A personal journey into the expression ‘Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays’, including reflective insights on faith, resilience, and humanity’s search for peace and meaning.

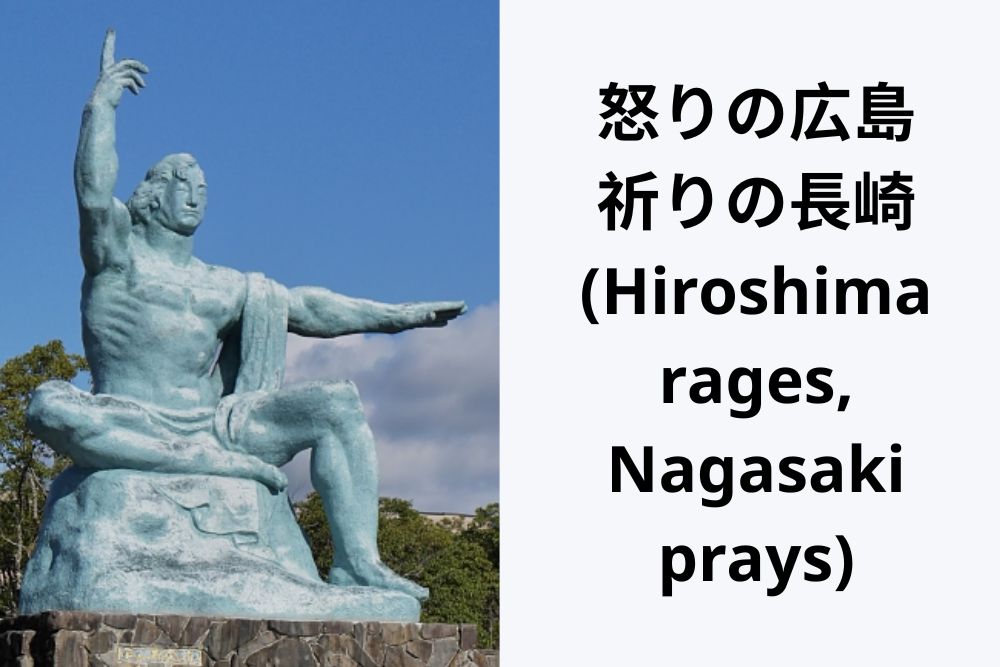

There are phrases in this world that, once heard, embed themselves deep within the mind, stirring the soul with their gravity and the weight of the human history they attempt to encapsulate. For me, one such phrase is “Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays” (怒りの広島、祈りの長崎 – Ikari no Hiroshima, Inori no Nagasaki).

As a non-Japanese (who happens to have a strong interest in things related to Japan), I initially found the thought of wading into the waters of such a sensitive topic so daunting. The sheer scale of the tragedy, the cultural nuances, the intimate pain that still echoes through generations – it all felt like ground that a foreigner, an outsider, should perhaps tread with extreme caution, if at all. There’s a fear, isn’t there, of misunderstanding, of oversimplifying, or of inadvertently causing hurt when discussing wounds so deep.

Yet, the more I thought about it, the more I felt compelled to reflect on it. To try and glimpse, however imperfectly, the human heart beneath the historical narrative.

My sharing below is offered as just that: my own reflection. It’s an attempt, as a foreigner and as a Christian myself, to sit with these stories, to listen to the voices (primarily through a few Japanese sources I’ve encountered), and to see what they might teach me about the human spirit, about the paths we forge through unimaginable darkness, and about the enduring search for peace and meaning.

This isn’t an attempt to provide a definitive explanation of this complex phrase or the histories of these two resilient cities. Instead, I hope to share a personal journey of learning, to explore the layers of meaning that might lie beneath these powerful words – “anger” and “prayer.”

My hope is to approach the topic with the respect and sensitivity it deserves, acknowledging that these are not just historical events, but living memories that continue to shape hearts and lives.

Highlights

- This article embarks on a spiritual reflection of the phrase “Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays,” seeking to understand the complex human experiences and nuanced realities that lie beyond these initial labels.

- Hiroshima’s “anger” is not simply as destructive rage, but a potential sacred fury – a righteous demand for justice, a fierce commitment to ensuring history is never forgotten, and a powerful catalyst for global peace.

- For Nagasaki’s “prayer,” the notion has deep roots in the unique Christian heritage of Urakami, the theological interpretations of suffering like Dr. Nagai’s “Burnt Offering Theory,” and the symbolic choices in memorialization (e.g., the rebuilt Urakami Cathedral).

- One thing worth mentioning about Nagasaki’s “prayer” is its evolution from introspective faith and silent suffering into active vocal witness for peace, as exemplified by survivors whose perspectives were transformed, and a collective aspiration for Nagasaki to be the “last” atomic bomb site – a prayer embodied as a determined vow.

- Ultimately, the aim of this reflective journey is to find the common threads of our shared humanity. Both “anger” and “prayer,” in these contexts, can be profound facets of a universal response to immense loss – a deep love for humanity, a call for empathy, and an enduring commitment to peace.

Unpacking the Narrative: Beyond the Binary

The “image” and its limitations

The expression “Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays” is widely understood as reflecting the distinct attitudes of the citizens in these two cities toward the atomic bombings and their subsequent paths in peace and anti-nuclear movements. It’s a narrative that has taken hold, not just in Japan, it seems, but sometimes even globally.

But human experience, especially in the face of such trauma, rarely fits neatly into concise labels, however evocative they may be.

Grief, pain, memory, and the longing for peace are such deeply personal currents, flowing uniquely through each individual heart. To imagine an entire city feeling only one strand of such a complex emotional tapestry seems an oversimplification – indeed, I’ve read suggestions that such phrases might even be akin to a kind of ‘propaganda’.

Now, the word “propaganda” may feel quite charged, but in a less overt sense, I wonder if it speaks to how collective memories or dominant narratives are sometimes shaped.

Perhaps these labels emerge from a human need to find patterns, to create frameworks out of overwhelming chaos. Or maybe they are amplified because they serve a certain purpose, consciously or unconsciously, in how a story is told and received.

It makes me think: why do we, as human beings, sometimes gravitate towards these simplifying binaries when trying to understand vast, multifaceted experiences?

Is it for clarity? For remembrance? Or do these labels, in their very starkness, sometimes obscure the diverse and personal truths of individual lives and an entire city’s multifaceted soul?

Hiroshima’s “anger”: A sacred fury?

So, if these labels of “anger” and “prayer” are indeed more nuanced than they first appear, what then of Hiroshima’s “anger”?

As I did my own research, I learned of the poet Toge Sankichi, whose collection of atomic bomb poems, Genbaku Shishu, had to be published underground due to censorship at the time. The opening line starts with a raw plea:

「人間を返せ」– Ningen o kaese – “Give us back our humanity.”

There’s no mistaking the emotion there. It is anger. But as I reflect on it, I wonder: is it solely destructive rage? Or could it be something more?

Could Hiroshima’s “anger” be understood as a righteous cry against an ultimate inhumanity? A fierce, protective refusal to allow such an atrocity to be forgotten, downplayed, or repeated?

Not an “anger” that seeks to destroy – but to awaken, to call for change, to protect the vulnerable. One that is directed at profound injustice, at the desecration of human life and dignity.

Not an anger that consumes, but one that fuels a relentless drive for peace, a steadfast demand for “never again.”

A vow to remember and strive for a more humane world.

Atomic Bomb Dome, Hiroshima

(Image credit: Wikimedia)

Nagasaki’s “Prayer”: A Tapestry of Faith, Suffering, and Hope

The shadow of Urakami: Faith and catastrophe

Now, let us turn our attention to the other city. When it comes to Nagasaki, one specific place of interest is Urakami.

As far as I know, it was not only the hypocenter of the second atomic bombing – but also a place with a remarkably rich Christian heritage. For centuries, during times when Christianity was proscribed in Japan, generations of “Hidden Christians” (Kakure Kirishitan) in Urakami secretly kept their faith alive.

Then, on that fateful day, August 9, 1945, it was this very community that bore the brunt of the cataclysm. According to an article published on NHK, of the 12,000 Catholics in the Urakami district, it’s estimated that 8,500 perished in the bombing.

The sheer weight of that reality – a community that had already endured so much for its faith, nearly obliterated in an instant – is almost incomprehensible. And it is within this crucible of suffering that one of the most defining narratives of Nagasaki’s “prayer” emerged, primarily through the figure of Dr. Takashi Nagai.

Dr. Nagai was a Catholic himself, a physician who lost his own wife in the bombing and tirelessly dedicated himself to aiding the victims. In the aftermath, he offered a profound, yet challenging interpretation of the tragedy: the “Urakami Burnt Offering Theory” (浦上燔祭説 – Urakami Hansai Setsu). According to him, the bombing of Urakami, this devout Catholic community, was a form of “God’s providence,” a sacrificial offering, akin to an “Immaculate Lamb,” for the sake of world peace. In a eulogy given three months after the bombing, amidst the ruins of Urakami Cathedral, Dr. Nagai articulated this vision, suggesting that by Urakami’s slaughter, God had accepted humanity’s repentance for the war, leading to its end.

Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays: Nagai Takashi Memorial Museum

(Image credit: Wikimedia)

As a Catholic myself, these words stir something very complex within me. The concept of sacrifice is central to my faith – the ultimate sacrifice of Christ for the redemption of humanity. And throughout history, people of faith have often sought to find divine meaning in the midst of an-fathomable suffering, to see a higher purpose in what feels like senseless horror.

Dr. Nagai’s interpretation, born from his own immense pain and conviction, undoubtedly offered such a framework for many in Urakami, a way to make sense of the unbearable, to consecrate their loss. He is even revered as a “saint” in Nagasaki.

And yet, the idea that God would ordain such suffering, that these lives were a divinely willed “burnt offering,” is one that many, including myself, find so hard to wrestle with.

What then of all the other victims, in Nagasaki and elsewhere, who did not share that specific faith context?

As suggested in a discussion thread, this narrative might also have arisen in a complex social context, possibly as a response to “slander based on Catholic discrimination that ‘atomic bomb = divine punishment’.” If true, framing the victims as holy sacrifices could have been a way for the Urakami community to reclaim dignity in the face of such cruel accusations.

The same discussion also posited, quite critically, that this interpretation might have been more “convenient for the side that dropped the atomic bomb” than a narrative of direct anger.

These are – as I find – heavy considerations. True, they don’t diminish the sincerity of Dr. Nagai’s faith or the comfort his words may have brought to a shattered community. But they DO highlight the immense spiritual and psychological weight that such theological interpretations carry – the search for meaning, the burdens of explanation, and the different paths individuals and communities walk to reconcile faith with catastrophe.

As I reflect on it, I cannot help but think about the mystery of suffering – as well as about the human heart’s persistent, aching need to find a sacred thread, even in the deepest, most bewildering darkness.

The vanished cathedral

Beyond the theological interpretations offered by figures like Dr. Nagai, the very landscape of Nagasaki, particularly Urakami, tells a story of choices that seem to resonate with this overarching theme of “prayer.” At the heart of this is the story of the Urakami Cathedral, once the largest Catholic church in East Asia.

The atomic bomb decimated this sacred place. Yet, unlike Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome, which was preserved in its skeletal state as a monument to the destruction, the ruins of the Urakami Cathedral were eventually cleared, and a new cathedral was rebuilt on the same site. A portion of the original wall was moved to the Peace Memorial Park, a fragment saved, but the primary site chose rebuilding over ruin.

Urakami Cathedral, 7 January 1946

The current rebuilt cathedral

(Image credit: Wikimedia)

This decision itself feels significant. Why rebuild rather than preserve the ruins as another powerful, raw testament to the bombing – especially given that it was a Christian church in a Christian district, bombed by a predominantly Christian nation? (i.e. the US)

The reasons behind this choice – as they seem to me, an outsider – are likely multifaceted and not simple to interpret. However, there are speculations that the possibility of pressure from the United States, for whom such a ruin might have been an “inconvenient” reminder, or complex internal dynamics within Nagasaki itself may have hindered a unified push for preservation. Some perspectives suggest that ruins inherently evoke “negative emotions” and “anger,” and that by removing the physical manifestation of that devastation and embracing Dr. Nagai’s philosophies, “only prayers for peace remain in Nagasaki.”

These are compelling, if sobering, possibilities to consider. They make me reflect on the profound ways communities navigate the aftermath of unspeakable trauma.

Does the act of rebuilding a sacred space signify a primary focus on renewal, on the continuity of faith and community life, rather than on monumentalizing the moment of destruction?

Does it inherently steer the collective memory towards healing and forward-looking prayer, rather than the stark confrontation with “anger” that a ruin might embody?

The enduring bells

Speaking of the theme of “prayer” in Nagasaki, I believe it’s worth mentioning Dr. Nagai’s famous memoir, “The Bells of Nagasaki” – which recounts his firsthand experiences of the atomic bombing’s devastation, the loss of his wife, and the suffering of the city’s residents.

Bells, in my own Catholic tradition and in various cultures worldwide, are richly symbolic. They call to worship, yes, but they also toll in mourning, ring out in celebration, mark the passage of time, and gather a community.

Their sound, unlike a fixed monument, travels, permeates, and can evoke a sense of the transcendent, of an enduring spirit that rises above the rubble.

Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays

(Image credit: Wikimedia)

Perhaps the enduring “bells of Nagasaki”, both literal and metaphorical, represent an ongoing call to prayer, to peace, to a remembrance that is not anchored in the visual horror of destruction alone, but also in the recurring, resonant hope for peace that sound can carry.

It makes me wonder if this choice – the rebuilt cathedral, the emphasis on the message of the bells – speaks to a particular way of holding memory: one where faith, prayer, and the aspiration for peace become the dominant echoes, even as the scars of the past remain indelibly etched on the city’s soul.

From silent suffering to vocal witness: The evolution of “prayer”

The narrative of Nagasaki’s “prayer” might, at first, suggest a quiet, inward-looking piety, a spiritual endurance in the face of unimaginable loss. And while that introspective strength was undoubtedly present, the story doesn’t end there.

The NHK article mentioned above recounts the story of Ms. Tsuyo Kataoka, a Catholic survivor from Urakami. Having lost thirteen family members and bearing severe keloid scars on her face from the bombing, Ms. Kataoka initially lived a “quiet life”. For a long time, she, like many other Catholic survivors in Nagasaki, “had not spoken much.”

And yet, deep down, Ms. Kataoka struggled with Dr. Nagai’s interpretation of the bombing as “God’s providence.” She recalled wrestling with whether she should accept even her disfiguring scars as part of this divine plan, feeling that if it were so, then she “was not allowed to resent the atomic bombing.”

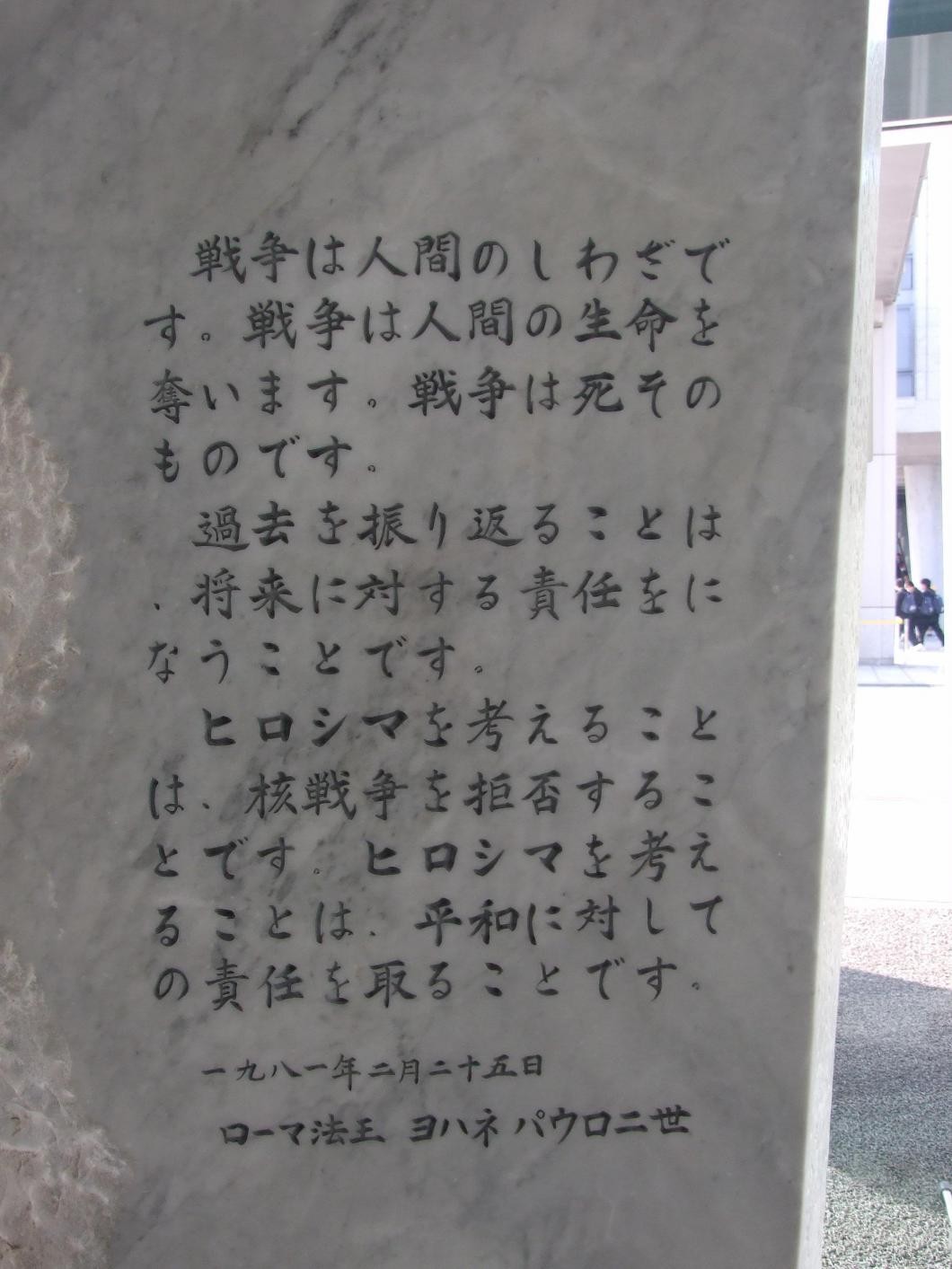

Then came a turning point. In 1981, Pope John Paul II visited Japan. During his peace appeal, he claimed that “War is the work of man“.

For Ms. Kataoka, it was a moment of revelation – of a profound shift in perspective. “When I heard Pope John Paul II say, ‘War is the work of man,’ I felt at ease,” she recounted. “I thought, ‘Ah, so that’s what it was.'”

To attribute war, and by extension the bombing, to “the work of man” rather than solely to “God’s providence” seemed to lift a weight. It reframed the tragedy not as something to be silently endured as a divine mystery, but as a consequence of human actions – and therefore, something that human beings have the responsibility, and the agency, to prevent from ever happening again.

This newly acquired sense of “ease” and clarity liberated Ms. Kataoka. She began to actively speak about her experiences, particularly to students on school trips, appealing for the abolition of nuclear weapons and world peace. “It was difficult for me to even be seen by others,” she recalled of her first attempts to speak, “but as I continued to talk, I completely forgot about the keloid scars on my face”.

Pope Peace Appeal Monument

(Translation: War is the work of man.

War takes human lives.

War is death itself.

To look back on the past is to take responsibility for the future.

To think about Hiroshima is to reject nuclear war.

To think about Hiroshima is to take responsibility for peace.)

(Image credit: dive-hiroshima.com)

And then, there’s the story of the late Ms. Chieko Watanabe. Despite being severely injured in the bombing and confined to a wheelchair, she “rose from the despair of the bombing to go on a ‘trip for peace’… to appeal for the abolition of nuclear weapons” both in Japan and internationally.

These stories make me think about how inner conviction, whether born of long-held faith or newfound understanding, can translate into such courageous outward action. They remind me of the human spirit’s capacity to redefine narratives, to find a voice even after being silenced by trauma, and to transform personal pain into a passionate plea for a better world.

When one’s “prayer” is fueled by a desire not just for individual solace – but for global peace, it becomes an active, evolving force, a wellspring for profound change.

The aspiration to be “the last”: Prayer as a vow

Beyond the individual transformations from silent suffering to vocal witness, there seems to be another powerful current running through Nagasaki’s collective spirit – a deeply held aspiration that their city will be the last to ever experience the devastation of an atomic bomb.

From what I can gather, it isn’t just a passive wish – but something akin to a sacred vow, a prayerful commitment shaping the city’s identity and its message to the world.

This fervent wish has found tangible expressions – one of which is the Oath Flame Lighthouse Construction Movement (誓いの火灯火台建設運動). According to Nagasaki City’s website, this initiative, born from the desire that “Nagasaki would be the last place to be hit by an atomic bomb,” led to the construction of a lighthouse in 1987, where an “Oath Flame” continues to be lit on the 9th of every month in Peace Park. In support of this movement, the singer-songwriter Kazumichi Terai even composed a song, “Burn, the Fire of Vows!” (Moero, Chikai no Hi!).

Another significant expression is the annual peace concert “From Nagasaki,” held by the renowned artist Masashi Sada. The concert has been held every year since 1987, poignantly on August 6th – the anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing – as an event “to send out peace from the atomic bomb site of Nagasaki.”

This choice of date feels particularly symbolic, a gesture of solidarity with Hiroshima, and a clear statement that Nagasaki’s prayer for peace extends beyond its own suffering, embracing the larger cause of “never again” for all humanity.

… Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays

As demonstrated in the activities above, the “prayer” of Nagasaki is not just a looking inward for solace, or upward for divine understanding – but also a looking forward, with a fierce resolve to shape a different future.

For my part, I feel that there is something really spiritual in a community that, having endured such an apocalypse, dedicates itself not just to remembering its sorrow, but to actively working and praying so that no other community will ever share its fate.

Seeing a whole community embody such a vow – to be a beacon of peace, to hold the line against future nuclear devastation, to maintain an unwavering commitment to the sanctity of life – is incredibly moving to me.

Weaving Threads: Anger, Prayer, and the Human Heart

As we’ve seen, the reality described in the expression “Hiroshima rages, Nagasaki prays” is far more nuanced than many may assume at first glance. These labels of “anger” and “prayer” are not absolute categories confining the experiences of an entire populace.

I recall learning from Nagasaki City’s website about the song “Peace from Nagasaki” by the group Peace Seven, which blended both “anger at the atomic bomb and a prayer for peace.” The song illustrates that these two seemingly opposite currents CAN and DO flow from the same wellspring of human experience.

Could it be, then, that Hiroshima’s “anger,” which I explored as a righteous fury against inhumanity and a fervent vow for “never again,” is also deeply intertwined with its own form of prayer – a desperate, sacred plea for humanity’s future? And that Nagasaki’s “prayer,” even in its most introspective or faith-based expressions, carries within it a powerful, if sometimes quieter, current of righteous indignation against the act that brought such suffering, and a determined resolve to ensure peace?

Despite the different primary notes that may resonate from each city’s story – the starkness of the preserved Dome versus the rebuilt Cathedral, the directness of some of Hiroshima’s poetic outcries versus the theological searching in Nagasaki’s Urakami district – the ultimate aspiration seems to be one and the same: a world free from nuclear weapons, a future where such devastation is never repeated.

The two cities’ paths of remembrance may have diverged in certain symbolic expressions, but the destination they strive for is surely a shared one.

In both cities, art – literature, music, memorialization – has served as such a vital channel for processing the unspeakable, for bearing witness, and for transmitting hope. Whether it’s the searing poetry of Toge Sankichi from Hiroshima or the soulful melodies and memoirs from Nagasaki, these expressions carry the weight of memory and the longing for peace across generations.

Perhaps this is where the labels begin to soften, revealing something more fundamental. In the face of ultimate inhumanity, the human spirit cries out. That cry might manifest as a roar of “anger,” a refusal to be silenced or to let the world forget. It might also take the form of deep “prayer,” a searching for meaning, solace, and a connection to something larger than the desolation.

But are these not, at their core, different facets of the same profound love for humanity, the same visceral rejection of its negation, the same desperate yearning for its preservation and flourishing?

It makes me reflect that beneath the surface of diverse cultural and historical expressions, the fundamental responses to profound loss and the deep-seated desire for peace are universal.

It’s in these depths, I believe, that we find our most essential, shared humanity.

Read more: Self-identity – A Contemplation on Being & Becoming

Hiroshima & Nagasaki: More alike than different

(Image credit: Wikimedia)

Personal Resonance: Lessons from the Ashes

Journeying through the narratives of Hiroshima’s “anger” and Nagasaki’s “prayer” has been more than an intellectual exercise; it has been a deeply stirring experience, one that has settled in my heart and continues to provoke thought and feeling.

One profound lesson I have realized is that we, as human beings, are capable of constructing meaning in the face of the unimaginable. The initial, almost stark, dichotomy of “anger” versus “prayer” felt too simple, and indeed, our exploration above has revealed a spectrum of responses far richer and more complex. As demonstrated through the individual narratives of those like Sankichi, Dr. Nagai, and Ms. Kataoka, history – especially traumatic history – is lived by individuals, each with a unique heartprint.

Reflecting on the two cities’ stories has also given me the opportunity to engage in deep contemplation of faith. As it turned out to me, faith is not a static set of answers, but a dynamic, living relationship – a space for questioning, for wrestling, for evolving, especially when confronted with the deepest mysteries of suffering and evil. In other words, it calls not just for solace or acceptance – but also for courage, justice, and active participation.

Whether one takes the “anger” or the “prayer” path, the important thing is to embrace a sense of humility and awe. Humility in the face of such immense suffering and the complex, deeply personal ways people navigate it. And awe at the enduring capacity for hope, for action, and for an unwavering commitment to peace that can rise from the ashes of utter devastation.

Read more: The World is Not Black and White – Finding Grace in the Grey

A Prayer and a Resolve for Our World

It has been decades since the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. And yet, the immense suffering it caused continues to hold profound implications for us all.

The above-mentioned stories of resilience, of faith tested and transformed, of anger channeled into peace, and of prayer blossoming into vows, all point towards an enduring truth: the human spirit, though capable of inflicting unimaginable horror, is also possessed of an even greater capacity for healing, for meaning-making, and for striving towards a better world.

The urgent, ongoing call for peace and the abolition of nuclear weapons, carried forward by survivors and advocates worldwide, feels more pressing than ever. It’s a call that transcends politics or ideology, touching the very core of our shared humanity.

And so, what remains for me is a simple, heartfelt prayer and a personal resolve.

A prayer for the souls who perished, for those who survived but bore unimaginable burdens, and for all who continue to suffer from the scourge of war and violence in our world today.

And a resolve, in my own seemingly trivial way, to carry the lessons of this reflection forward: to choose empathy over indifference, understanding over judgment, and to hold fast to the belief that peace, in our hearts and in our world, is not just a distant dream but a daily, conscious choice we can all make.

May we all learn to listen more deeply to the voices from the past, and in doing so, find the courage and wisdom to build a future where nobody ever again has to rage or pray through the ashes of such devastation!

I see therein the very challenge to join the minority. For the world is in a bad state, but everything will become still worse unless each of us does his best. So, let us be alert – alert in a twofold sense. Since Auschwitz we know what man is capable of. And since Hiroshima we know what is at stake.

Viktor E. Frankl, ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’

Other resources you might be interested in:

- Christian Existentialism: From Dogma to the Ultimate Reality

- 60 Existential Questions: A Daily Toolkit to Explore Life’s Depths

- Spiritual Purpose: The Quest for the Soul’s Calling

- 20 Japanese Philosophies of Life to Live by Everyday

- Silence Movie Review: A Meditation on Suffering, Doubt, and the Price of Belief

Let’s Tread the Path Together, Shall We?