daunting array of unknowns. Will this new path lead to fulfillment or disappointment? Will this relationship bring joy or heartache? Will this change enhance my life or destabilize it?

These questions cause many to become mentally paralyzed, making the act of choosing feel like navigating a maze in the dark. As a result, many CHOOSE to cling to the status quo, even if it is unsatisfying or even subtly painful.

We may DECIDE to remain in a state of quiet desperation due to a deep-seated fear of potentially making the “wrong” choice and facing unforeseen negative consequences. The discomfort of staying put, while real, is still perceived as less daunting than the potentially sharper, but unknown, pain of venturing into the uncertain.

The paradox of choices

This concept, popularized by psychologist Barry Schwartz, challenges the seemingly straightforward notion that more is always better. It reveals a surprising truth: an abundance of choices can, paradoxically, lead to decreased satisfaction, increased anxiety, and even paralysis in decision-making.

The modern world, particularly in developed societies, is characterized by an unprecedented proliferation of options. From the mundane choices of which coffee to order or which streaming service to subscribe to, to the significant decisions of career paths, relationships, and lifestyles, we are bombarded with possibilities at every turn. This explosion of options is typically lauded by social media as a triumph of freedom and progress.

And yet, instead of feeling empowered, many of us find ourselves feeling burdened, stressed, and ultimately less happy with our choices.

We succumb to a phenomenon called decision fatigue. The sheer cognitive efforts required to evaluate and compare a vast array of options deplete our mental resources. By the time we actually come up with a decision, particularly for less consequential matters, we may find ourselves mentally exhausted, less satisfied with our eventual choice, and less motivated to engage in further decision-making.

This fatigue can spill over into more important life domains, leading to rushed, impulsive decisions, or even complete analysis paralysis – the inability to make up one’s mind.

With fewer options, our expectations are naturally lower, and we are more likely to appreciate the paths we take. However, when faced with a plethora of alternatives, our expectations, naturally, become inflated. We begin to imagine the “perfect” choice, the one that maximizes every possible benefit.

When we finally do choose, we are often plagued by “what if” thinking. Did we make the best possible choice? Could we have been happier with another option?

This constant comparison and counterfactual thinking diminishes our satisfaction with even good choices and fuels post-decision regret.

Do I Have a Choice or Not?

I’ve told you two stories about what happened out on the ocean. Neither explains what caused the sinking of the ship, and no one can prove which story is true and which is not. In both stories, the ship sinks, my family dies, and I suffer. So which story do you prefer?

Piscine Molitor Patel – “Life of Pi”

As we’ve journeyed through these various layers of complexity – the enduring tension between fate and free will, the elusive pursuit of authenticity, the subtle trap of bad faith, the daunting presence of uncertainty, and the paradoxical burden of overwhelming choice – it becomes undeniably clear that making meaningful life decisions is far from a simple, linear process. Given all these forces at play, do we truly have a choice at all?

I myself believe that the answer itself is a matter of perspective, a choice IN ITSELF. Specifically, we can CHOOSE to believe we are mere puppets of destiny, or we can CHOOSE to believe in our capacity to shape our own paths, even amidst the currents of external forces.

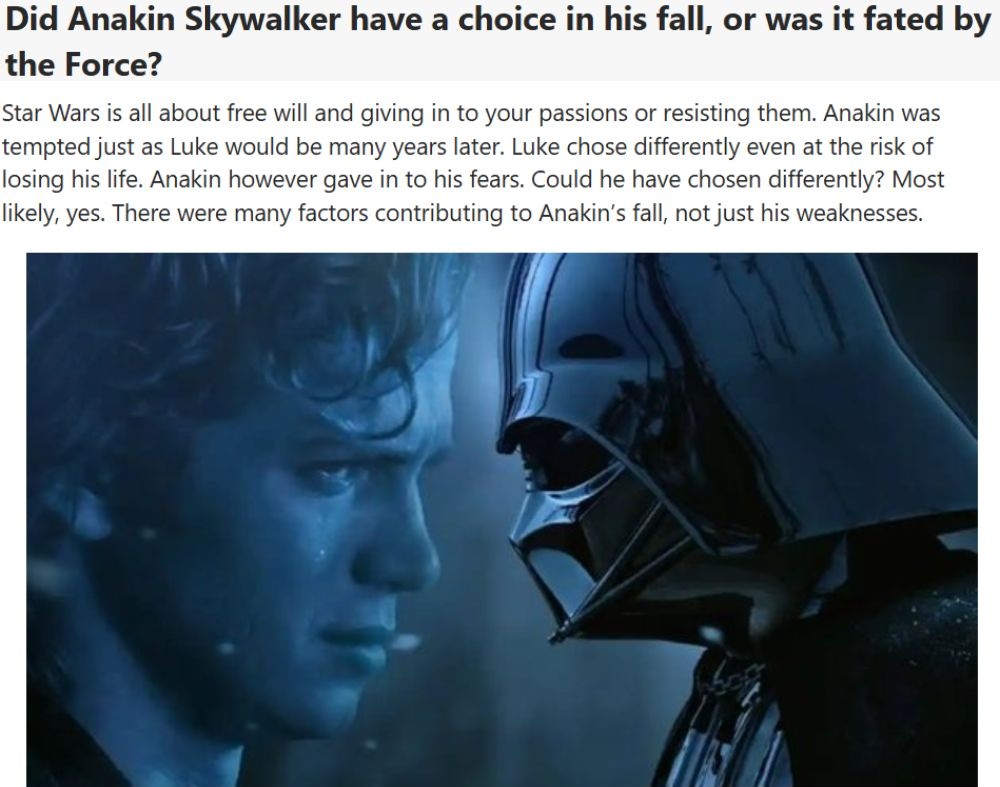

To illustrate this complexity, let us turn to a powerful narrative from popular culture: the saga of Anakin Skywalker in Star Wars.

For those unfamiliar, Star Wars is a sprawling epic set in a galaxy far, far away, where a mystical energy field known as “The Force” connects all living things. Anakin Skywalker is introduced as a young boy believed to be “The Chosen One,” prophesied to bring balance to the Force. Endowed with extraordinary abilities and potential, he is brought into the Jedi Order, an ancient order of peacekeepers who wield the light side of the Force.

However, despite his immense promise, Anakin’s journey takes a tragic turn. Plagued by visions of loss and driven by fear of losing loved ones, he is manipulated by a sinister figure, Emperor Palpatine, and ultimately succumbs to the dark side of the Force, becoming the infamous Darth Vader – a figure of tyranny and destruction.

Anakin’s story is rife with the tension between fate and free will. His initial designation as “The Chosen One” suggests a predetermined path, a destiny seemingly laid out by the Force itself. His visions of future suffering further reinforce this sense of inevitability.

And yet, his journey is also punctuated by countless moments of choice. He chooses to act on his fears, to distrust the Jedi Order, and ultimately, to embrace the dark side.

To what extent were these decisions truly free? Was Anakin merely fulfilling a tragic prophecy, or did he actively author his own downfall? This is the very crux of the debate.

Recently, while exploring discussions on this topic, I happened to come across a Quora post, in which I found some pretty interesting analyses:

Analysis by Milan Miloradovic

Analysis by Dan B

As the two fans above argue, while Anakin’s path to Darth Vader might have seemed “likely” given his circumstances and weaknesses, it was not necessarily predetermined. There were external factors that contributed to his downfall – the flaws of the Jedi Order, Palpatine’s manipulation, the failings of his mentors – but ultimately it was Anakin himself who chose to join the dark side. To commit evil acts, particularly the horrific act of killing children.

Anakin Skywalker’s saga, as tragic as it is, serves as a powerful mirror reflecting our own internal struggles with choice.

Returning to the fundamental question: “Do I have a choice or not?”, again, I would like to assert that the very act of answering is, in itself, a decision to be made.

We can choose to see ourselves as puppets on strings, predetermined by fate or circumstance, or we can choose to embrace the belief in our own agency, our capacity to shape our paths even within the currents of influence. Indeed, the choice to answer “yes” or “no” to this very question is, ultimately, ours.

Just as in ‘Life of Pi’ we are presented with two different stories and asked which we prefer to believe, so too with the question of choice – we can choose the story we tell ourselves about our own agency.

We can choose to believe – or disbelieve – in our own power to choose.

And for me, the empowering path lies in choosing to believe in one’s agency. To look INWARD rather than OUTWARD.

Making Choices in Life: A Balance Between What is “In Here” and What is “Out There”

In traditions like Buddhism, there is a concept called “dependent origination“, which, in its essence, speaks to the interconnectedness of all things. Accordingly, while each being possesses individual will and agency, our existence is fundamentally interwoven and interdependent.

We are individual actors, yes, but we operate within a vast web of interconnected causes and conditions. As such, we need to realize (and aim for) a delicate balance between individuality and collectivity, between personal agency and the larger forces that shape our reality.

No man is an island.

John Donne

Many times, life throws us detours, unexpected incidents that seem to veer us off course, guided by these larger, interconnected forces. However, these detours do not negate our agency.

Even when forced to take a different route than initially envisioned, the underlying direction, the core values and aspirations guiding us, can remain constant.

The path may twist and turn, becoming vastly different from what we initially expected, but the compass setting – our inner direction – can still hold true.

To me, it is, in many ways, just a matter of perception. Often, due to ignorance and a lack of self-awareness, we may not fully grasp the forces at play, nor understand our own inner compass clearly. As such, we may misinterpret detours as failures, or external influences as absolute dictates.

However, with deeper self-knowledge, we can learn to see events with greater clarity, to accept reality as it is – a complex interplay of agency and influence – and ultimately, to transcend the binary of fate versus free will altogether.

It’s about finding agency within influence, freedom within constraints. About focusing energy on what lies within our sphere of control, while leaving the rest – the external influences, the “dependent origination,” the currents of “fate” – to unfold as they may.

This, I believe, is not passive resignation, but rather a strategic allocation of one’s mental and emotional resources. In doing so, we channel our agency into the realm where it is most effective: our own thoughts, actions, and responses. Or, as Stoic philosophers have put it, to “practice dichotomy of control“. To focus on one’s intentions, efforts, and responses to events, rather than fixating on outcomes or external circumstances.

If we can follow this principle, then it will become much simpler for us to make authentic choices that align with the inner compass – and not succumb to external voices.

Just think about historical figures like Gautama Buddha, who renounced a life of princely wealth and comfort to embark on a spiritual quest for truth. Born into a world of immense privilege, seemingly destined for a life of royal succession and earthly pleasures, Siddhartha Gautama, as he was then known, was presented with a pre-ordained path – a ‘fate’ carved out by his birth and societal expectations.

Yet, despite this seemingly gilded cage of circumstance, an ‘inner’ compass stirred within him. Encounters with suffering – the stark realities of old age, sickness, and death – ignited his inherent yearning for wisdom and liberation. Eventually, he chose to see beyond the confines of his immediate, comfortable reality – despite protests and pleas from his family.

His renunciation was a deeply agency-driven decision. And in doing so, the prince, seemingly bound by destiny, transcended the limitations of his birth, becoming the Buddha, the awakened one.

To round it out, let us consider this example. Imagine you are doing a workout. When fatigue sets in, the body – the “out there” – sends signals of weariness, suggesting you stop. These are very real physical limits.

However, within you – “in here” – lies the agency to choose. You can heed the immediate call to stop, or you can push a little further.

What’s interesting is, by consistently choosing to challenge your perceived limits (in a healthy way), day by day, you gradually expand them. The external forces, those initial physical boundaries, begin to shift and no longer confine you as they once did.

This simple example beautifully illustrates the dynamic interplay: your “in here” (your will, your choice to persevere) directly impacts your “out there” (your physical capabilities, your expanded limits).

When we consistently exercise our agency – and align every choice with our inner compass, we create a positive feedback loop. Small acts of agency, like pushing through fatigue in a workout, or deciding to stick to our values in the face of external pressures, compound over time. They strengthen our “inner” capacity and subtly reshape our “outer” reality.

Once you make a decision, the universe conspires to make it happen.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Challenges of Making Choices in Life

Inertia

Inertia is an active event in which we are persisting in the state we’re already in rather than switching to something else.

Marshall Goldsmith

When it comes to making authentic life choices, inertia represents a significant challenge. It is the invisible force that keeps us tethered to the familiar, even when our inner compass yearns for a different direction. Think of it as the force that makes it so much easier to stay on the couch watching television than to embark on that challenging but rewarding new project.

Inertia is the reason we often stick with unfulfilling routines, relationships, or even career paths, simply because the act of changing feels too daunting.

Where does inertia come from? There are several interwoven factors that contribute to its often-powerful grip:

- Fear of change

At its root, inertia arises from a deep-seated fear of the unknown and the potential discomfort of change. This fear is particularly pronounced for individuals who have experienced negative outcomes from past decisions (e.g. someone who made a past career change that ended badly), or those who were raised in overly protective environments that discouraged risk-taking.

Inertia is also fueled by a desire for stability and predictability, a clinging to the perceived safety of the known. In extreme cases, it may manifest as a desire to control one’s environment by remaining static, even in self-defeating ways.

Have you ever heard about a phenomenon called “hikikomori”, when someone exhibits behavior of extreme social withdrawal? While complex, some experts have argued that in some cases, inertia MAY play a role; specifically, the individual may stubbornly remain indoors, seemingly gaining a sense of power or perhaps even pity from others by refusing to engage with the world, rather than facing the uncertainty and challenges of “normal” life.

YOUTH: I have a friend who has shut himself in his room for several years. He wishes he could go out, and even thinks he’d like to have a job, if possible. So, he wants to change the way he is. Except that he’s afraid to leave his room. He wants to change, but he can’t.

PHILOSOPHER: What do you think the reason is that he can’t go out?

YOUTH: I’m not really sure. It could be because of his relationship with his parents, or because he was bullied at school or work. I just don’t know, and I can’t pry into his past or his family situation.

PHILOSOPHER: So, you are saying there were incidents in your friend’s past that became the cause of trauma, and as a result he can’t go out anymore?

YOUTH: Of course.

PHILOSOPHER: So, if the here and now of everyone in the world is due to their past incidents, wouldn’t things turn out very strangely? Everyone who has grown up abused by his or her parents would have to suffer the same effects as your friend and become a recluse.

If we focus only on past causes and try to explain things solely through cause and effect, we end up with ‘determinism’. Because our present and our future have already been decided by past occurrences, and are unalterable.

In Adlerian psychology, we do not think about past ‘causes’, but rather about present ‘goals’.

YOUTH: Present goals?

PHILOSOPHER: Your friend is insecure, so he can’t go out. Think about it the other way around. He doesn’t want to go out, so he’s creating a state of anxiety.

YOUTH: Huh?

PHILOSOPHER: Your friend had the goal of not going out beforehand, and he’s been manufacturing a state of anxiety and fear as a means to achieve that goal. In Adlerian psychology, this is called ‘teleology’.

Ichiro Kishimi – “The Courage to be Disliked”

- The habit of procrastination

When we consistently postpone decisions and actions, our accumulated choices will gradually turn into a habitual state. For example, delaying the decision to leave a toxic relationship, repeatedly postponing the start of a needed exercise regimen, or constantly putting off career planning – these acts of procrastination strengthen the grip of inertia, making it progressively harder to initiate change.

Read more: Habits in Personality Development – A Comprehensive Guide

- The illusion of unlimited time

Especially prevalent amongst younger generations, the feeling that “there’s always tomorrow” can paradoxically lead to a paralysis of action in the present. Time is frittered away on trivial pursuits – endless scrolling on social media, binge-watching frivolous content, or engaging in passive entertainment – with the underlying assumption that there will always be ample time to address important life choices “later.”

This deferred life, however, will soon solidify into a pattern of inertia, making it harder to shift to a more intentional and purposeful way of living.

One day you will wake up & there won’t be any more time to do the things you’ve always wanted. Do it now.

Paulo Coelho

- Obligations & excuses

Life is filled with obligations – family responsibilities, social commitments, existing burdens. And far too often, we resort to them as convenient excuses to avoid making challenging choices.

“I can’t change careers now, I have a family to support.”

“I can’t pursue my passion, I have to take care of my aging parents.”

While these commitments are indeed valid, they may also become shields behind which inertia hides, preventing us from honestly assessing our decisions and seeking authentic paths within or around such responsibilities.

However, inertia is not solely a force of stagnation. In fact, it can be harnessed for good.

When we consciously cultivate productive habits and routines, inertia becomes our ally. Think of establishing a consistent morning exercise routine, preparing a healthy breakfast each day, or optimizing your commute. Once these actions become ingrained, inertia works for you, keeping you grounded and consistent in these positive behaviors.

The key, therefore, lies in initiating movement. Overcoming inertia requires a conscious effort to take that crucial first step – to start the exercise, to begin the career research, to initiate the difficult conversation. Once in motion, the principle of inertia will work in our favor.

Like a snowball rolling down a hill, momentum builds. Small, consistent actions, fueled by initial effort, create a positive feedback loop, making it progressively easier to continue moving forward. Inertia, once an obstacle, can become the very force propelling us towards authentic choices and a more fulfilling life.

When we develop productive (rather than destructive) habits or routines – for example, exercising first thing in the morning, eating the same nutritious breakfast, taking the same hyper-efficient route to work each day – inertia is our friend, keeping us grounded and committed and consistent.

Marshall Goldsmith

Subconscious programming

Reflecting on my own experiences, I recall how, early on, my mother envisioned a specific path for me: that of either a doctor or an engineer. In the prevailing societal view at the time, these professions were lauded as paragons of prestige, promising financial security and social recognition.

While I ultimately diverged from this prescribed route, the influence of my mother’s early programming lingered. I found myself making academic and career choices based on criteria that weren’t truly my own – selecting universities based on competitive admission scores, seeking career paths that promised rapid promotions and higher salaries.

The underlying, often unacknowledged, motivation was not genuine passion or deep-seated contentment, but rather a desire to impress others, to “earn” respect and validation through external achievements – echoes of that initial programming subtly shaping my decisions.

This personal anecdote, I believe, touches upon a fundamental aspect of human experience: we are all, to varying degrees, products of subconscious programming – the beliefs, values, patterns of thought, and emotional responses imprinted upon us from a young age, whether by early childhood experiences, parental messages (both explicit and implicit), cultural norms, societal expectations, repeated exposure to certain narratives, etc.

From the moment we are born, we are absorbing messages about ourselves, about the world, and about what is considered valuable, acceptable, and desirable. These “ideas”, repeated and reinforced over time, become deeply embedded in our subconscious, forming a kind of internal operating system that silently guides our perceptions, reactions, and ultimately, our choices.

Most of the time, we are not aware of how our subconscious is at play every day. We may believe we are making rational decisions, carefully weighing our options, when in reality, we are only acting out pre-scripted programs, responding to deeply ingrained patterns of thought and feeling.

This programming plays a major role in shaping our preferences, desires, fears, aspirations, and even the perception of what options are available to us in the first place. It limits our perceived options, steers us towards decisions that align with it, and leads us down paths that, while perhaps externally successful, may ultimately feel hollow or unfulfilling.

Examples:

- Beliefs about self-worth: Programmed beliefs about one’s inherent value (“I’m not good enough,” “I need to prove myself”) may drive choices aimed at seeking external validation rather than internal fulfillment.

- Limiting beliefs about capabilities: Ingrained notions about one’s talents and limitations (“I’m not creative,” “I’m not good with people”) may discourage the pursuit of paths that genuinely resonate but seem “out of reach”.

- Preconceived roles and expectations: Societal or familial programming about gender, career, or relationship roles (“Women should be caregivers,” “Men should be providers,” “Success means climbing the corporate ladder”) is a common cause of choices that conform to these scripts rather than authentic desires.

- Conditioned responses: Subconscious programs around how to react to achievement and setbacks (fear of success, fear of failure, self-sabotage, perfectionism) can significantly impact the ability to make decisions and pursue meaningful goals.

Becoming aware of one’s subconscious programming is the crucial first step in navigating this challenge. We should recognize the ingrained patterns that may be subtly directing our choices, often without our conscious knowledge or consent. Only then can we begin to question these assumptions, evaluate their validity, and actively choose to rewrite the scripts that no longer serve us.

Weak emotional regulation

Let us revisit the tragic saga of Anakin Skywalker – specifically, how it presents a stark illustration of how unchecked emotions can derail even the most promising of destinies.

While his story is complex, a key thread running through Anakin’s downfall is his struggle with emotional regulation. His turn to the dark side wasn’t a sudden event, but a gradual erosion fueled by:

- A consuming fear of loss, amplified by past trauma;

- A simmering distrust of authority, born from perceived betrayal;

- The intoxicating allure of forbidden love, creating internal conflict; and

- An underlying emotional instability, leaving him vulnerable to manipulation.

Reflecting on the story of Anakin, I can see how fear, especially the fear of loss, has the power to distort judgment, and how emotions, when left uncontrolled, make one susceptible to destructive influences and decisions.

Every day, our choices are typically driven by a myriad of fears.

- The fear of failure prevents us from pursuing challenging but potentially rewarding paths. For instance, being afraid of not succeeding in a new venture might keep someone stuck in a dissatisfying job, even when their inner compass points towards entrepreneurship.

- The fear of missing out (FOMO), particularly amplified in our hyper-connected digital age, is a major cause of impulsive decisions. When we are anxious about being “left behind”, we are tempted to accept commitments or purchases that don’t truly align with our priorities, simply to keep pace with perceived social trends.

- Regret aversion also distorts our choices in the present. Driven by the desire to avoid future regret, someone might stay in a comfortable but stagnant situation, even if that stagnation is itself a source of deep-seated unhappiness.

When we consistently fail to pause, reflect, and regulate our emotional responses, our choices often become reactive rather than responsive. As a result, we become susceptible to:

- Impulsive decisions: Overwhelmed by immediate emotions, we might make rash choices without considering long-term consequences. For example, anger in a conflict makes us utter harsh words that damage a valuable relationship; anxiety about finances might trigger a hasty, poorly researched investment decision.

- Avoidance: Anxiety often drives us to avoid situations that trigger discomfort. The fear of vulnerability might lead to intentionally avoiding intimate relationships; while the fear of public speaking might prevent someone from pursuing a job that requires presentations, even if they are passionate about it.

- Manipulation susceptibility: As seen in Anakin’s story, weak emotional regulation makes us vulnerable to external influences – whether it’s manipulative marketing preying on our insecurities, or persuasive individuals exploiting our fears for their own gain.

Read more: Understanding Emotions – Key to Balance & Success in Life

Self-denial

Another formidable obstacle in the path of making authentic life choices is self-denial – the often-unconscious unwillingness to confront uncomfortable truths and deal with their necessary consequences. It’s a subtle form of evasion, a way we shield ourselves from realities we’d rather not face, even when those realities are crucial for our growth and well-being.

In his bestseller “What got you here won’t get you there“, world-class executive coach, Dr. Marshall Goldsmith discusses our self-denial tendency as follows:

I am in my late 50s. At my age, the most important feedback I need is called an annual physical examination. As feedback, it’s literally life-or-death information. I managed to avoid this feedback for seven years. It’s not easy to avoid a doctor’s visit for seven years, but I did it by telling myself, “I will get a physical after I go on my ‘healthy foods’ diet. I will get the exam after I begin my exercise program. I will get that exam after I get in shape.”

Who was I kidding? The doctor? My family? Myself?

Have you ever avoided a physical exam and told yourself the same thing?

How about a trip to the dentist? After putting off the appointment as long as possible, do you orchestrate a frenzy of dental flossing two days before visiting the dentist’s office?

Admittedly, a little bit of the impulse behind this behavior is our need to achieve. We want to score well in the doctor’s or dentist’s ‘test’, so we prepare for it.

However, a much bigger reason for this behavior is our need to hide from the truth – often from what we already know. We know we need to visit a doctor or dentist, but we don’t because we might not want to hear what he has to say. We figure if we don’t seek out bad news about our health or teeth, there can’t be any bad news.

We do the same in our personal life. For example, when I’m working in a large sales organization, I always throw a spot quiz at the sales force.

“Does your company teach you to ask customers for feedback?” A chorus of yeses.

“Does it work? Does it teach you where you need to improve?” Another yes chorus.

Then I focus on the men: “How many times do you do this at home? That is, ask your wife, ‘What can I do to be a better partner?’ ”

No yes chorus. Just silence.

“Do you men believe this stuff?” I ask. Back to the yes chorus. “Of course!” they say in unison.

“Well, I presume your wife is more important to you than your customers, right?” They nod.

“So why don’t you do it at home?”

I can see their collective wheels turning as the truth dawns on them: They’re afraid of the answer. It might hit too close to home. And, worse, then they’d have to do something about it.

We do the same with the truth about our interpersonal flaws. We figure if we don’t ask for critiques of our behavior, then no one has anything critical to say.

This thinking defies logic. It has to stop. You are better off finding out the truth than being in denial.

I have to confess, I myself am no exception to this tendency towards self-denial. I often find myself engaging in a similar kind of pre-emptive “good behavior” before facing external evaluations. For instance, the frantic flossing ritual before a dentist visit – a burst of dental hygiene after months of neglect.

The ugly truth is: I care less about genuine care for my health and more about wanting to “pass the test,” to present a façade of responsibility, to avoid the discomfort of facing my own lack of consistent self-care.

This unwillingness to face uncomfortable truths poses a significant challenge to making authentic life choices. It operates as a subtle form of procrastination, not just delaying action, but delaying awareness itself. It manifests when we:

- Avoid confronting a difficult career decision, a strained relationship, or a health issue by staying busy with less important tasks, or simply distracting ourselves.

- Create elaborate stories to explain away inconsistencies between our actions and our values, or to justify choices that are driven by fear or comfort rather than genuine desire. “I’m staying in this unfulfilling job for the stability,” even when the real reason is fear of change. “I’m not prioritizing my health right now because I’m too busy with work,” even when the real reason is a lack of self-discipline.

- Resist introspection, dismiss constructive criticism, and surround ourselves with people who only offer validation.

- Make decisions based on how we wish things were, rather than how they actually are (e.g. staying in a failing business because of wishful thinking and denial of market realities).

By avoiding honest self-assessment, we remain in a state of illusion, making decisions based on a distorted perception of reality.

Greediness

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood.

And sorry I could not travel both.Robert Frost

Life often presents us with diverging paths, and the very act of choosing one inevitably means forgoing others. Yet, a significant challenge in making authentic life choices stems from our tendency to resist this reality, from a subtle voice that whispers we can – and perhaps should – try to travel all roads, to achieve all goals, to become, impossibly, “perfect.”

This insidious form of greediness is often amplified by the curated realities of social media, which bombard us with images of seemingly flawless lives and endless possibilities. In this environment, it’s easy to succumb to the affliction – or klesha, as it is known in Buddhist philosophy – of wanting more, of feeling perpetually inadequate, of chasing an ever-receding ideal of perfection.

We begin to believe we need to excel in every domain, to embody every desirable attribute, to become the “perfect” version of ourselves, a mirage constantly fueled by external comparisons and idealized online personas.

Dr. Marshall Goldsmith offers a grounding counterpoint to this perfectionistic trap as follows:

You can’t be and don’t have to be all things to all people. If there were a list of 39 successful attributes for the model executive, I would never argue that you have to be the perfect expression of all 39 of them. All you need are a few of them. No matter how many of the 39 attributes you don’t embody, the real question is, how bad is the problem? Is it bad enough that it merits fixing?

If not, don’t worry about it. You’re doing fine.

I take great comfort in the fact that Michael Jordan, to many the best basketball player to ever play the game, was a mediocre baseball player in the minor leagues and, as a golfer, would have a tough time keeping up with at least twenty golfers who live within an 800 yard radius of my home in San Diego.

If Michael Jordan, a preternaturally superb athlete and competitor – in fact, the benchmark for other basketball players – could only excel at one sport, what makes you think you can do better?

It’s crucial to recognize the absurdity of this perfectionistic tendency. Accepting imperfection isn’t an excuse for mediocrity or for making poor choices; it’s just an embrace of reality – an acknowledgment of our finite nature, limited time and energy, and the simple truth that we cannot be all things, do all things, or have all things.

For example, accepting imperfection in career choices doesn’t mean settling for a job you ACTIVELY dislike. Instead, it means realistically prioritizing what truly matters to you in a career – perhaps meaningful work, work-life balance, creative expression, or intellectual challenge – and internalizing the fact that you might not find a role that perfectly fulfills every possible criterion (high salary, ultimate prestige, minimal stress, complete creative freedom, etc.).

Choices in life

Another facet of greediness that hinders authentic choices is our often-insatiable desire for immediate gratification. Given that we now live in an era of instant access and on-demand fulfillment, it’s easy for this conditioning to seep into our approach to life decisions.

For instance, we may embark on a fitness journey expecting rapid transformations, and become discouraged and give up when progress is slow and requires sustained effort.

Or, someone pursuing a dream of becoming a writer might abandon their aspirations after facing initial rejections, unwilling to endure the prolonged process of honing their craft and navigating the inevitable setbacks.

This impatience, this craving for instant rewards, stems from a kind of greediness – a desire to reap the fruits of our choices without fully investing the necessary time, effort, and perseverance.

Lack of boundaries

Recently, an old friend of mine recounted her struggles with a direct report – a talented but deeply cynical individual who consistently clashed with colleagues, convinced that everyone, especially the general manager, was self-serving and held personal animosity towards him. After listening to her account, I suggested to my friend that perhaps it was simply her direct report’s choice; hence, she might need to accept and work around it. However, my friend immediately recoiled at the idea.

“I can’t just let him be like that,” she insisted.

I could not help but reflect on a shared human inclination: the tendency to believe, often unconsciously, that we are the center of our own, and sometimes even others’, universes – that we have a responsibility to intervene, to judge, to meddle in matters that may not actually be ours to control or even influence.

This inflated sense of self-importance, this confusion about the boundaries of our own roles, can significantly cloud our judgment and complicate the decision-making process.

Back in the day, I came across this story shared by pastor Carey Nieuwhof:

Before ministry, I was a lawyer. In first-year law, I remember having a crisis because I couldn’t imagine representing a client I believed might be guilty.

I stayed after class one day to talk to my criminal law professor about it. He assured me of a few things. First, if your client tells you he’s guilty, you can’t ethically enter a non-guilty plea.

That made me feel better.

But then he told me that almost every client says they’re not guilty.

I got nervous again.

“Well, what if you think he’s guilty but he says he’s not … doesn’t that put you in a horrible bind?”

I’ll never forget his answer.

“You’re confusing your role, Carey. You’re not the judge. You’re his lawyer. Your job is – ethically, morally and legally – to give him the best day he can possibly have in court. The judge will decide whether he’s guilty or not.”

I felt like the weight of the world was lifted off my shoulders.

When we are unclear about where our responsibilities begin and end, when we overstep our boundaries or neglect our actual duties in favor of misplaced ones, we inevitably invite judgment – both of ourselves and of others. We judge others for not living up to our expectations, for making choices we wouldn’t make, or for simply being different. And then we judge ourselves harshly for perceived failures, for not meeting unrealistic standards, or for not controlling outcomes that are inherently beyond our control.

At the same time, believing we are responsible for fixing others or controlling situations that are outside our purview, we are likely to become overly involved in others’ lives, offering unsolicited advice, imposing our opinions, and blurring healthy boundaries. We become fixated on controlling external factors while neglecting the internal work of self-discovery (thereby coming up with decisions that we regret later).

“What if…” thinking

A few days ago, I happened to stumble upon this post on Reddit:

The persistent hum of “what if…” thinking is, indeed, one of the most pervasive and subtly corrosive challenges to making peace with one’s life choices. It is a form of mental counterfactualizing where we endlessly replay past decisions and project ourselves into alternate realities, questioning whether we chose the “right” path, whether we missed out on better opportunities, whether our lives could have been different, and perhaps, better.

What if I had taken that different job offer? What if I had stayed in that past relationship? What if I had moved to a different city? What if I had pursued that other passion?

Some may wonder: why is this seemingly innocuous mental exercise – pondering alternatives – such a significant challenge to making authentic life choices?

The answer is, it erodes contentment with the decisions we did make, fuels anxieties about the past and future, and distracts us from fully engaging with the present.

It erodes confidence in our inner compass, making it harder to trust our judgment and commit wholeheartedly to the paths we do choose.

Challenges of making life choices

The Weight of Responsibility in Making Life Choices

Where your treasure is, there your heart will be also.

As a kid, I first came across this quote in the novel Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows. However, I didn’t quite get what it means, partially because of a somewhat ambiguous translation in my local edition, one that likely missed the quote’s true origin and significance (I assume that the translator was not familiar with it at all).

Years later, I discovered that it is a Biblical quote (Matthew 6:21), that it is also featured in other literary works (e.g. Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist). And that there are layers of very deep meaning embedded within it.

For those who are not familiar with the Harry Potter series, this quote is inscribed by Professor Dumbledore on his mother and sister’s grave. Young Dumbledore, brilliant and ambitious, forged a bond with Gellert Grindelwald, a charismatic but ultimately dangerous wizard. Consumed by a shared vision of wizarding dominance, Dumbledore, in his youthful desire for recognition, allowed himself to be swayed by Grindelwald’s ideology.

The choice to align himself with Grindelwald, to prioritize the allure of power and fame, came at a devastating cost to his family. His sister, Ariana, tragically died during a three-way duel involving Albus, his brother Aberforth, and Gellert. After the incident, Grindelwald fled, while the chasm between Albus and Aberforth deepened and became nearly unmendable.

And Dumbledore, for the rest of his life, lived with profound regret over his decision – how his act of prioritizing ambition and power over love and responsibility has cost him everything. It was this regret that drove him to inscribe the quote above onto his mother and sister’s grave – as a reminder of the price of his choices.

I was her favourite – not Albus, he was always up in his bedroom when he was home, reading his books and counting his prizes, keeping up his correspondence with ‘the most notable magical names of the day.’

Abeforth Dumbledore

As you may see from the story of Dumbledore, our choices, especially significant ones, are never made in a vacuum. They ripple outwards, impacting not only ourselves but also the lives of those we cherish and the world around us.

In the immediate rush of decision-making, far too often, we neglect this weight of responsibility. And yet, being aware of it is a crucial facet of navigating life’s complex choices authentically.

Have you ever heard about a phenomenon called “the butterfly effect“? Originating from chaos theory, it speaks about how seemingly small initial conditions are capable of triggering vast and unpredictable consequences in complex systems.

Imagine a butterfly flapping its wings in Brazil, and theoretically, this tiny action could contribute to the formation of a tornado in Texas weeks later.

While perhaps an oversimplification, the core principle resonates deeply with the nature of life choices: our actions, however insignificant they may seem in the moment, can set in motion chains of events that ripple outwards in ways we can scarcely foresee. This is particularly true for life-altering decisions, where the stakes and potential repercussions are significantly magnified.

Perhaps no story exemplifies the idea more profoundly than that of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Often hailed as the “father of the atomic bomb,” Oppenheimer was a brilliant theoretical physicist who led the Manhattan Project during World War II.

Driven by the urgent need to end the war and fearing Nazi Germany’s potential to develop nuclear weapons first, Oppenheimer and his team embarked on a monumental scientific undertaking. They succeeded in creating the atomic bomb, a technological marvel that fundamentally changed the course of history.

However, the immediate aftermath of their success was devastating. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki resulted in unimaginable death and destruction, instantly obliterating cities and leaving lasting scars on generations. Beyond the immediate tragedy, Oppenheimer’s creation ushered in the nuclear age and the chilling reality of the Cold War, a decades-long standoff fueled by the threat of global annihilation.

Oppenheimer, initially driven by a sense of duty and scientific urgency, was deeply unprepared for the sheer magnitude of these consequences. As he witnessed the horrifying power unleashed by his creation, a profound moral dilemma took root. He famously quoted the Bhagavad Gita, lamenting:

Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

Oppenheimer came to realize the immense weight of the responsibility he and his team bore. In the years following the war, he became a vocal advocate for international control of atomic energy and against the further development of even more destructive weapons like the hydrogen bomb. He denounced the bombing of Nagasaki, expressed deep regret for the devastating consequences of the technology he had unleashed, and worked tirelessly to mitigate the very dangers he had helped bring into existence.

From Oppenheimer’s story, we can see how a decision made within the confines of a laboratory has unleashed a chain reaction of global proportions, impacting millions and shaping the geopolitical landscape for decades to come. A very vivid demonstration of the impact of certain life-altering decisions, particularly those made on a grand scale with global implications.

But the butterfly effect and the weight of responsibility are not confined to world-altering historical events. They are at play in our personal lives as well.

For example, let’s say you decide to start a new business. While seemingly a personal endeavor, it creates jobs, impacts families, influences local economies, and potentially introduces new products or services into the world.

Or, think about choosing a life partner. A seemingly personal decision – yet it has profound ripple effects, shaping not only your own future but also that of your partner, your potential children, and your extended families.

Even seemingly trivial choices, like how we treat a colleague, raise a child, or engage in our communities, contribute to a complex web of interconnected consequences.

How then, do we navigate life with this awareness, without becoming paralyzed by fear or overwhelmed by the potential for unforeseen outcomes?

The key, I believe, lies not in avoiding responsibility, but in embracing it consciously and thoughtfully. In other words, we need to be mindful in the process of decision-making – taking the time to consider the potential ripple effects of our choices, both intended and unintended, to the best of our ability.

It’s about acting with consideration for others, acknowledging our interconnectedness, and striving to make choices that contribute to a more positive and responsible community, within our sphere of influence.

And ultimately, it’s about accepting the inherent uncertainty of life. We cannot foresee every consequence, nor can we control every outcome. But we can control our intentions, efforts, and commitment to making choices with integrity.

Just as Dumbledore, burdened by his past, dedicated his life to protecting the wizarding world, and Oppenheimer, grappling with the legacy of the atomic bomb, worked for peace, we too can strive to do the same. To live responsibly, not like an isolated “island”.

Life is about choices. Some we regret, some we’re proud of. Some will haunt us forever. The message: we are what we chose to be.

Graham Brown

“He chose poorly” – Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade

If you are interested in exploring the topic of moral ambiguity, check out a list of the best movies about ethical dilemmas here!

How to Make the Right Choices in Life

Carve out time for self-reflection

Navigating the labyrinth of life choices, as we’ve explored, is fraught with complexities – from internal inertia to external pressures. The first step toward making better decisions, therefore, lies in cultivating a mindful awareness of ourselves, our inner landscape, and the direction we truly wish to travel.

What got you here?

Consider spending time examining your internal landscape – i.e. your values, beliefs, strengths, and weaknesses. Take stock of your current situation, including both the positive foundations and the limiting aspects that have shaped your path. Try to deduce the principles that have been inherently guiding you, as well as any potential subconscious programs/ troublesome habits that might be steering you away from the paths you wish to take.

Now, let’s say you reflect on your career path and realize the following things:

- Core values: “Helping others and making a tangible positive impact on the world are really important to me. I see this thread in my volunteer work and even my hobbies.” (Guiding principle)

- Positive beliefs: “I’ve always believed in my ability to learn new skills and adapt to challenges. This has allowed me to take on different roles and grow.” (Strength-based belief)

- Limiting beliefs: “Deep down, I sometimes believe I don’t deserve significant financial success. This might be why I haven’t aggressively pursued promotions or higher-paying opportunities, even when I was qualified.” (A potential subconscious program – stemming perhaps from childhood messages about wealth)

- Weaknesses/habits: “I tend to avoid conflict and difficult conversations. This has sometimes led to me staying in uncomfortable situations longer than I should, rather than addressing them directly.” (A potentially troublesome habit – conflict avoidance)

What will get you there?

With a solid foundation of self-understanding, we can then turn to the next question: “What do I truly want, and why?” Think about your genuine desires, beyond external expectations or ingrained programming – as well as the underlying motivations, whether they stem from authentic needs or fleeting whims/ external validation seeking.

After that, assess the necessary steps, resources, and commitments required to bridge the gap between your current reality and your desired future. This is not about crafting an elaborate five-year plan, but rather gaining a clearer sense of direction and the realistic effort involved in pursuing it – translating abstract desires into actionable steps.

Let’s continue with the career example above. Having reflected on “what got you here,” now it’s time to consider “what will get you there”:

- “What do I want?” => “I realize I’m no longer fulfilled in my current corporate role. I yearn for work that directly helps people and aligns with my value of making a positive impact.” (A genuine desire beyond current reality)

- “Why do I want it?” => “Because I feel a deep sense of purpose and satisfaction when I’m helping others directly. External validation and high salaries don’t bring me lasting contentment. I want to feel like my work matters in a meaningful way.” (Authentic motivations beyond external markers)

- “What will it realistically take?” => “To transition to a more purpose-driven career, I’ll need to research non-profit organizations, perhaps take some courses in social work or counseling, network with people in those fields, and realistically accept a potential initial salary decrease. It will take time, effort, and a willingness to step outside my comfort zone.” (Translating desire into actionable steps and realistic considerations – acknowledging effort and potential trade-offs)

Ask basic questions

For those new to the practice of self-questioning, starting with ‘basic questions’ is an incredibly powerful move. As executive coach Marshall Goldsmith has pointed out, while grand existential questions like “What is the meaning of life?” are indeed valuable, effective self-reflection for immediate choices often boils down to simpler, more focused inquiries. For example:

- Do I love my partner?

- Who are my stakeholders?

- Is this approach realistically workable?

- Where have I gone astray in similar situations before?

These ‘basic questions’ aren’t simplistic; instead, they are direct, pointed, and demand honest introspection.

While seemingly straightforward, they require a deep and honest assessment of facts, abilities, and intentions, eliciting the “hard-core truth” about our feelings and aspirations.

Now, let’s say you are considering a new job offer in a fast-paced, demanding environment, similar to past roles. You wonder “Should I accept it or not?”

- Initial answer: “This job is exciting and high-profile! I’m ready for a new challenge!”

- Past facts: “In the last two high-pressure jobs, I burned out within 2 years. My health suffered, and my relationships strained.”

- Past abilities (and limitations): “I know I can handle high pressure for short bursts, but I struggle to sustain it long-term without sacrificing my well-being. My strength is in strategic thinking, not constant fire-fighting.”

- Past intentions (vs. actual outcomes): “My intention in the past was career advancement and financial security. But the outcome was chronic stress and dissatisfaction, even with the ‘success’.”

- Eliciting “hard-core truth”: “Deep down, I dread the thought of repeating that burnout cycle. My gut is telling me this ‘exciting challenge’ is just another shiny object distracting me from my real need for sustainable work-life balance. Am I running towards recognition again – away from the lessons of my past?”

This example demonstrates how reflecting on past patterns through a basic question can reveal deep-seated motivations, unmet needs, and potentially self-sabotaging tendencies.